Last updated: March 21, 2023

Article

Paul Murphy Remembers the 1913 Flood

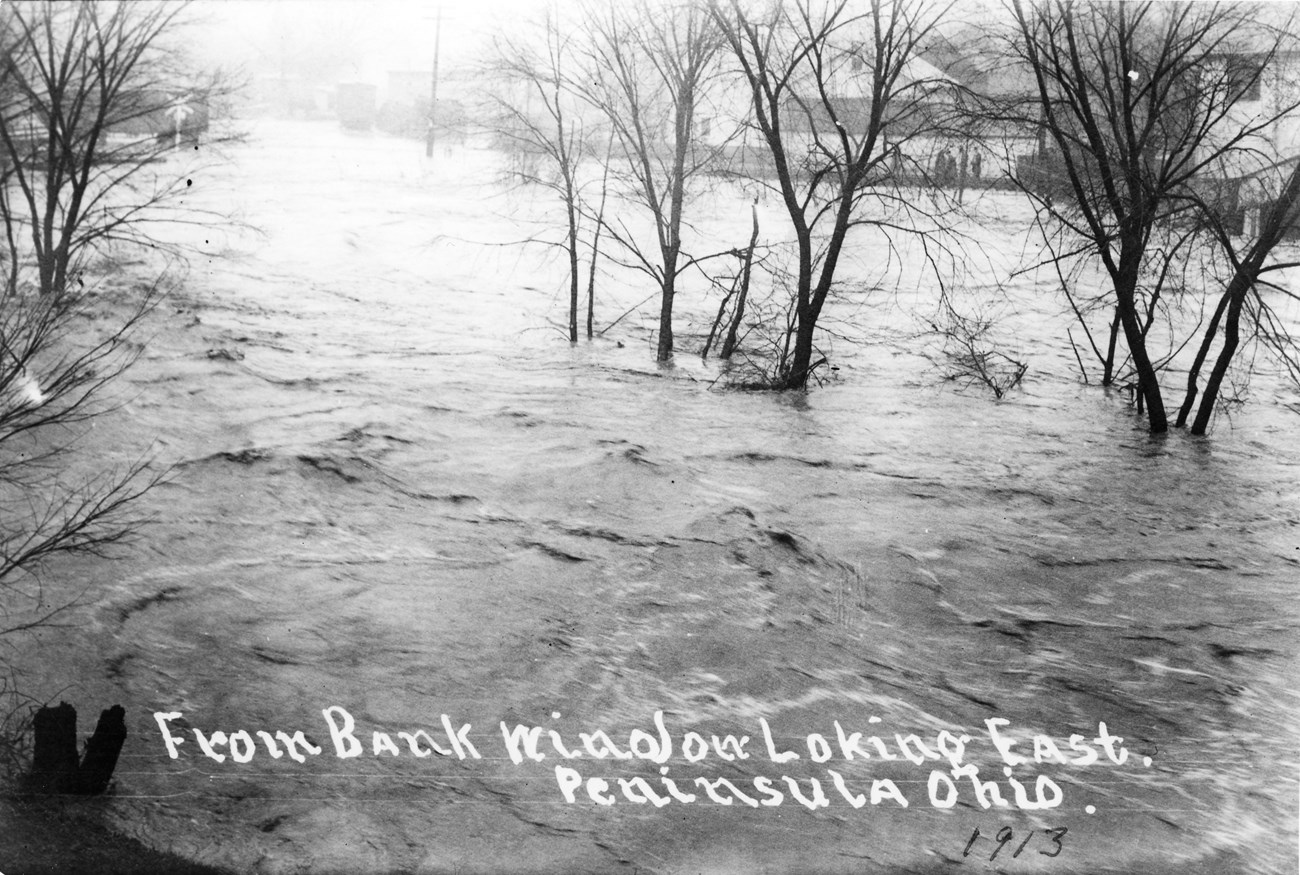

NPS Collection / G.N. Damon & Daughter

From March 23-27, the Great Flood of 1913 swept over 17 states, hitting Ohio the hardest. Violent storms had begun the week before in parts of the Midwest. The frozen ground could not absorb the deluge of water. Every river in the state swelled out of its banks. Nationally, at least 600 people lost their lives and a quarter million became homeless. Buildings, utilities, roads, bridges, railways, and dams were washed away. The widespread damage spelled the end of the Ohio & Erie Canal.

The Murphy family lived on a Cuyahoga Valley farm along the canal at Lock 35, just south of Station Road Bridge. In the following essay, their son Paul described his boyhood memories of this dramatic event. His descendants shared this firsthand account with the national park during a visit in 2011.

