Part of a series of articles titled Administrative History of the National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division.

Article

I&M Administrative History: The Stars Align

The author's copy of Preserving Nature in the National Parks. NPS photo.

The author's copy of Preserving Nature in the National Parks. NPS photo.Amid the maelstrom of bad publicity wrought by 1986’s Playing God in Yellowstone, National Park Service leaders had decided they needed someone to compile a detailed response to Alston Chase’s attack on NPS natural resource policy. They turned to NPS historian Harry Butowsky. When fellow NPS historian Richard Sellars heard Butowsky had been given just four months to complete the task, he decried it to his wife, Judy, as a “crazy idea.” Judy had a better one: Sellars should see if he could be assigned to the task, and given enough time to do a “credible, thorough job.” Sellars proposed the idea to his boss, Intermountain Regional Director John Cook. Cook liked the idea, agreed to give Sellars two years, and arranged to have the project reassigned. In retrospect, Sellars admitted he was “lying through my teeth” when he told Cook he thought two years would be enough.1 The project took nine years to complete. Published by a major academic press as Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History in 1997, the impact of Sellars’s work would make the book, itself, a part of history.

Anyone who imagined Sellars might paint a rosy picture of the bureau’s historical relationship with science, by virtue of being an NPS employee himself, would be proven wrong. Sellars believed in letting the documents speak for themselves, and he conducted the vast majority of his research in the National Archives rather than through interviews, piecing the story together from the words NPS officials had committed to history, rather than to memory. And the written record was clear: from the start, the NPS had prioritized visitor services and happiness over resource preservation, to the longtime detriment of the wildlife and wonders visitors came to see.

But unlike Chase, Sellars didn’t lay the blame squarely at the feet of the bureau’s resource managers and scientists. In his estimation, the group that had done more than any other to shape the NPS over the course of its history was not its rangers or, certainly, its scientists or resource managers. It was the bureau’s landscape architects—the people responsible for designing the built environment. Across the past eight decades, Sellars concluded, “Appearance was what mattered most.”

Sellars traced the influence of landscape architects back to the 1918 Lane Letter (authored by Horace Albright), which declared park development should be overseen by “trained engineers who either possess a knowledge of landscape architecture or have a proper appreciation of the esthetic value of park lands.” In keeping with Albright’s ideas about aesthetic conservation, in which a “complete” park landscape comprised a specific collection of scenic elements, park development was to proceed “in accordance with a preconceived plan” for each park, “with special reference to the preservation of the landscape.”2 This early emphasis on comprehensive planning as the organizing principle for shaping visitor experience, Sellars argued, cemented the central role of landscape architects in the bureau’s power structure—arguably reaching its zenith with the Mission 66 program led by Director Conrad Wirth (who had joined the NPS as a landscape architect in 1931), and the creation of the Denver Service Center (DSC) in 1972. Employing almost 800 landscape architects, architects, and engineers by the early 1990s, and with additional staff stationed in the field, the DSC was the servicewide locus of planning, design, and construction.

Across each management era—with the exception of the brief heyday of the Wildlife Division—Sellars exhaustively documented how, over and over, despite having a reputation as a worldwide leader in conservation, the NPS had failed to prioritize resource management and science in both budget allocation and park decisionmaking. The result was a powerful story of the bureau’s consistent, longstanding failure to embrace—let alone fulfill—its conservation mandate. “In both philosophy and management,” he wrote, “the National Park Service remains a house divided—pressured from within and without to become a more scientifically informed and ecologically aware manager of public lands, yet remaining profoundly loyal to its traditions.”3 Nine years of research led him to conclude that without a full embrace of science and a massive cultural shift, the bureau would continue to be just a pretender to the throne when it came to preservation:

It is essential that scientific knowledge form the foundation for any meaningful effort to preserve ecological resources. If the National Park Service is to fully shoulder this complex, challenging responsibility at last, it must conduct scientifically informed management that insists on ecological preservation as the highest of many worthy priorities. This priority must spring not merely from the concerns of specific individuals or groups within the Service, but from an institutionalized ethic that is reflected in full-faith support of all environmental laws, in appropriate natural resource policies and practices, in budget and staffing allocations, and in the organizational structures of parks and central offices. When—and only when—the National Park Service thoroughly attunes its own land management and organizational attitudes to ecological principles can it lay serious claim to leadership in the preservation of the natural environment.

It wasn’t just the bureau’s own reputation at stake. The fate of the nation’s greatest treasures hung in the balance.

In the past—as Chase and Sellars both pointed out—NPS leaders had often tried to discredit or ignore findings with which they disagreed, or that made the NPS look bad, or questioned its policies. Looking back in 2004, Robert Stanton, who was NPS director when Sellars’s book was published, recognized that in its wake, “One or two things could have occurred. I could have gone into denial saying that, ‘Well we are doing the best we can,’ and just happily float on down the river. Or I could say that Dr. Sellars has identified some areas in which we should be giving more attention.”4 Stanton chose the road less traveled by his predecessors. At a meeting of the NPS National Leadership Council at Key Largo in December 1997, at the urging of a handful of advisors, Stanton assigned Associate Director Mike Soukup to assemble a task force that would tackle the challenge outlined by Sellars. In time for fiscal year 2000, Stanton wanted a “strategy that will help institutionalize enhanced natural resource management capabilities in the Park Service.”5

