Last updated: June 15, 2023

Article

For the Love of Monarchs: How We Joined the Push to Save a Beloved Butterfly

We spent the summer of 2022 learning to be good stewards of monarch butterflies. It was an unforgettable experience.

Image credit: NPS / Sonya Popelka

Two decades ago, millions of monarch butterflies occupied their overwintering sites in California and Mexico. Some say the sound of their wingbeats was like a rippling stream. But it is hard to hear that sound today, as monarch populations have collapsed over 80 percent in North America since 2005. These large, familiar, strikingly colored creatures have declined in numbers because of pesticide use, diminished food sources, disease, and habitat loss. These stressors are compounded by climate change. Through the Latino Heritage Internship Program, we collaborated in 2022 to study this imperiled species in Grand Canyon National Park and Dinosaur National Monument. Our work will help scientists better understand the butterflies’ migration routes and breeding habitats and will aid public land managers in protecting them.

Tiny Travelers with Huge Impacts

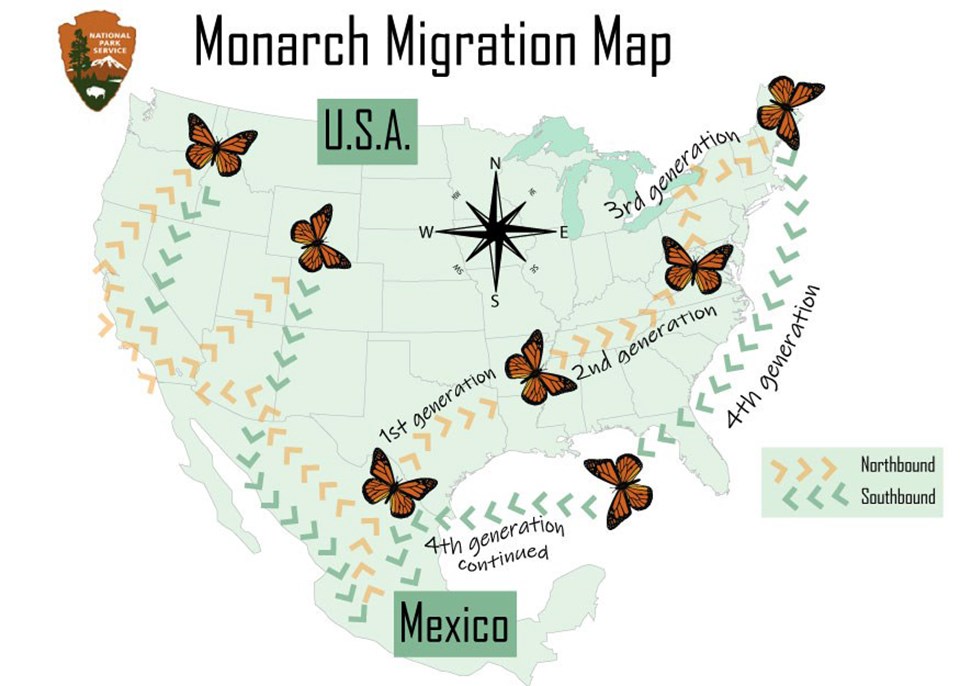

The two main populations of monarch butterflies in North America, eastern and western, are separated by the Rocky Mountains and where they overwinter. In winter, western monarchs journey to warmer locations in the southwest deserts of Arizona and California, such as Lake Havasu, Yuma, Phoenix, Tucson, and Palm Springs. Some even head further south to Mexico and join their eastern kin. But most make the journey to several locations on the central California coast. In the warmer spring months, western monarchs abandon their coastal and desert roosting sites and fly inland and north in search of feeding and breeding grounds.

Image credit: NPS / Sarah Sparhawk

Four generations of western monarchs make the 3,000 mile journey inland in relay fashion. As breeders, the first three generations each live for only about four weeks. The fourth generation, the “mega-migrators,” enter a state of reproductive diapause, where they stop reproducing. This allows them to survive harsh winter conditions and conserve energy as they fly to their wintering grounds. These mega-migrators live up to nine months. At the end of their winter stay, the mega-migrators will end their reproductive diapause and begin to breed as they fly north, thus beginning a new annual relay of monarchs.

Some Mexican cultures believe monarch butterflies to be the souls of departed family members. They believe that monarchs bring the souls of their relatives to the living world for one night, on Día De Los Muertos, the “Day of the Dead.”

The larger, eastern monarch population flies to forests in the central Mexico highlands, where cool temperatures and moist air promote the growth of oyamel fir trees. These trees are where eastern monarchs spend the winter. Some Mexican cultures believe monarch butterflies to be the souls of departed family members. They believe that monarchs bring the souls of their relatives to the living world for one night, on Día De Los Muertos, the “Day of the Dead.” This day occurs in the first week of November, a spiritual legacy passed down from generation to generation. The monarch butterfly thus has great importance in Mexican culture, beyond its biological role.

