Last updated: October 17, 2024

Article

From Hammer to Musket: The Tragedy of Timothy Bigelow

NPS/Horrocks

The Learned Blacksmith

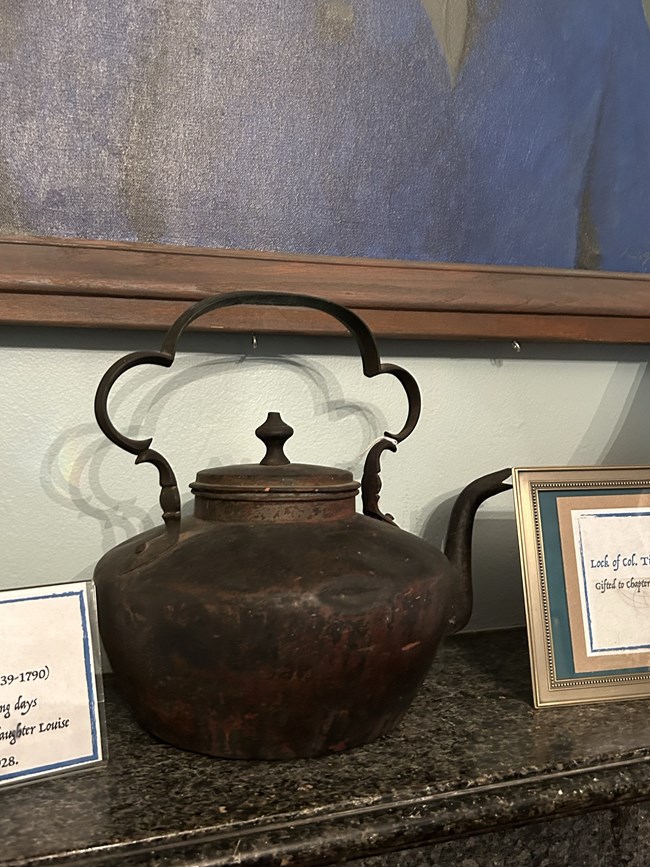

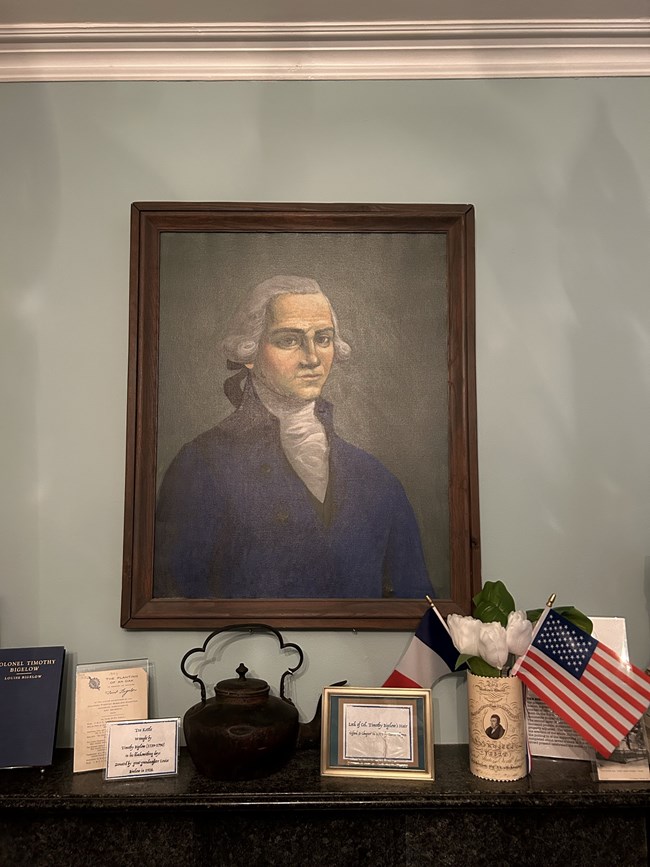

The fifth son of Daniel and Elizabeth Bigelow, Timothy Bigelow was born on August 12, 1739. He spent most of his life living in and around Worcester, Massachusetts. Following in his great-grandfather’s footsteps, Timothy apprenticed as a blacksmith. Bigelow’s strong personality and large frame made him a strong presence in the community. He was a natural leader. A biographer recorded a description of Bigelow: “His figure was tall and commanding; his bearing was erect and martial, and his step was said to have been one of the most graceful in the army…Bigelow possessed a vigorous intellect, an ardent temperament, and a warm and generous heart.”

