Last updated: April 10, 2025

Article

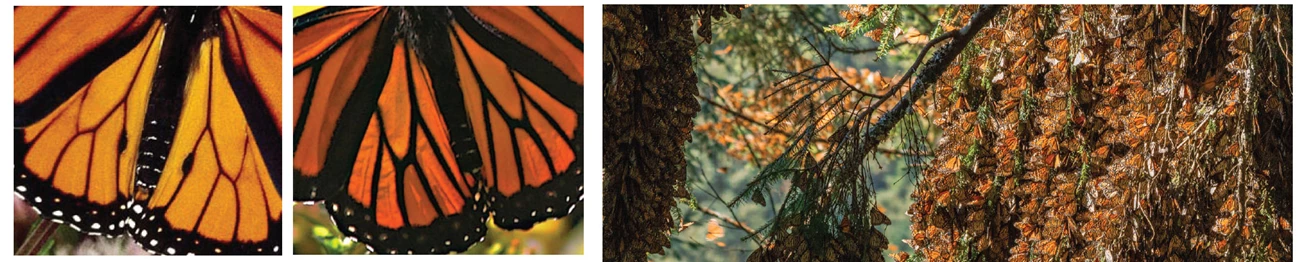

NETN Species Spotlight: Monarch Butterfly

How would you like to be the Prince of “Orange”? Turns out it’s more than a color - it was a place too, located in what is now southern France. Legend holds that Prince William of Orange (later King William III) was so adored by some early European settlers to North America that they bequeathed the name “Monarch” to our very orange and regal butterfly in his honor. Whether this story is gospel or apocryphal, the monarch regardless is a majestic insect worthy of the title. Metamorphosis, mimicry, and a mind-blowing migration may indeed make it the king of all butterflies.

Instar Master

To misquote a Chinese proverb: “Even a journey of 3,000 miles begins with a first step.” In the case of monarchs, step 1 is being laid as an pinhead-sized egg on a milkweed plant. After 4 days, it hatches a single, hungry, 2 mm long caterpillar. Its first meal is its own egg case. From there it seldom stops eating for the next 2-weeks. It devours the leaves and flowers of milkweed, going through 5 “instar” stages and growing over 20X (up to 45 mm) in length and 2,700X in weight. Each instar stage transformation is marked by the shedding of its exoskeleton skin, which it often eats. Monarchs are the ultimate recyclers.

Metamorphosis Magic

Whoever coined the term transmogrify (to transform in a surprising or magical manner) may well have just witnessed a monarch caterpillar turn into a “chrysalis.” About 10 hours before shedding its skin for the 5th and final time, it spins out a wad of silk from which to suspend. What happens next is such a dramatic change you really need to see it to believe it. Its body splits at the head, and the caterpillar wriggles to shed its exoskeleton like an all too-tight pair of pants, revealing the chrysalis underneath. It soon hardens and for the next week or two the butterfly develops within this protective case. To maximize camouflage, the black and orange colors don’t develop until just before emergence, and can be seen through the transparent skin of the chrysalis.

Who’s Copying Who Here?

“Viceroys and monarchs exemplify a classic case of Batesian mimicry.” Not just something to say to sound pretentious and alienate your friends, it is also very likely wrong. True Batesian mimics are unrelated organisms with one that is defenseless/harmless copying the colors and patterns of a dangerous/poisonous organism in hopes to trick would-be predators to leave it in peace. Viceroys do indeed resemble monarchs, but it can also be said that monarchs resemble viceroys. In the 1990’s researchers proposed these butterflies are actually Müllerian mimics: similar looking dangerous organisms that mutually benefit from their like-likenesses. Monarchs are packed with toxic substances from feeding on milkweed as caterpillars, making them unpalatable to many potential predators. Similarly, viceroy caterpillars feed on willows and poplar leaves ingesting chemicals that produce bitter-tasting compounds.

Right image: Rafael Saldaña

The Generation Gap

It takes four generations going through four life stages each to complete the journey from Mexico to the northeastern U.S. every year. It can be a little confusing to tie all together, and almost feels like you need one of those police-drama corkboards with tacked-up photos and crisscrossing strings to keep track, but here goes an attempt to explain. Let’s start by jumping on the cycle down in sunny Mexico because, well, why wouldn’t you? It is here in their wintering grounds that hibernating monarchs begin to awake in February/March. They then head north into Texas and surrounds to lay eggs on milkweeds in March/April, after which most (more on this later) perish. These eggs represent Stage 1 of Generation 1 of the new monarch year. With me so far? They hatch and go through the other 3 life stages (larva, pupa, adult), then continue farther north and east. They live several weeks, laying eggs (Stage 1, Generation 2) on milkweed before they expire. This process continues until the 4th generation, oft-dubbed “the super generation”, which live for months and are emerging about now in much of the northeast. They do not look to reproduce just yet, but like a carbo-loading marathoner, over the next several weeks these butterflies will bulk-up on flower nectar. They are prepping for the long, arduous journey back to their ancestral wintering grounds - a place they have never seen - in the mountains of Mexico about 3,000 miles away. Once there, they join millions of other monarchs going into hibernation, only to arouse in about 5 months to begin the cycle anew. It was once thought that all of these 4th generation monarchs died after laying eggs in spring, but recent science has found that up to 10% continue on and make the complete return journey all the way back to the northeast. These “Methuselah” (mythical biblical figure that lived to be over 900 years old) monarchs can live up to 9 months on their 6,000 mile round-trip journey. Okay, you can put down the tacks and string now.