Image credit: NPS

A Beloved Butterfly in Peril

One of the most recognizable insects in the world, monarch butterflies play a pivotal role as pollinators. Many wildflowers rely on monarch butterflies to transport pollen and assist in plant reproduction. By protecting and restoring monarch butterfly habitat, we create healthy ecosystems for other pollinators to thrive. Monarch butterflies also serve as icons for cultures around the world, and their popularity makes them a flagship species for conservation.

But monarchs are in serious trouble. Western populations have decreased by an astounding 99 percent since the 1980s. This is a result of several factors. One of these is widespread pesticide use, which kills insects indiscriminately, including butterflies. Another factor is herbicide use on plants, which harms their food sources. The butterflies are also susceptible to a debilitating parasite, which compromises their ability to grow or fly. And urban and agricultural development in Central Mexico and California’s Central Coast, where monarchs overwinter, have caused monumental habitat loss.

In 2020, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service declared that listing the monarch butterfly under the Endangered Species Act was warranted but precluded.

Rising average temperatures and more frequent and intense wildfires from climate change are also factors. These impair the distribution and numbers of milkweed plants, the monarch caterpillar’s only food source, and other plants that feed the adults, disrupting their natural migration cycle. With such alarming trends, it’s no surprise that monarch conservation is a priority for land management agencies like the National Park Service.

In 2020, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service declared that listing the monarch butterfly under the Endangered Species Act was warranted but precluded. This was because of other listings that had higher priority. In 2022, the agency released a Candidate Notification of Review. In this review, it continued listing the monarch butterfly as warranted but precluded. The monarch's listing priority number remained at 8. The listing priority numbers range from 1 to 12. The lower the number assigned, the higher the priority listing is for a species. The agency plans to reevaluate the eligibility of protecting monarchs under the act in 2024.

Out of the Classroom and into the World of Scientific Inquiry

Image credit: NPS

The Latino Heritage Internship Program works with the National Park Service and Environment for the Americas to create scientific and cultural internship opportunities for young Latino adults. Co-author Cassandra Cavezza received an email through the dean of the College of the Environment, Forestry, and Natural Sciences at Northern Arizona University about an internship possibility. It was for working with monarch butterflies at Grand Canyon National Park. The location was close. Cavezza had a previous background with monarchs, and this was an opportunity for her to connect more with her Latino heritage. Merging the two seemed like a possibility of a lifetime to grow in her culture and also make a difference as a Latino in science.

Image credit: NPS / Juan Pablo Esparza-Limón

Co-author Juan Pablo Esparza-Limón learned about the Latino Heritage Internship Program by listening to previous interns’ experiences through the Conservation Diaries, a National Park Service podcast series. He quickly realized the Latino Heritage Internship Program fused two core elements of his identity: being a geologist and being a Latino. The idea of joining a supportive Latino program that included outdoor science education and nature conservation encouraged him to apply online for a summer position.

Outside of our home parks, a highlight of our Latino Heritage internships was traveling to Washington DC for the Career and Leadership Workshop. In this week-long professional development training, we presented an outline of what our summer internships would look like. We met and learned about other Latino Heritage Internship Program intern projects. Key speakers such as Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland and Director of the National Park Service Charles F. “Chuck” Sams III shared inspiring words about inclusivity and diversity in the future of the National Park Service. This experience gave us the confidence to own our Latino cultural heritage while serving in our internships.

Our Internships Begin

Grand Canyon National Park and Dinosaur National Monument are 500 miles apart. Yet they have a resource in common: rivers that are part of the greater Colorado River Basin. In Dinosaur, the Yampa and Green Rivers are major tributaries of the Colorado River, which runs through the Grand Canyon. Habitat along the river’s edge—the riparian zone—has milkweed and other nectar-rich plants. Monarchs breed and feed on these plants, and the river corridors in these two parks provide important habitat for the butterflies. The parks wanted us to help them continue the search for answers about the monarch populations moving through them.

Throughout summer 2022, we helped Grand Canyon and Dinosaur restore and propagate milkweed and other native plants. We also monitored monarchs and educated people about monarch life cycles and conservation.

Cavezza is originally from Texas but has been living in Flagstaff, Arizona, while going to college. The drive from Flagstaff to Grand Canyon National Park is around one hour and twenty-five minutes. It was easy for her to drive to Flagstaff on the weekends if necessary. Esparza-Limón began his travels in his home state of Texas. Along his road trip to Utah, he stopped to hike the Crater Rim Trail of Capulin Volcano National Monument in New Mexico. He also spent an afternoon meandering through the tilted rock formations of the Garden of the Gods Park in Colorado. Throughout summer 2022, we helped Grand Canyon and Dinosaur restore and propagate milkweed and other native plants. We also monitored monarchs and educated the public about monarch life cycles and conservation.