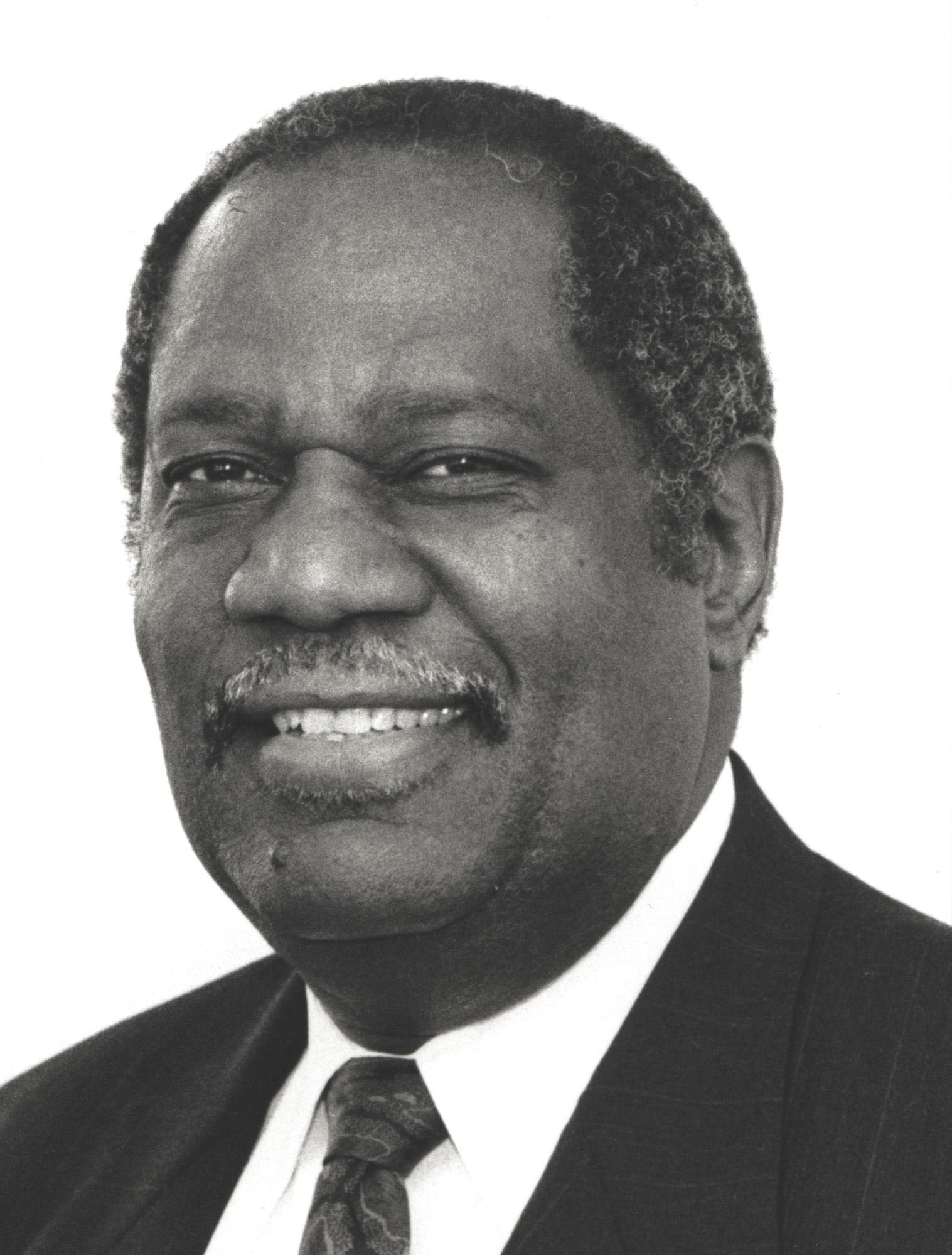

Robert Stanton, 15th director of the National Park Service. NPS photo.

Robert Stanton, 15th director of the National Park Service. NPS photo.Director Stanton had a reputation as a thinker who would listen, consider, and then support what seemed good and reasonable. But there were other reasons why it was not entirely surprising he would be the one to bring about a massive shift in priorities for the bureau. His directorship, itself, had been made possible by a leader who had looked at his agency, seen the need for fundamental change, and taken steps to do things differently than in the past. In 1961, in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall took note of his department’s lack of racial diversity and asked the leaders of his bureaus to give him an accounting of how many Black staff they employed. The National Park Service was found to have one Black ranger. In response to what he learned, Udall sent DOI recruiters to the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities. Stanton, a mathematics and chemistry student at Huston-Tillotson College in Austin, Texas, was invited to become a seasonal ranger at Grand Teton National Park. In a demonstration of the department’s commitment to the new rangers, his selection was confirmed in a letter from Udall, himself.

Stanton got a $250 loan to pay for his uniform and transportation from Fort Worth to Jackson Hole. His experiences as a young Black man in pre-Civil Rights Act rural Wyoming were mixed. But the professionalism of the Grand Teton staff opened his mind to the possibility of making his career with the NPS—which he did, from 1966 to his second retirement in 2001. Stanton rose through the ranks in administrative positions in Washington, DC. In 1970, he became the bureau’s first Black superintendent, in charge of the eastern National Capital parks. After another 26 years in leadership positions, Stanton retired—and then was brought back in 1997 to succeed Roger Kennedy as director.

Stanton was both the first Black NPS director and the first required to be confirmed by Congress. As part of an omnibus bill in 1996, Congress had amended the NPS Organic Act to specify that the president, rather than the Secretary of the Interior, would appoint the NPS director, making the position subject to Senate confirmation.6 This transfer of power from the secretary to the Senate was just one example of Congress’s increasing interest in NPS affairs during the 1990s, spurred on by the “Contract with America”—a Republican agenda rooted in the conviction that the federal government was “too big, too intrusive, and too easy with the public’s money.” The “contract” promised to reduce the size of government, lower taxes, slash welfare programs, and promote business interests. Before the end of the decade, Congress would wield its power of the purse to make an example of the NPS in more ways than one. Oddly enough, given Sellars’s narrative, they would do it by reining in the power of the landscape architects and elevating the stature of resource management and science.