The Return of the Parákata

The fall arrival of monarchs to Mexico has been an important natural and cultural event for centuries. The native Purépecha Indians of the region refer to them as parákata, or in English: the “harvester butterfly,” whose appearance signals it’s time to harvest the life-sustaining corn crop. Conversely, the monarchs return also kicks off the annual Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) festival as the Purépecha believe monarchs are the souls of their deceased ancestors briefly returning to visit them.

Monarchs are thought to be the only true migratory butterfly on Earth, but why do they bother? Progressively travelling northward from Mexico in spring and summer continually supplies their caterpillars with freshly emerging milkweed plants, while adults gain access to flowers with less competition for nectar. As for making the return trip to Mexico in fall, ask any realtor and they will tell you there are three key reasons to settle into an area: location, location, and location. The isolated spots in the valleys of the Mexican mountains provide the perfect conditions for monarchs. They have cool (but not freezing) stable weather, high humidity, and offer protection from desiccating and damaging winds.

The Rise and Fall of the Monarch Monarchy

Researchers discovered the monarch Mexican wintering grounds relatively recently in 1975. Up until the mid 1990’s numbers there remained stable and even grew, reaching a peak of monarchs covering about 52 acres and numbering over 1-billion individuals in 1996. After that record high, it began to rapidly decline reaching a record low in 2013/14 of less than 2 acres and about 30 million individuals - a population drop of over 95%. The story is similar in North America, where the largest population of monarchs that migrate between Mexico and the Midwest fell 80%: 1-billion in the 1990’s to 200 million by 2018. They certainly seem to be on a path to extinction. What is going on? As with most complicated problems, the issues facing modern migrating monarchs are many-fold, climate change and loss of habitat amongst them. But there is one issue that stands out above all the rest in the United States.

Got Milkweed?

You likely already picked up on the fact that milkweed is essential for the survival of monarchs since it is the only food source for their caterpillars. Milkweed is being lost due to changing agricultural practices in the Midwest, where 50% of the monarch population is typically produced each year. Their population drop parallels the introduction and adoption of genetically engineered crops that are designed to survive the application of proprietary herbicides. Alas, milkweed (and many other beneficial plants) cannot. A 2013 study by Iowa State and the University of Minnesota estimated nearly 60% of milkweed died off in Midwestern farm fields since 1999. And as demand for corn has increased, so has pressure to convert open land for agricultural production using these herbicide resistant plants and other pesticides.

One year does not a trend make, but...

Numbers aren’t final, but anecdotally it has been a banner year for monarchs so far. Journey North and the Vermont Center for Ecostudies think it could one of the best in 20 years. In the northeast, the arrival of monarch butterflies coincided with a warm, dry spell and plenty of fresh milkweed. In the Midwest, the University on Minnesota has estimated an almost 60% increase in caterpillars. Changes to highway and power line mowing regimes are likely partly to thank. Optimism is high that the Mexico population will be double what it was last winter – a measly 6 acres. As exciting as this is, it would need to continue for many years to be considered a recovery. Much still needs to be learned about how pesticide/herbicide use is affecting monarchs at all life stages, and climate change and habitat loss are still major issues. The USFWS is contemplating whether to declare monarchs an endangered species, and will make a ruling in Dec. 2020.

For more information

Learn how you can help the monarch in your yard, caterpillar to adult, from the US Fish & Wildlife Service.

- Become a part of a nationwide network on monarch trackers for one of these citizen-scientist initiatives: Journey North, Mission Monarch, and MonarchWatch.

Tags

- acadia national park

- appalachian national scenic trail

- eleanor roosevelt national historic site

- home of franklin d roosevelt national historic site

- marsh - billings - rockefeller national historical park

- minute man national historical park

- morristown national historical park

- saint-gaudens national historical park

- salem maritime national historical park

- saratoga national historical park

- saugus iron works national historic site

- vanderbilt mansion national historic site

- weir farm national historical park

- species spotlight

- netn

- inventory and monitoring division

- monarch butterflies

- monarch watch

- milkweed

- migratory species

- insects & invertebrates

- citizen science