Image credit: NPS / Stefano Cavezza

Hosting Host Plants in Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon National Park has two monarch butterfly habitat creation sites, one located on each rim. These sites are filled with host (i.e., milkweed) and nectar-rich plants for many different pollinators. Staff propagate and grow these plants in a greenhouse on the south rim of the park. They are then planted in the garden or used for park restoration projects. Cavezza helped biological science technicians inventory seeds and plant seedlings at the greenhouse that were destined for the habitat creation sites. She and the rest of the crew planted the seedlings on both sites throughout her internship. Cavezza also produced a short video called "Milkweed and Monarchs."

- Duration:

- 4 minutes, 14 seconds

Milkweed is a critical plant for the monarch butterfly life cycle, but monarchs use many different milkweed and nectar-rich plant species throughout Grand Canyon National Park and Dinosaur National Monument. The milkweed and nectar-rich plant species in the parks differ according to region. Milkweed plants are the only ones monarch caterpillars eat, but adult monarchs and other insect species rely on nectar-rich plants in both parks. First released in the Winter 2022 issue of Park Science magazine.

Discovering the Secrets of Monarch Migrations

Grand Canyon National Park and Dinosaur National Monument both partner with the Southwest Monarch Study to do scientific research on western monarch butterflies. The parks aim to confirm the key migration paths of monarchs in the American Southwest. Their long-term goal is to fortify monarch habitats along identified routes in the parks. We helped the parks capture wild adult monarchs, tag, and release them.

Image credit: NPS / Juan Pablo Esparza-Limón

Along with park staff, we gently placed waterproof identification stickers on the wings of adult monarch butterflies. By tracking the individually tagged insects, scientists can map the locations that the monarchs visited. Our hope was that one of the butterflies we tagged would be found in another state or another country, helping to determine the migration pathway of monarch butterflies across North America.

Dinosaur National Monument is part of an interagency coalition of resource managers. These managers work together to conserve pollinators at the landscape level in the Uintah Basin of northeast Utah. Kelly Lynch, a biological technician with Ashley National Forest, attributes the tagging project’s success to the “astounding collaboration” between different organizations.

Partners include the National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, Utah Department of Natural Resources, Natural Resource Conservation Service, Utah State University, and dedicated members of the public.

"One of the monarchs tagged at Stewart Lake State Wildlife Area along the Green River was recaptured 111 miles straight south along the Colorado River near Moab."

“Throughout the season, we routinely survey for monarchs at twelve locations that contain prolific patches of milkweed and nectar-rich flowering plants,” said Lynch. “We were very excited to hear that one of the monarchs tagged at Stewart Lake State Wildlife Area along the Green River was recaptured 111 miles straight south along the Colorado River near Moab. Thanks to the folks who reported the sighting, we know that the Green River is likely a travel corridor for the monarchs.”

Southwest Monarch Study coordinator Gail Morris said another factor in the project’s success is the physical condition of the butterflies. She said that after tagging more than 22,000 monarchs and recovering 75, “We now know that monarchs with wings in excellent condition or [that] are recently enclosed are the most likely to successfully migrate to an overwintering site. By reporting data collected with the tags, we can…learn about…key hallmarks of the monarch migration.”

Gauging a Wing-Deforming Parasite’s Damage

As if habitat loss and other stressors weren’t enough, monarch butterflies are vulnerable to infection by a debilitating protozoan parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha. The parasite does not necessarily kill the adult monarch butterfly, but it can cause wing deformities that affect the insect’s flight. Infected monarchs find it harder to reach their overwintering sites and crucial feeding grounds.

At Dinosaur National Monument, Esparza-Limón helped host a citizen science project, Project Monarch Health, in partnership with the University of Georgia. Project Monarch Health analyzes the effects of the parasite across the North American monarch butterfly population. Parks assess monarchs for this parasite concurrently with the Southwest Monarch tagging project. They and participating scientists want to know more about how it affects the butterflies’ ability to reproduce and migrate.

Esparza-Limón, park staff, and citizen scientists used clear stickers to retrieve parasite samples from the abdomens of captured adult monarch butterflies. At the end of the migratory season, the park shared tagging and parasite data with scientists and the Utah Pollinator Pursuit survey. The survey helps to identify areas in Utah communities that provide good habitat for monarchs.

Educating Others

Through educational presentations and activities, we discussed our work with students and visitors to promote science literacy and land stewardship. Our conservation projects enabled diverse groups to create a personal connection with monarch butterflies. Through conservation education, we helped curious individuals realize their role in preserving monarch butterflies and how their active participation could better the ecosystem and their communities.

