Last updated: November 22, 2021

Article

History of the Ohio & Erie Canal

NPS Collection

The Ohio & Erie Canal traveled through the Cuyahoga Valley on its way to connecting the Ohio River with Lake Erie. Wherever this man-made ditch went, change followed: change for the Cuyahoga Valley, the region, and the nation. In the wake of the canal came prosperity, a national transportation system, and a national market economy.

Connecting the Frontier and the Nation

In the early 1800s, most of the United States was frontier, sparsely settled by independent Indian nations and wandering explorers. Many European settlers came west to places like the Cuyahoga Valley seeking rich land to farm. Once here, most settlers struggled just to be self-sufficient. Even if they could raise a crop, getting surplus to markets required a journey of more than a month. The prices paid for these goods hardly made the journey worthwhile.

The United States was still new: a young nation founded on democracy with vast undeveloped resources. In the East, the economy depended on imports from Europe. The West had no efficient way to export goods over the Appalachian Mountains. This growing nation focused its energy on “internal improvements.”

NPS

Building the National Transportation System

The first step towards uniting a country divided by geography began in 1817 with construction of the Erie Canal. This canal linked New York’s Hudson River with Lake Erie at Buffalo. The Erie Canal opened in 1825, immediately benefiting New York and beyond.

The Erie Canal was the beginning of a national transportation system, connecting ports on the Great Lakes with eastern markets. To reach into the Midwest, America needed canals built farther inland. Seeing the benefits of the Erie Canal, Ohio caught canal fever. By 1825, plans to link Lake Erie with the Ohio River were underway. Many routes were under consideration, but a continental divide in northern Ohio created a major obstacle. Geography and politics both affected decisions about the canal’s route. At the divide’s highest point, today’s Summit County, the canal would need additional sources of water. The Cuyahoga River and the nearby Portage Lakes could supply that water.

When Simon Perkins offered land in what is now Akron, the state decided to route the canal through the Cuyahoga Valley. Power and money motivated land owners, such as Peninsula’s Herman Bronson, who offered free land to the state—if the canal would pass through their property. Using design specifications from the Erie Canal, construction on the Ohio & Erie Canal began throughout the state in 1825. It took two years of hand digging to complete the section from Cleveland to Akron, and five more years to finish all the sections. Dug largely by Irish and German immigrants, this four-foot-deep ditch stretched 308 miles to Portsmouth on the Ohio River. By the fall of 1832, the canal promised passage from Cleveland to Cincinnati in 80 hours, a trip that had once taken weeks.

NPS Collection

Changes Brought by the Canal

Records indicate immediate profits from the canal. Prior to the completion of the Ohio & Erie Canal, Cleveland merchants shipped 1,000 barrels of flour to Buffalo for transport to eastern markets, sometimes for as low as $0.10/ barrel. Six years later, 250,000 barrels of flour, flowed through Cleveland, headed east to places like New York City. Cheaper than imported European grain, American-grown grain often sold for as high as $1/barrel.