Unlike his ancestors, Timothy had little desire to be a colonist. He was later described as a “zealous patriot.” He organized a “political society” which met regularly in his home. In 1774, they joined forces with the Sons of Liberty based in Boston. His involvement with this organization set him on a trajectory towards fighting for independence. In due time, Bigelow replaced his hammer with a musket.

Courtesy of Col Timothy Bigelow Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution

TO ARMS!

In the early morning hours of April 19, 1775, the call “To Arms! To Arms!” rang out in the streets of Worcester. Under the command of Captain Bigelow, 110 men mustered on the common. In the early morning hours, they commenced a march towards the battlegrounds of Lexington and Concord. His troops did not make it in time to participate in the fateful fighting around the North Bridge and the long retreat back to Boston, but they followed in the wake of the battle, seeing the dead and wounded, discarded muskets, cartridge boxes, and blankets. After five days of active service, Bigelow and his company returned to Worcester. A few weeks later, Bigelow was promoted to the rank of Major while serving in Cambridge as part of the Siege of Boston. Bigelow and the men under his command remained an active part of the siege until the early fall of that year.

The Folly of Quebec

After the capture of Fort Ticonderoga on May 10, 1775, General Phillip Schuyler planned an invasion of the Canadian Provinces. Schuyler intended for two Continental forces to meet and surround Quebec City. He hoped the armies could earn a decisive victory and garner French-Canadian support. Troops under the command of Colonel Benedict Arnold marched north from Boston to attack the eastern region of the city. Bigelow and a handful of Worcester volunteers joined Arnold’s command of about 750 soldiers on the march north.

From the beginning the Continental forces struggled to survive. Improperly outfitted and poorly supplied, Arnold’s forces labored northward. Difficult terrain and inaccurate maps only compounded their troubles. For six harrowing weeks, Bigelow and his comrades fought to survive, scrounging up what little food they could scavenge. In a letter dated October 24, 1775, Bigelow wrote to his wife Anna:

Dear Wife. I am at this time well, but in a dangerous situation, as is the whole detachment of the Continental Army with me. We are in a wilderness, nearly one hundred miles from any inhabitants… and about five days provisions on an average for the whole. We are this day sending back the most feeble and some that are sick. If the French are our enemies… there will be no alternative between the sword or famine.

Conditions did not improve for the Continental forces. Attempts to establish a siege were thwarted by the Continental’s inability to dig trenches because the ground was frozen thanks to the already harsh winter conditions. Starvation and freezing temperatures diminished the effective fighting force. To make matters worse, smallpox broke out in the American camps. General Richard Montgomery and Arnold had to make a decision. Their forces dwindled while British Governor General Guy Carleton bolstered his already strong defenses of the city.

On the day after Christmas, Montgomery held a council to discuss the plan of attack. Bigelow voiced his opposition. Against his better judgement and perhaps out of a sense of duty, Bigelow reluctantly agreed to lead his men in the attack. His reluctance, however, was perceived by some as cowardice. A few days later he was “complained of cowardice” for dodging an artillery shell. Later, Colonel John Lamb brought Bigelow up on military charges of cowardice; the court acquitted Bigelow, but his reputation was tarnished.

During a nighttime attack on New Year’s Eve, the malnourished and sickly soldiers of Montgomery and Arnold’s commands charged the well-fortified city. A force of about 400 Continentals (including Bigelow) breached the British fortifications. In the early morning chaos, a fight broke out in the crammed city streets. The British troops captured the Continental Troops. In perhaps one of the most lopsided defeats of the war, the attack had failed. Bigelow and his troops were now prisoners of war. Life in a prisoner of war camp was unpleasant, even for an officer such as Bigelow. He was imprisoned for the next seven months until he was released in a prisoner exchange.