Paul Murphy Family

Rocky Mountain Jack: A True Experience by Paul Ervin Murphy

It was the Spring of 1913 … at Easter time, to be exact!

On the little farm in the Cuyahoga Valley of Ohio, we were all looking forward to the Easter season and, as a boy of seven, I enjoyed helping my mother color the traditional Easter eggs.

This year was to be special because my maternal grandparents were coming out from Cleveland to be with us. They arrived on the five o’clock train on Thursday and I remember running joyfully down the narrow dirt road to meet them.

In the brown suitcases they were carrying, I was sure there would be boxes of marshmallow chicks and chocolate bunnies. They never disappointed me!

A dark and ominous cloud bank had obscured the setting sun that evening, but no one gave it much thought because spring showers at Easter time were by no means unusual.

Suddenly … as we were all sitting around the dinner table, a deluge of heavy rain plummeted down on the shingle roof. We all looked at each other and someone remarked that a sudden heavy shower never lasts too long … and … we went back to our evening meal.

Half an hour later there was no let-up to the downpour, and my father and Dave Boam went out to the barn to make sure all the livestock were safe and secure.

Dave was a Civil War Army buddy of my father who lived with us and helped out on the farm. They soon came stomping back to the front porch … shed their dripping rain gear and came in to say that everything was safe at the barn.

Dave also said that a few more hours of this heavy rain would bring the river out of its banks. But, since this was a yearly occurrence, we gave it little consideration.

We tried to keep our conversation light and cheerful that evening, but our best efforts were dampened by the steady downpour. Realizing that there was little else to be done that night, we retired … wishing each other a good night’s sleep. My room was upstairs and, in spite of the thunderous rain, [I] was soon sound asleep.

I woke early the next morning and went immediately to the window. As had been predicted, the river was already out of its banks and I could see driftwood and other debris floating down with the current. The rain had eased a little and I hoped it would soon stop altogether.

The rest of the family was already gathered in the kitchen where my mother, grandmother, and my Aunt Ellen were busy preparing breakfast.

They smiled, when I remarked that it was not raining quite as hard as it had during the night, but I am sure they were not completely convinced.

The men had already completed the morning chores and I heard the whir of the milk separator which divided the cream from the skim milk. The cream was churned into butter; the skim milk was fed mostly to the hogs.

Looking out the kitchen window, I saw that one of the men, probably Dave, had driven a tall wooden stake into the pasture ground at the very edge of the flooded area. We could use this as a landmark to gauge how rapidly the water was rising.

Very little farm work could be done, other than the daily cleaning of the stables and the gathering of eggs from the chicken coops.

Our black Minorca rooster, which Dave had named Rocky Mountain Jack, took a very dim view of remaining in the coop and expressed his displeasure in no uncertain terms!

As the day wore on and the rain continued to hammer incessantly on the shingle roof, everyone became apprehensive and finally … tentative plans for a possible evacuation were discussed. Some friends of ours had a small cottage at the top of the wooded hill about five hundred feet higher than our farm. We kept a key to this cottage, looking after it during their absence. This then was an obvious place of refuge in case of emergency.

To reach high ground, we had a metal-bottomed flat boat and also a canoe, which we kept on a small knoll along the bank of the Ohio [& Erie] Canal. This canal was about fifty feet in front of the house: the Cuyahoga River approximately two hundred yards to the rear. During hard rains these both received tremendous runoff water from various creeks and valleys upstream from our small farm.

Directly across from us was a beautiful scenic gorge with a creek called Rock Run. When at infrequent intervals the heavy rain eased for a few minutes, we could hear the angry roar of Rock Run and see the flood spilling over the banks into the canal. With the canal rising in front … and the river swirling toward us from the rear, we felt evacuation was inevitable!

That evening the flood water began to fill the cellar under the house. We could hear various floating things bumping around and my grandfather, trying to inject a little humor into the situation, said that he could hear the rats leaving!

Mother brought in a large laundry basket and filled it with food enough to last several days. Additional containers held our spare clothing and other necessities. Some of our furniture had been carried upstairs, along with other perishable things.

A good nourishing dinner was prepared that night and we were told to eat plenty to build up our strength. None of us slept very well after we retired. It seemed as though my head had scarcely touched the pillow when my mother was telling me to hurry and get dressed.

As I sleepily complied, I heard the old kitchen clock striking the ungodly hour of 3 a.m.

In spite of all the stress we felt, mother served a substantial breakfast and even insisted that the dishes be done. The men went out to the barn and, in the dismal light of dawn, [I] saw them lead the livestock out of the barn—which already had water up to the bellies of the animals!

All the chickens were carried to the house and placed in the coal shed, where they would be reasonably safe.