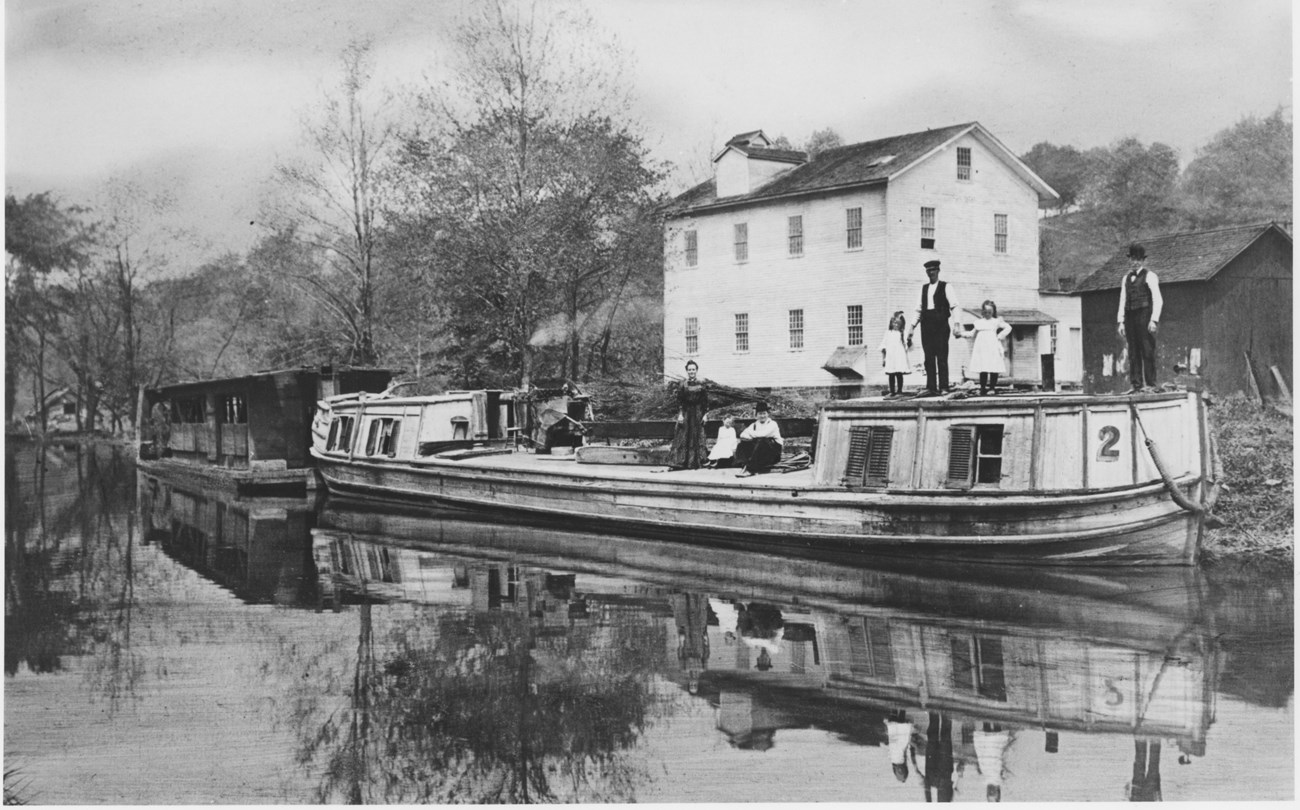

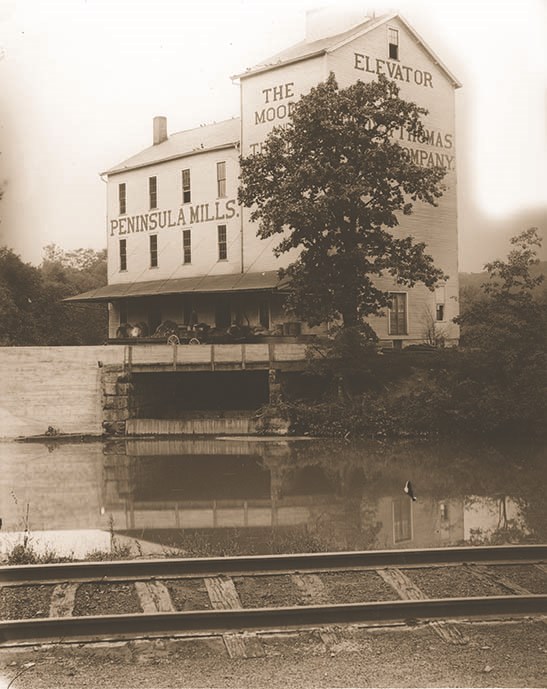

Other businesses began to grow and flourish along the canal. In the Cuyahoga Valley, mills—such as Alexander’s Mill in today’s Valley View and the Moody and Thomas Mill in Peninsula—were soon grinding grain to ship eastward. People built stores and taverns to fill the needs of the farmers and canal travelers. A local example was Moses and Polly Gleeson's tavern at Lock 38, now Canal Exploration Center.

Iron ore, coal, oats, pork, lard, cheese, salt, wool, and even whiskey joined the exports to the East. As more land was cleared for farming, people also began shipping excess timber. Increasing prosperity meant eastern markets shipped more goods west. These included American-made cotton fabric and imported coffee, tea, sugar, and china. As transportation costs dropped, these goods became more affordable.

The canal brought other, more subtle changes. These included changes in foodways and in perceptions. New foods, such as salertus (baking powder), were imported, which made use of new technology—the cook stove and Ohio-made cast ironware. Recipes, fashion, news, and ideas now traveled at unheard of rates. Where information had taken 30 days to arrive in Ohio from New York, it now took a mere 10 days.

Cities boomed wherever the canal went. During the first decade, property values all along the canal increased, sometimes as much as 360% from pre-canal days. As people moved to Ohio, the canals provided the nation with mobility. By 1850, due largely to the canal and the people it brought, Ohio was the third most populated state. The Ohio & Erie Canal opened up Ohio and expanded America’s market economy. Americans were able to buy and sell more basic goods with each other, lessening their dependence on foreign imports. Ohio’s canal system helped set the stage for the young country to become a formidable player in the world economy.

NPS / Tim Fenner

The Modern Canal

The Flood of 1913 damaged the canal, making it too expensive to repair. Afterwards, some use of the canal continued. For example, a steel mill in Cleveland purchased the canal water for industrial purposes and keeps water in a section north of State Route 82. Realizing the history and scenic values of the canal and its surroundings, in the 1970s citizens began to campaign for their preservation. The Ohio & Erie Canal became the spine of Cuyahoga Valley National Park, established in 1974. In 1996, it also became the backbone of the new Ohio & Erie Canalway. This national heritage area continues to improve life here in Northeast Ohio. The canal no longer carries goods, news, or people. Instead, its adjacent Towpath Trail transports hikers, cyclists, and horse riders. Today, the Ohio & Erie Canal leaves change in its wake, providing people in urban areas with green spaces for recreation and enjoyment.