Courtesy of Col Timothy Bigelow Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution

Saratoga, Valley Forge, and Monmouth

Bigelow did not remain home in Worcester for long. Upon his return, he was promoted twice: first to Lieutenant Colonel, then to Colonel. He was appointed the commander of the 15th Massachusetts Regiment which consisted of 8 companies of men from Berkshire, Bristol, Middlesex, Essex, Suffolk, Cumberland, and Worcester Counties. This regiment was eventually assigned to the Northern Department, part of Major General Horatio Gates’s army.

The 15th Massachusetts Regiment was present for one of the more notable events of the war when General John Burgoyne’s Army surrendered at Saratoga, New York. Following the surrender, Bigelow’s men were reassigned to General Washington’s army outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This in turn put Bigelow at Valley Forge in winter 1777 and early 1778. The hardships endured by Bigelow and his comrades at this winter encampment are undeniable. Harsh winter conditions, inconsistent supplies, and illness affected the roughly 12,000 soldiers and 400 civilians that inhabited the 1,500 log huts encircled by two miles of fortifications. About 2,000 soldiers succumbed to illness and malnourishment. These winters of service were hard on Bigelow. His once robust physique was undoubtably weakened.

In the summer of 1778, Bigelow and the 15th Massachusetts Regiment fought at the Battle of Monmouth. Washington attempting to destroy the rearguard of Sir Henry Clinton’s British Army as it marched to New York City, ordered General Charles Lee to attack. What at first seemed to be promising, nearly ended in disaster when Lee failed to press his advantage. British troops under Lord Charles Cornwallis took the initiative and attacked Washington’s troops. Bigelow’s 15th Massachusetts Regiment (under Rhode Islander Nathaniel Greene’s command) put up a strong resistance to Cornwallis’s forces. After a long fight in hot and humid conditions, Cornwallis removed his troops from the field. A great opportunity eluded Washington that day, but Bigelow’s men had fought well, helping to avert disaster. Following Monmouth, the 15th Massachusetts spent the next year moving around New England and New York, guarding against British movements at strategic fortifications.

The End Game

On October 14, 1780, General Washington appointed General Nathaniel Greene as the commander of the Southern Department of the war. Bigelow had long respected and admired Greene, and they seem to have struck up a friendship during the conflict. With Greene promoted to command once again, Bigelow requested a transfer for his regiment to the Southern Department. This was an unusual request for the native New Englander to want to be moved so far away from home, but Bigelow respected his former commander and may have wanted to move away from the tedious work of garrisoning forts. Washington approved his request, and the 15th Massachusetts was reassigned to Greene’s department.