In 1994, the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Interior and Related Agencies asked the General Accounting Office to investigate the workings of the Denver Service Center, which was suspected of being both a source of government waste and a sink for taxpayer dollars that would be better spent in the private sector. The GAO recommended some procedural improvements, but found that the DSC’s overhead costs were roughly in line with those of other government facilities, and park superintendents were generally satisfied in their dealings with its staff. Nevertheless, the House subcommittee continued to probe the center’s operations.

In 1996, an Inspector General’s report revealed that the DSC had, in recent years, overseen construction of park housing at Yosemite and Grand Canyon national parks that cost three times the amount of comparable built dwellings in the private sector. When it was further revealed that the DSC had spent $330,000 ($550,000 in 2021 dollars) to build a single composting outhouse with “a slate, gabled roof, cottage-style porches and a cobblestone foundation that can withstand an earthquake” at Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, the subcommittee ordered Secretary Babbitt to appoint an external committee to “review the construction practices of the Service, with primary emphasis on the role of the Denver Service Center.” A year later, the House Appropriations Committee sought to shift the DSC’s funding source from line-item construction to operations, with the goal of reducing its staff by half and moving the bulk of its duties to the private sector. Today, the DSC director supervises a staff of 250.7

Congress was also interested in how the NPS was handling resource management. And on both sides of the aisle, there was concern that management decisions were suffering from a lack of science. At a 1997 hearing of the House subcommittee on national parks, there was universal agreement on that point—though for different underlying reasons. In their testimony, speakers from the National Parks Conservation Association and National Research Council brought up the sheer number of reports and reviews that had urged reform of the NPS science program over the years, to little effect. NPS Director Roger Kennedy pointed out that Congress had given the bureau just a fraction of the funds the NPS had requested “to do inventory and monitoring to know what it is we have got that we are being berated for not knowing enough about.” In fact, in several fiscal years, Congress had decided funds requested for the Inventory & Monitoring program should be used to pay for unrequested construction, instead. Of ten expert witnesses who testified that day, six—including Kennedy—explicitly beseeched Congress to assign the NPS a scientific mandate.8

Of those who did not, a few spoke favorably of the work being done by the USGS-BRD to support the NPS. But the BRD was still a sore spot with some committee members annoyed that Secretary Babbitt had sidestepped them to create the National Biological Survey. Despite the overwhelming evidence that the NPS had a long history of scientific inadequacy, it was tempting to use its current problems as proof of Babbitt’s folly. In his opening statement, subcommittee chairman James Hansen (R-UT) framed the entire hearing as an opportunity to “examine the aftermath” of the reorganization. Entered into the record were the results of a survey indicating that NPS superintendents’ access to scientists and science useful for management had drastically decreased since the advent of the NBS.

As further evidence of the bureau’s lack of scientific access, Hansen observed the stunted progress of inventory and monitoring activities:

Only 86 parks have complete lists of animal species, only 11 parks have complete vegetation maps, and not a single major park has a comprehensive resource monitoring program. As a result, NPS cannot determine the health of the parks, can only sporadically address threats to park health, and park managers are not held accountable for the condition of resources they manage.9

Hansen also expressed concern about what would be the other major topic of the day: the purported power of superintendents to determine—and potentially suppress—research done in the parks. Though Alston Chase was not invoked during the hearing, some subcommittee members strongly concurred with his main points—that philosophy, not science, was guiding NPS management, and that park managers were often inclined to cherry-pick science that supported park policies and management goals, and squash science that did not. For this perspective, they called as witnesses Charles Kay, whose research on Yellowstone’s northern range was cited by Chase as evidence against the efficacy of natural regulation, and Richard Keigley, a USGS-BRD biologist also studying the northern range. Keigley testified that after his studies found the northern range was overgrazed (an indicator that natural regulation was not having its desired effects), park officials refused to consider renewing his research permit, effectively ending his work in the park. When Kay went so far as to accuse the NPS of censoring peer review at scientific journals, Idaho Representative Helen Chenoweth extrapolated the situation into the conclusion that “the park superintendent has total control over who does what research and ultimately who publishes what regarding the park.”10

Overgrazing on Yellowstone’s northern range had been a point of contention since the 1960s, when park managers had slaughtered thousands of elk over concerns the animals were exceeding the carrying capacity of the land. The ensuing controversy had been a motivating factor in the production of the Leopold Report, which had actually advocated continued manipulation of herd numbers—but also been the catalyst for the concept of natural regulation. By 1997, discussions of northern range carrying capacity had shifted from elk to bison. In recent years, increasing numbers of bison had migrated out of Yellowstone in winter, and into the State of Montana. Because some bison were known to be infected with brucellosis, concern that bison might transmit the disease to cattle, negatively impacting Montana’s livestock industry, had led to conflict between the park and the state government. In response, federal and state agencies began trapping bison near Yellowstone’s northern and western boundaries and sending them to slaughter. Bison that wandered outside the park were hazed back in or shot. During the particularly brutal winter of 1996, more than 1,000 animals were removed through management actions, and 400 more died inside the park. The situation was a public relations nightmare for everyone involved.11

Lakota Sioux spiritual leaders gather with park employees and community members at Stephens Creek, Yellowstone National Park, for a ceremony in honor of slain bison. March 6, 1997. NPS/Jim Peaco.

Lakota Sioux spiritual leaders gather with park employees and community members at Stephens Creek, Yellowstone National Park, for a ceremony in honor of slain bison. March 6, 1997. NPS/Jim Peaco.