Rocky Mountain Jack, however, took a dim view of being put into the shed. He somehow escaped from the men and flew to the big haystack. A neighbor told us later when the haystack was carried away by the flood, the proud black Minorca, rode on top of the hay, disdainfully crowing at the impending danger. We never saw him again!

With all the livestock freed, the men came in for a final change of dry clothes. They had been wet and cold for several hours. At this point, the water was up to the front porch and we could no longer postpone our departure.

My brother brought the flatboat and canoe up to the porch. We loaded all the food and other things into the boat [and] then we ourselves climbed in.

I will never forget that boat ride! Our dog assumed a position in the prow of the boat, like Washington crossing the Delaware.

Once inside the neat little cottage, we rapidly set about making the best of a crowded situation. During meals most of us had to hold our plates on our laps; the table would only accommodate four. There was only one small bedroom—which of course my grandparents occupied—so at night the main floor had wall-to-wall people!

The men had gone back to the farmhouse but there was nothing to be done, but watch. By nightfall, there was over a foot of water in the house and, although the rain had slackened some, the crest of the flood was still rising.

The next morning the rain had stopped and the errant sun looked down on a desolate valley, still flooded from one side to the other.

All train traffic had been suspended on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad [now Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad], which ran between Cleveland and Akron. Several days were necessary to repair the flood damage to the tracks.

Josh Wright, our nearest neighbor, came to see how we were doing. It seems our cows had come to his barn wanting to be fed and milked. Josh was a very fine neighbor and friend who lived about half a mile from the cottage.

He offered to take my grandparents to the Inter-urban Car Station in Northfield, where they caught a streetcar back to Cleveland.

He also took care of the cows until we could bring them home! The horses and pigs had found refuge on high ground and returned, pretty much on their own after the flood subsided—especially when enticed by tempting food.

I believe the river that year crested nearly twenty feet! It was a week before the water was low enough to allow us to enter our house. Mud was six inches deep on the floor! All the wallpaper was ruined! The rag carpeting in the living room had to be taken apart in three-foot strips [and] hung out on the clothesline to be washed by hand and dried in the sun—later to be assembled and tacked down to the floor.

Things in the cellar were a complete mess. All the labels had been soaked off the jars of fruits and vegetables. Our pork barrel was a complete loss. The potatoes had to be dug out of the mud and salvaged, where possible. It was several weeks before we could do anything much in the cellar.

We cleaned out the barn and found that the hay in the loft was dry and usable. The chicken coop had to be rebuilt. The corn crib was shaky but intact.

The outhouse had floated a mile or so downstream [and] had lodged in a clump of trees, waiting for us to reclaim. Much of the pasture fence was damaged and had to be restrung. The pasture, itself, was a long time returning to normal. We had to dry-feed the livestock for quite a long while.

In addition to the emotional shock which we all suffered, my father and Dave developed pneumonia and were ill for quite a long period of time. Dave never did fully recover and died that following September.

During the several remaining years that we lived on the farm, whenever there was a damp rainy period, the musty smell left by the flood residue was very noticeable in the house. No amount of cleaning and fumigating was effective in eliminating that odor!

The Ohio [& Erie] Canal had been put through in 1832. Our farm house, barn, and corn crib were built shortly thereafter. The house and barn were of single constructions with hewn timbers fitted with dowel pins, instead of with nails. The only heat upstairs was from the stovepipe which ran up through the floor and out through the roof.

In the winter, snow would drift through the cracks in the wall and form a small mound on my bed! This farmhouse, where I was born in 1905, had no electricity! It had no running water, no modern conveniences! It was heated by a pot-bellied coal stove in the living room and a Tappan-Rice cook stove in the kitchen.

Never again to my knowledge was there a time where the flood waters entered the house.

Ten years later, however, my mother and I were alone on the farm. My older brother Edward had married and moved to Bedford, Ohio. My father and Aunt Ellen had both passed away.

We had sold all the livestock except for one milk cow and one carriage horse and a few chickens. Since I was finishing school at Northfield High School and had enrolled at Hammel University in Akron, Ohio, I could only handle a good-size garden, the orchard, and the barn chores.

That year, in the summer of 1923, there was another storm and water crested only high enough to overflow the canal into our front yard. Prior to this time, I had built a revetment to prevent the flood waters from again going into the cellar!

My mother and I did not have to evacuate this time … we had only ourselves there to meet the challenge.

But that is another story!

NPS Collection

Tags

- cuyahoga valley national park

- ohio

- midwest

- transportation

- transportation history

- national register of historic places

- nr

- historic district

- cultural landscapes

- ohio and erie canal

- canal

- towpath trail

- ohio to erie trail

- industrial heartland trail network

- ohio and erie canalway

- lock

- flood of 1913

- disasters

- family

- farm