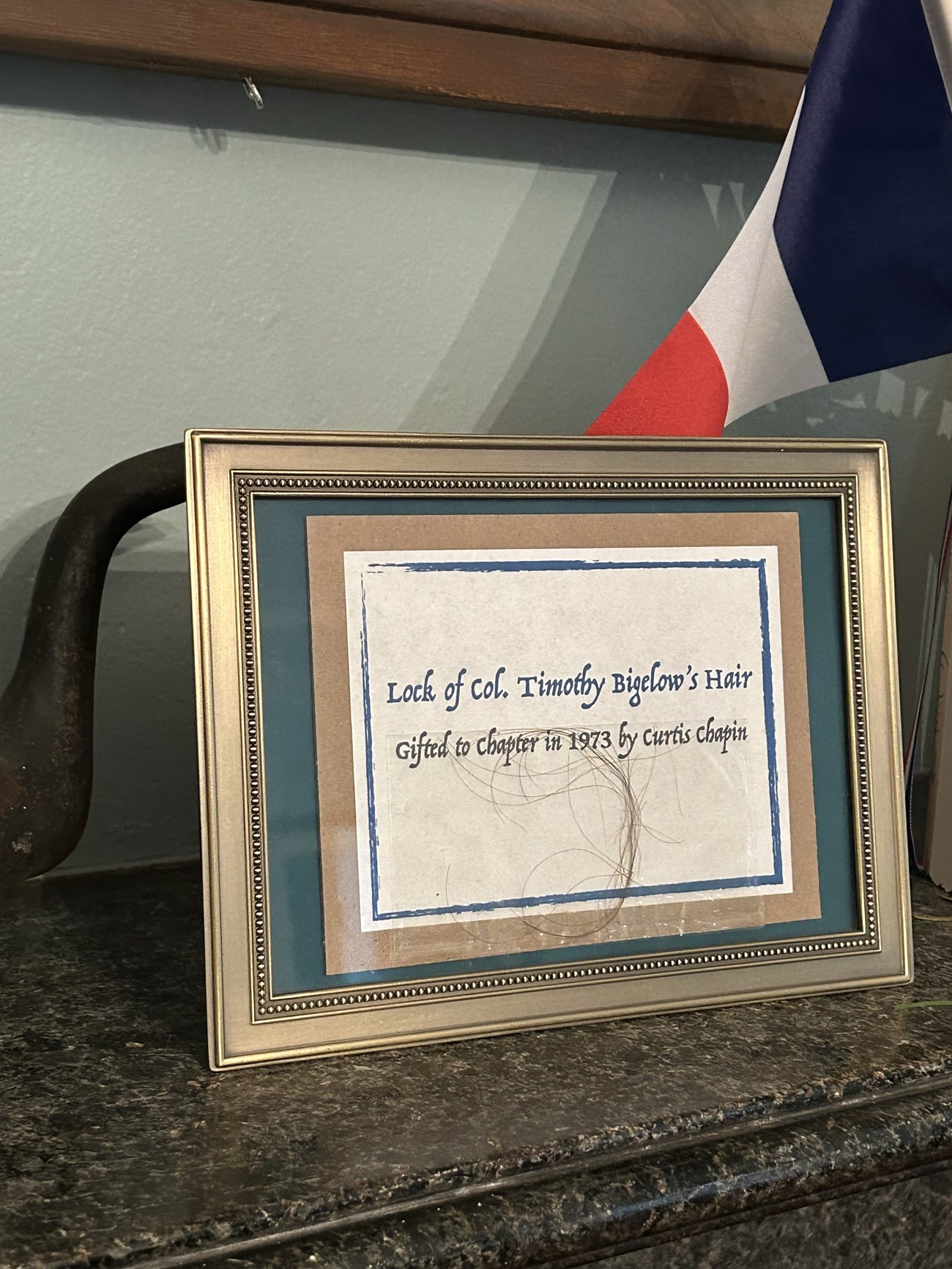

Bigelow’s men did not arrive back in the theater until late summer of 1781. They found the armies in eastern Virginia. On the shores of the Chesapeake Bay, the Continental and French forces were besieging Lord Cornwallis’s troops at Yorktown (September 28 – October 19, 1781). During the siege, Bigelow was temporarily assigned to the Marquis de Lafayette’s staff. Bigelow developed a deep respect and friendship with the young Frenchman. Lafayette trusted Bigelow, and he would be a key staff member during the fateful three weeks which culminated with the British surrender on October 17. After Yorktown, Bigelow returned to command the 15th Massachusetts until they were disbanded at West Point, New York on January 1, 1782.

Courtesy of Col Timothy Bigelow Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution

The Return Home

At the war’s conclusion, Congress granted Colonel Bigelow 23,040 acres of land in the Vermont Territory as a form of backpay for his nearly eight years of service. This region became the future capital of Vermont, Montpellier. Bigelow never inhabited this land and sold it all in an attempt to pay off mounting debts he accrued during the war. His time in service took a toll. Upon his return, Bigelow’s family was struggling, and he was in poor health. Years earlier, Bigelow had written home that he feared “no alternative between the sword or famine.” Bigelow survived the war only to succumb to other battles. Bigelow died in a debtor’s prison in squalid conditions, largely forgotten or neglected by his friends and comrades. He was 50 years old.

The Worcester Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is named in his honor. In their account of their namesake's story, they do not shy away from the fact that Bigelow “returned home in ill health, with no money or future.” Bigelow was among “the most distinguished and daring patriots of the Revolution, ready to hazard his all, whether life or property, for the cause in which he believed.” In spite of leading his comrades through some of the most challenging epochs of the War for Independence, Bigelow died penniless, having paid the ultimate price when he left his hammer to pick up a musket.

A special thanks to the members of the Colonel Timothy Bigelow Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) who graciously welcomed park staff to their chapter house and shared the artifacts and resources associated with Colonel Bigelow highlighted in the article.