The Congressional representatives of the park’s surrounding states (Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho) who sat on the House Resources Committee were convinced bison were leaving the park because they were starving. They were starving, the politicians argued, because park staff had failed to control their numbers as they pursued natural regulation, which Chase had deemed unscientific and Kay and Keigley found to be flawed.12 Natural regulation did have its defenders at the hearing, largely in the person of University of Wisconsin ecologist Mark Boyce, who had studied large mammals in the park for 20 years. But although science was politicized at the hearing, with some witnesses brought in to argue that NPS policy was scientifically unsound and others to support it, the credibility of science itself, as a truth-seeking endeavor, was universally embraced. Opinions converged on the idea that the NPS needed more science to make sound decisions.

There was also a palpable sense, among certain committee members, that park superintendents had too much power and too little accountability. After GAO Associate Director Barry Hill pointed out that Congress had appropriated funds specifically for resource information stewardship over the past five years, Representative Barbara Cubin (R-WY) asserted that “the money was not used in the way we had instructed it to be used.” Hill acknowledged that “We cannot track just to what extent” monies earmarked for resource stewardship were “actually going there and how much is being used for other demands that the park supervisor is facing on a daily basis.” His colleague, Cliff Fowler, explained that park superintendents were intentionally given broad discretion to decide how to spend their budgets to best meet park needs. When asked if the situation amounted to there being “350 little kingdoms going around the country without any accountability, neither to the Congress nor to the people,” Associate Director Hill demurred, “I would not call them kingdoms but I would certainly like to see like strength in accountability being exercised throughout the system.”13

In the end, most hearing participants seemed to agree that independent science was a means to better park management, and that better resource management was going to require more investment from Congress. Some also saw science as a means to rein in the power of park superintendents and policymakers who were too free to spend money as they pleased and manage the parks however they saw fit.

That was in February 1997. In September, Richard Sellars’s book was published. In early 1998, Associated Director Soukup’s Natural Resources Initiative (NRI) committee started putting together a plan to present to the NLC. It was a careful, deliberate process because they were aware that not everyone on the NLC shared the same priorities—and not even the committee members were always aligned in their thinking. After some false starts, they presented a plan to the NLC in September, feeling confident they’d get the support they needed to move forward. But the powerful Intermountain Regional Director John Cook—who had sponsored the writing of the history that inspired the initiative in the first place—raised serious, unexpected questions about both the plan and the amount of funding it called for. Cook was unconvinced that the elements proposed in the plan were enough of a priority to warrant the $200M it asked for, and concerned over a lack of detail about just how the funds would be spent.14

The NRI team went into the lunchtime break feeling battered and blindsided. But then, in an effort that has become the stuff of NPS legend, NPS Deputy Director for Operations Deny Galvin sat down with some of the group and told them he thought he understood what they were trying to do. He took out a pen and, on a napkin—or an envelope, depending on the storyteller—reduced the budget and sketched out a 12-point plan he thought could get funded:

- Protect Threatened & Endangered and native species

- Control exotics

- Practice environmental sponsorship (sustainable practices)

- Protect air quality

- Protect water resources

- Conduct natural resource inventories

- Conduct natural resource monitoring

- Improve Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit system

- Improve resource planning

- Use parks for science

- Use parks for learning

- Professionalize natural resource staff15

The group returned to the meeting, scrap paper in hand, and Galvin presented what he’d written down. The NLC liked what they heard. Point for point, that plan comprised what would become the Natural Resource Challenge (see Appendix D), a $100 million plan to overhaul the National Park Service’s natural resource management capabilities. If the $100 million was obtained, it would roughly double the funding available for natural resources management.16

But first, the task force had to convince the rest of the NPS that the initiative was worth getting behind. The fundamental goal was more than money. It was a paradigm shift comparable to the one George Wright had advocated in the 1930s: prioritizing resource protection over visitor convenience. And in that context, the speed with which the bureau had reverted to people-pleasing after George Wright’s death held an important lesson: lasting, systemic change could not be tied to the personal magnetism of a single, highly placed champion. To weather the inevitable tides of change at the leadership level, policy and practice had to be buoyed up by a groundswell of support from below.

Because the real NPS power base rested in its superintendents, demonstrating how the Challenge would benefit them was crucial. NRSS Deputy Assistant Director Abigail Miller and Washington Office detailee Robert Krumenaker, who were assigned to develop the 12 points and their budgets, formed a task group around each point, jointly led by a resource manager and a superintendent.17 Fortunately, two recent pieces of Congressional legislation had created needs the NRI was poised to fulfill.

With its goal of getting government agencies to shift their focus from individual activities to long-term results comparisons, the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) was, in concept, not unlike to the I&M program. GPRA required agency leaders to set broad goals, develop five-year plans with quantifiable objectives for meeting those goals, and then report the results for comparison from year to year. The goals had to be based on outcomes (results), rather than outputs (activities, products, or services). And they had to be “objective, quantifiable, and measurable,” to facilitate performance evaluation and personal accountability.18 In parks, the personally accountable person was the superintendent.

The National Park Service established four categories of servicewide goals: resource preservation, visitor enjoyment, enhanced resources and recreation, and organizational effectiveness. Each category was broken into multiple “mission goals.” Nested under those were quantifiable long-term goals to be achieved at the end of five years—for example, under resource preservation, “85% of Park units have unimpaired water quality,” and “19% of the 1999 identified park populations (84 of 442) of federally listed threatened and endangered species with critical habitat on park lands or requiring NPS recovery actions have improved status.”