Image credit: NPS / Jeanne Yost

At the Grand Canyon School, Cavezza taught third grade students about the monarch butterflies’ life cycle, how and why we tag monarchs, and which plant species they feed and breed on. She taught the students how to tag monarchs with stickers and diagrams. She used a puppet to demonstrate how to safely capture monarchs, which the students practiced doing. With the help of her mentor, National Park Service biological technician Tara Chizinski, she also taught students how to collect milkweed seeds and capture and tag monarchs.

Esparza-Limón helped develop evening ranger programs for the Green River Campground at Dinosaur National Monument. These took an in-depth look at the monarch’s developmental stages, from egg through juvenile and chrysalis to adult. In the ranger program, he fostered a discussion that encouraged compassion and reverence for monarch butterflies.

Image credit: NPS / Sonya Popelka

Esparza-Limón and park staff also invited 50 curious eighth graders from a local school to participate in an interactive educational program. For this program, Esparza-Limón demonstrated how to properly capture and handle a monarch butterfly with an insect net. The program gave students a chance to personally connect with the monument’s natural resources, an alternate learning environment to the traditional classroom setting.

Cross-Training Enriched Our Experiences

Our internships gave us an exciting opportunity to cross-train at one another’s home parks. With the help of staff from the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, we co-hosted a public monarch tagging event at Dinosaur National Monument. During this early morning program, we displayed the tagging process step-by-step and told the story of the monarch butterfly’s life cycle and migration.

A week later, Esparza-Limón visited Cavezza and her team at Grand Canyon National Park. Together with the Ancestral Lands Conservation Corps, Zuni Pueblo crew, we collected native milkweed seeds, helped plant milkweed on the newly developed Pima Point pollinator garden, and tagged monarch butterflies.

Monumental Moments

There were many stand-out moments for us this summer, but our first-time-ever river-rafting trips were among the top! Cavezza rafted the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon for nine days. Her river trip focused on halting the encroachment of invasive plants and maintaining cultural sites, but she saw a few monarchs along the way!

Image credit: NPS / Tania Guardado

Esparza-Limón joined Dinosaur National Monument’s fourth annual multi-day whitewater rafting trip to look for monarchs. They looked along the Green River near the peak of the butterflies’ migration in mid-September. Esparza-Limón was part of a crew of 12 interagency biologists, volunteers, and skilled boat operators on four rafts. They navigated rapids, riffles, and steep banks to search for milkweed and monarch butterflies in all life stages. On the second day of the rafting trip, the group captured a newly enclosed monarch (a rare sight!). They acted swiftly to tag it before watching it take flight for the first time. Esparza-Limón even got some training time on the oars!

Image credit: NPS / Sonya Popelka

Life-Changing Lessons

Cavezza’s internship taught her many things. She learned that it’s okay to experience things solo and how to speak up for herself in the workplace. This internship solidified her choice of career in the field of environmental science. She hopes to gain new opportunities and experiences like this past summer’s, and hopes that one day she could be one of the people making changes for the planet.

Having meaningful conversations with park staff and visitors extended Esparza-Limon’s sphere of knowledge past textbooks. His experience at Dinosaur National Monument was challenging yet rewarding. It gave him a new sense of personal confidence in the great outdoors and about communicating science. The internship shifted his career goals. He now plans to pursue a career with the National Park Service post-graduation in hopes of extending the accessibility of the agency to Latinos and other underrepresented minority groups.

Image credit: NPS / Juan Pablo Esparza-Limón

The Importance of Optimism

Ultimately, we strive to educate people about the value of conservation. We believe it is our duty to share our knowledge and be a positive influence for conserving animals like the monarch butterfly. Despite prevailing trends, we think it is important to remain optimistic on the status of monarchs. We agree with Ashley National Forest biologist Natasha Hadden, who told us, “As one person you may be able to move a few boulders, but with a multitude of collaborators, we can move mountains.” Hadden loves that Ashley National Forest collaborates with Dinosaur National Monument and the states of Utah and Arizona to conserve pollinators like the amazing monarch. So do we.

About the authors

Cassandra Cavezza is a junior at Northern Arizona University studying environmental sustainability. She has created pollinator gardens and planted native host and nectar rich plants around her home in Houston, Texas, since 2018. The gardens release thousands of monarchs. Image used by permission of Cassandra Cavezza.

Juan Pablo Esparza-Limón's cultural ties to Mexico inspired him to do research on the monarch butterfly's migratory journey. He is a senior at Southern Methodist University studying geology. Image used by permission of Juan Pablo Esparza-Limón.

Tags

- dinosaur national monument

- grand canyon national park

- interns

- internships

- pollinators

- butterflies

- monarchs

- milkweed

- cassandra cavezza

- juan pablo esparza-limón

- animals

- plants

- environment

- educate and interpret

- ps v36 n2

- park science magazine

- park science journal

- stories by women authors

- latino heritage internship program

- latino heritage intern