More important for the I&M program, Mission Goal Ib stated, “The National Park Service contributes to knowledge about natural and cultural resources and their associated values; management decisions about resources and visitors are based on adequate scholarly and scientific information.” Quantifiable goals in this arena included completion of natural resource inventories for most parks, and identification of vital signs for monitoring at 80% of parks.19 To support the servicewide goals, each park produced a five-year strategic plan, with park-specific versions of the servicewide goals. To be able to prove they were meeting those goals, park superintendents would need someone to quantify their progress. With its focus on inventories, monitoring, protection of resources, and control of threats, the NRI promised to help do exactly that. Passed in 1993, GPRA was scheduled to go into effect in 1999.

The other law of consequence was the National Parks Omnibus Management Act (NPOMA), also known as the Thomas Bill. Though it wouldn’t become law until November 1998, NPS leaders were well aware of this legislation and its contents as the NRI effort got underway. Sponsored by Senator Craig Thomas (R-WY) with six Republican co-sponsors, NPOMA started out as a bill to reform NPS concessions policy. But given the kinds of concerns about superintendent overreach and a lack of scientific evidence for decisionmaking expressed at the 1997 House hearing on NPS science and resource management, it came to include a section intended to fundamentally alter the bureau’s decisionmaking process.

Wyoming senator Craig Thomas. Official portrait.

Wyoming senator Craig Thomas. Official portrait.Largely written by Associate Director Soukup and House Natural Resources Committee Steve Hodapp, with the support of Secretary’s Advisor T. Jestry Jarvis, Title II of the Thomas Bill had several purposes, all intended “to more effectively achieve the mission of the National Park Service.”20 Section 202 (Research Mandate) gave the NPS its long-awaited research mandate, directing the Secretary of the Interior to ensure that park management was “enhanced by the availability and utilization of a broad program of the highest quality science and information.” Section 204 (Inventory and Monitoring Program) provided a legislative mandate for inventory and monitoring, directing the Secretary to “undertake a program of inventory and monitoring of National Park System resources to establish baseline information and to provide information on the long-term trends in the condition of National Park System resources.” Section 206 (Integration of Study Results into Management Decisions) aimed to ensure that science was used in NPS decisionmaking, directing the Secretary to “take such measures as are necessary to assure the full and proper utilization of the results of scientific study for park management decisions,” and document the science considered when planning actions were expected to cause “significant adverse effects” to park resources. But perhaps most important for the NRI effort, Section 206 made trends in resource conditions “a significant factor in the annual performance evaluation of each superintendent.”21

Title II also directed the Secretary to partner with colleges and universities to establish cooperative study units (today’s Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Units) to conduct multi-disciplinary research and develop integrated information products on the resources of the National Park System, encouraged the use of parks for scientific study, authorized benefits-sharing agreements, and allowed for confidential protections of sensitive resource information. In its analysis of the Thomas Bill, the Congressional Budget Office confirmed that the NPS could perform the requirements of Title II under its existing budgetary authority—“assuming appropriation of the $160 million needed for that purpose over the next 10 years.”22

A big assumption. But also something the NRI could help with.

Though members of both political parties agreed that NPS managers needed more science, Title II was not without its detractors—the most prominent of whom was Secretary Babbitt. Still wary of anything that might undermine the USGS-BRD’s hold on scientific research in the Department of Interior, Babbitt expressed his displeasure with Title II to Senator Thomas, who was unsympathetic.23 Babbitt’s position was evident when, on June 5, 1998, Deny Galvin told the Senate that the park service, itself, opposed the title its staff had helped write:

We oppose the provisions of this title because we believe that it addresses issues which are adequately covered under existing authorities. The Department of the Interior has a single science agency, the US Geological Survey, which supports all of the Department’s bureaus. . . . the conduct of natural resource research is appropriately carried out by the USGS and the nation’s academic institutions.24

Galvin’s testimony dismissed the mandates for both research and servicewide inventory and monitoring as superfluous, arguing that the latter was unnecessary because the bureau had begun inventories and already had a handful of prototype monitoring programs, “developed in conjunction with the USGS.” The Senate was unmoved. The Thomas Bill became federal law on November 13, 1998.

Under GPRA, superintendents were now personally responsible for ensuring their parks were meeting quantifiable natural-resource goals. Under NPOMA, evaluation of their job performance was dependent on improving natural-resource trends. Suddenly, obtaining a consistent stream of knowledge about natural-resource conditions and trends was a priority for every superintendent, whether they wanted it or not. And on the back of that napkin (or envelope), Deny Galvin had outlined a plan for the Natural Resources Initiative that directly tied each of its 12 elements to an NPS GPRA goal, NPOMA’s Title II, or both (Appendix D). Though there would lingering worries from those who felt their programs and interests were being left out, the superintendents, whom Richard Sellars called “the most important locus of support” for the Natural Resources Initiative—and “the most influential group within the National Park Service,” had motivation to get on board.25

There were other positive signs. In an important departure from past efforts, the plan was also supported by many other key staff from outside the resource field, including Galvin and NPS comptroller Bruce Sheaffer.26 And as the 1990s came to a close, the future of the NPS was very much on Director Stanton’s mind. The imminent new millennium presented an unprecedented opportunity to focus the entire bureau on meeting the challenges it would bring. In December 1997, he asked the NLC to put together a servicewide conference for the year 2000. Instead of a superintendents’ conference, which was more typical, “Discovery 2000” would be a general conference of staff from the Washington office, regional offices, parks, and partners, in recognition that both the value of the parks and the hurdles they faced—climate change, shifting demographics, global species loss—were larger than the parks, themselves.27

The timing certainly seemed right to do something big in the name of helping secure an uncertain future—for park resources and for the world. So right that, as Associate Director Soukup recalled, the NRC’s originators mused that it might have been written in the stars. At that December 1997 Key Largo meeting, after Director Stanton had approved the creation of the NRI task force and announced Discovery 2000, the NLC had attended an evening boat ride on Florida Bay. “And I’ll swear, up in the sky, there were three planets aligned. We poked each other and said, ‘Hey, this is going to work.’ We were joking about it, but there was kind of a sense that things were pretty well aligned.”28

The Natural Resource Challenge represented the most significant commitment to science and resources in the history of the National Park Service.

The Natural Resource Challenge: The National Park Service’s Action Plan for Preserving Natural Resources (as the NRI came to be called), represented the most significant commitment to science and resources in the history of the National Park Service. It was also the strongest attempt ever made to institutionalize science-based management into the ethos of the bureau. In two introductory sentences, the document summarized the entire history of NPS ambivalence toward its conservation mandate and warned that given its current state of knowledge, the bureau had little hope of being able to navigate the 21st century. A nod to the Leopold Report helped drive home the point that the policies of the past were no match for the challenges ahead:

For most of the 20th century, we have practiced a curious combination of active management and passive acceptance of natural systems and processes, while becoming a superb visitor services agency. In the 21st century that management style clearly will be insufficient to save our natural resources. Parks are becoming increasingly crowded remnants of primitive America in a fragmented landscape, threatened by invasions of nonnative species, pollution from near and far, and incompatible uses of resources in and around parks.29

The plan consisted of 12 strategies, built around the 12 points Deputy Director Galvin had sketched out the previous year. To implement those strategies, it called for the creation of one new program (research learning centers) and the expansion of several others (I&M, Exotic Plant Management Teams, Air Resources, Water Resources, and Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Units). More significantly, the NRC provided a vision for reconceptualizing how the bureau would do business in the 21st century. In the document’s final section of “strategic approaches” was a blueprint for helping parks and programs to stop competing against one another for scarce resource dollars and start, in I&M parlance, “thinking like a network:”

The National Park Service will create networks of parks linked by geography and shared natural resource characteristics to facilitate collaboration, information sharing, and economies of scale in natural resource management. The National Park Service and collaborators in the networks will accomplish natural resource inventory needs and monitor park vital signs. . . . Each network of parks will provide a robust interface with other protected areas, people, and organizations in their common landscape. At least one private-public learning center will be developed in each network to facilitate the use of parks as libraries of knowledge and support visiting researchers. . . . [and] transfer information about park resources to park-based interpreters and the public at large. A university-based CESU associated with each group of parks will help NPS and other land managers protect, manage, and learn from the nation’s public lands.

It was an effort to get park superintendents and staff to start thinking of themselves at the macro scale—as part of a broader ecosystem of parks with common problems and solutions, rather than a collection of isolated fiefdoms destined to have to go it alone. It wasn’t financially feasible for each park to have its own I&M program, learning center, or CESU.30 Yet programs operated solely out of Washington, DC, had struggled to find relevancy with individual park managers. The network model offered parks the opportunity to share resources and jointly address problems whose scale was too large for any one park to handle on its own. Increasingly, these were the kinds of problems the 21st century appeared poised to present, as climate change and its attendant threats—drought, wildfire, invasive species, habitat shifts, flooding, none of which respected park boundaries—became the overriding focus of resource management concerns.

Though it didn’t purport to fix everything, the Natural Resource Challenge (in concert with NPOMA) was a specific, substantive response to more than seven decades of internal and external recommendations that the NPS should inventory and monitor its natural resources, encourage the use of parks for science (and science for parks), cultivate collaborative—rather than combative—relationships with outside researchers, use science as a basis for management actions, professionalize its resource staff, and increase funding for science and resource management.

One thing it did not do was suggest the NPS conduct “research,” so as not to draw the ire of Secretary Babbitt.31

By August 1999, each member of Director Stanton’s National Leadership Council had signed the final NRC document. This was unusual. Stanton could have just signed it himself, perhaps with a signature of support from the Interior Secretary, as Director Mott had done with his 12-point plan in 1985. But Stanton wanted a display of unanimity that would leave no room for doubt that the entire bureau was fully committed to the principles and actions outlined in the Challenge.32 The crowded signature page demonstrated that this was no one-man crusade. It was a statement of where the NPS was headed—springing not from “specific individuals within the Service,” as Sellars had warned against, but meant to represent an institutionalized embrace of a cultural shift.

Signatories to the Natural Resource Challenge during a meeting at Jackson Lake Lodge, Grand Teton National Park, in 1998. Clockwise from back left: Jerry Belson (Southeast Regional Director), Mike Soukup (Associate Director, Natural Resources and Science), Bill Schenk (Midwest Regional Director), Terry Carlstrom (National Capital Regional Director), Robert Stanton (Director), Deny Galvin (Deputy Director), Kate Stevenson (Associate Director, Cultural Resource Stewardship and Partnerships), Sue Masica (Associate Director, Administration), Bob Barbee (Alaska Regional Director), Maureen Finnerty (Associate Director, Park Operations and Education), Marie Rust (Northeast Regional Director), John Reynolds (Pacific West Regional Director), Jackie Lowey (Deputy Director), Ron Everhart (Intermountain Deputy Regional Director, standing in for signatory John Cook, Intermountain Region Director). Not pictured is signatory Bruce Sheaffer (Acting Associate Director, Professional Services). NPS photo.

Signatories to the Natural Resource Challenge during a meeting at Jackson Lake Lodge, Grand Teton National Park, in 1998. Clockwise from back left: Jerry Belson (Southeast Regional Director), Mike Soukup (Associate Director, Natural Resources and Science), Bill Schenk (Midwest Regional Director), Terry Carlstrom (National Capital Regional Director), Robert Stanton (Director), Deny Galvin (Deputy Director), Kate Stevenson (Associate Director, Cultural Resource Stewardship and Partnerships), Sue Masica (Associate Director, Administration), Bob Barbee (Alaska Regional Director), Maureen Finnerty (Associate Director, Park Operations and Education), Marie Rust (Northeast Regional Director), John Reynolds (Pacific West Regional Director), Jackie Lowey (Deputy Director), Ron Everhart (Intermountain Deputy Regional Director, standing in for signatory John Cook, Intermountain Region Director). Not pictured is signatory Bruce Sheaffer (Acting Associate Director, Professional Services). NPS photo.Stanton unveiled the Natural Resource Challenge on August 12, 1999, at the centennial celebration for Mt. Rainier National Park. By that time, nearly $20 million in initial funding for the Challenge had already been included in President Clinton’s FY2000 budget, for natural resource inventories, exotic species control, and large-scale preservation and restoration projects.33 Of course, the President’s budget is one thing. Getting Congress to actually appropriate the requested funds is entirely another. But in this instance, NPS leaders felt good about their chances. For one thing, NPOMA had enjoyed bipartisan support in both houses of Congress. Moreover, discussions with influential Congressional appropriations staffpeople had convinced NPS leaders they had a good shot at getting what they wanted. As Mike Soukup recalled,

We had a chance to brief them, and we told them what we thought needed to be done, and they said, “Whoa, where have you been? We’ve been expecting something besides a maintenance backlog and law enforcement to come forward sooner or later, because you guys [have] got to know what you’re doing!” So they were very surprised and impressed that they got a chance to look at some actual biodiversity protection.34

Those sentiments were reflected in the budget section of the NRC document, which noted that while just 7.5% of the FY1999 NPS budget and less than 5% of the bureau’s permanent staff were devoted to resource management, the last 20 years had seen three major investments in park facilities—including one worth $1 billion. The NRC sought a total base funding increase of 1/10 that amount, to be phased in over five years. For FY2000, Congress appropriated a $14,329,000 initial investment in the Natural Resource Challenge.35 The stars had indeed aligned.

Fiscal year 2002 brought a change in presidential administrations (and another $3 billion dedicated to backlog maintenance). Ultimately, NRC appropriations fell short of the full $100 million, but enough support remained to bring the total funding increase to $77.5 million.36 The I&M program was the cornerstone of the NRC, directly receiving about 53% of Challenge funds and, to a large degree, serving as its organizational foundation.37 To assuage Congressional—and NPS—concerns that park superintendents or other entities might re-direct NRC monies to other purposes, the bureau was required to produce an annual Report to Congress detailing how the funds were spent. Though the NRC was considered “completed” in FY2007, the report was produced for each fiscal year from 2000 to 2011.38 This unusual level of transparency and accountability was also likely a preventive antidote to the kinds of fiscal bombshells that had turned the woes of the DSC into national news.

The Natural Resource Challenge, designed to help the National Park Service successfully meet the future, began with a story of its past. Published at a time when Congress was united in its support for science as cure for the park service’s ills, Preserving Nature in the National Parks was the NRC’s “catalyst for action”39—a compelling, comprehensive, credible narrative that documented the bureau’s failings and laid a clear path to redemption. The book placed NPS leaders at a crossroads: continue down the comfortable road of failure, or do everything in their power to change course. Buoyed by skilled leaders, a director who was open and committed to change, favorable legislation, millennial preoccupation, and superintendent support, the Natural Resource Challenge was a visionary plan that offered practical, targeted solutions to both short- and long-term problems. The NPS now had a framework for making science a pillar of park management, and the money to start implementing it. If the pressure to make the Challenge a reality had been formidable, then the pressure to make it succeed was staggering.

NEXT CHAPTER >>

<< PREVIOUS CHAPTER

Research and writing by Alice Wondrak Biel,National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division

1Richard West Sellars, interview by Lu Ann Jones, November 7, 2014, http://npshistory.com/publications/sellars/interview.pdf.

2Lane to Mather, “Secretary Lane’s Letter on National Park Management,” May 13, 1918; Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 52.

3Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 290.

4Robert G. Stanton, Oral History Interview with Robert G. Stanton: Director, National Park Service, 1997-2001, interview by Janet McDonnell (National Park Service, 2006), 42, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/director/stanton.pdf.

5“Summary, NPS National I&M Advisory Committee Meeting, Jacksonville, Florida”; Richard West Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 292. In 1997, the National Leadership Council was composed of the Director, Deputy Directors, Associate Directors and Regional Directors. The group met quarterly to consult on major policy and program issues confronting the NPS.

6“Omnibus Parks and Public Lands Management Act of 1996,” Pub. L. No. 104–333 (1996), https://www.congress.gov/bill/104th-congress/house-bill/4236/text.

7US General Accounting Office, “Views on the Denver Service Center and Information on Related Construction Activities,” June 1995, https://www.gao.gov/assets/230/221332.pdf; Hon. Ralph Regula, “H. Rept. 105-337 - Making Appropriations for the Department of the Interior and Related Agencies, for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1998, and for Other Purposes” (House of Representatives, 105th Congress, 1st Session, October 22, 1997), https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/105th-congress/house-report/337; Stephen Barr, “$330,000 Outhouse? Hill Critics View It as a Matter of Waste,” Washington Post, October 30, 1997, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1997/10/30/330000-outhouse-hill-critics-view-it-as-a-matter-of-waste/84cf0ae3-5ded-4238-ac48-a92d2b801b42/. Regula, “H. Rept. 105-337 - Making Appropriations for the Department of the Interior and Related Agencies, for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1998, and for Other Purposes.” National Park Service, “Office of the DSC Director,” Denver Service Center, May 14, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1804/dscdirector.htm.

8“Science and Resources Management in the National Park Service.”

9“Science and Resources Management in the National Park Service,” 2.

10“Science and Resources Management in the National Park Service,” 50.

11Douglas W. Smith et al., “Wolf–Bison Interactions in Yellowstone National Park,” Journal of Mammalogy 81, no. 4 (November 2000): 1128–1135.

12Montana Representative Rick Hill decried natural regulation as “voodoo environmentalism” and, raising the spectre of the 1988 Yellowstone fires, declared that the park’s “let-it-burn” policy was being repeated as a “let-them-starve” policy. Science and Resources Management in the National Park Service, 4.

13Science and Resources Management in the National Park Service, 16.

14Soukup, interview by Biel and Beer, December 10, 2019; “November 17, 1998 Meeting” (NPS National I&M Advisory Committee Meeting, Springfield, Missouri, 1998).

15“November 17, 1998 Meeting”; Soukup, interview by Biel and Beer, December 10, 2019; Davis, interview by Biel and Beer; Michael Soukup to Alice Wondrak Biel, “Re: Review an Article?,” July 15, 2022.

16Soukup, interview by Biel and Beer, December 10, 2019; Davis, interview by Biel and Beer; National Park Service, “Natural Resource Challenge: The National Park Service’s Action Plan for Preserving Natural Resources” (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science, Washington, D.C., August 1999), http://npshistory.com/publications/natural-resource-challenge.pdf.

17Sherry A. Middlemis-Brown, “History and Development of the Heartland Inventory and Monitoring Network,” Natural Resource Report (Fort Collins, Colorado: National Park Service, 2016), 6.

18Yellowstone National Park, “Yellowstone National Park Strategic Plan (FY 2001-2005),” March 20, 2000, 1, https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/management/upload/strategicplan.pdf.

19Yellowstone National Park, "Yellowstone National Park Strategic Plan," 47.

20National Parks Omnibus Management Act of 1998.

21Title II also directed the Secretary to partner with colleges and universities to establish Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Units to conduct multi-disciplinary research and develop integrated information products on the resources of the National Park System, encouraged the use of parks for scientific study, authorized benefits-sharing agreements, and allowed for confidential protections of sensitive resource information.

22Congressional Budget Office, “Congressional Budget Office Cost Estimate: S. 1693, Vision 2020 National Park Service Restoration Act,” June 23, 1998, 6, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/105th-congress-1997-1998/costestimate/s169330.pdf.

23Soukup, interview by Biel, June 3, 2021.

24“Senate Report Accompanying S. 1693, Vision 2020 National Parks Restoration Act,” June 5, 1998, https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/105th-congress/senate-report/202/1.

25Soukup, interview by Biel, June 3, 2021; Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History, 293. The power of superintendents to make a program sink or swim is evident in a set of IMAC meeting notes from November 1998, which contain speculation that the “crash” of the DSC was set in motion after superintendents had begun complaining about it to their Congresspeople—and that I&M funding had been cut by 5% in FY1999 (after increasing 111% from FY96 to FY98) after similar complaints from superintendents reached Congress. “November 17, 1998 Meeting.”

26Abigail Miller to Michael Soukup, “Re: NRC Piece,” July 5, 2022.

27McDonnell, “The National Park Service Looks Toward the 21st Century.” The conference’s five days were focused on four themes: education, leadership, and natural and cultural resource stewardship. In the symbolic shadow of St. Louis’s Gateway Arch, Stanton asked more than 1,200 conference participants to “contemplate a vision—to dream, anticipate, and begin to formulate the role the National Park Service will play in the future of this nation.” The next day, biologist E.O. Wilson exhorted the increasing value of the national parks as sites for the preservation of biodiversity in a world where it was swiftly shrinking—and for scientific research, education, and the very “future of society.”

28Soukup, interview by Biel and Beer, December 10, 2019.

29National Park Service, “Natural Resource Challenge: The National Park Service’s Action Plan for Preserving Natural Resources.”

30Michael Soukup to Regional Directors, Pacific West, Southeast, Intermountain Regions, “Decisions on the Allocation of Prototype Monitoring Funds,” February 7, 2000, Folder, Vital Signs Network Sequence, Inventory & Monitoring Division, Ft. Collins, Colorado.

31Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks (2009), 294.

32Stanton, Oral History Interview by Robert G. Stanton: Director, National Park Service, 1997–2001, 43.

33National Park Service, “Natural Resource Challenge Original Press Release,” August 12, 1999, https://www.nps.gov/nature/pressrelease.htm.

34Soukup, interview by Biel and Beer, December 10, 2019.

35National Park Service, “Natural Resource Challenge Funding The National Park Service’s Action Plan for Preserving Natural Resources: A Report to the United States Congress Fiscal Year 2000” (Washington, DC: Natural Resource Stewardship and Science, July 2001).

36Michael A. Soukup and Gary E. Machlis, American Covenant: National Parks, Their Promise, and Their Future (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021), 150; Soukup, interview by Biel, June 3, 2021. National Park Service, “Funding the Natural Resource Challenge: FY 2009 Report to Congress,” 2010, 4. National Park Service, “Funding the Natural Resource Challenge: Report to Congress, Fiscal Year 2008,” 2009, 9.

37Steven G. Fancy to Alice Wondrak Biel, “NRC Funding for I&M,” June 10, 2021; National Park Service, “Report to Congress 2008,” 99.

38National Park Service, “Report to Congress 2008,” 9.

39Abigail Miller and Douglas K. Morris, “Natural Resource Challenge Addresses Natural Resource Protection Needs,” Natural Resource Year in Review--1999, August 2000, 1–2.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tags

Last updated: September 25, 2023