Part of a series of articles titled Elephant Seal Tales.

Article

March: Catastrophic Molt: It's Not As Bad As It Sounds

The Catastrophic Molt

Anything with "catastrophic" in its name sounds seriously bad, but before we evaluate how bad elephant seals' catastrophic molting really is, let’s define molting: "Molting means the periodic shedding of feathers, hairs, horns, nails, shells, and skins - any outer layer. Molt is from the Latin mutare meaning 'to change'" (Merriam Webster).

When we brush our hair, for example, we consider it natural that some hair remains in the brush. We don't usually shriek in horror, "I'm molting!"—even though we are!

The elephant seal catastrophic molt (which simply means that their fur and top layer of skin comes off in large patches) is more dramatic than a few hairs in a hairbrush. As the photo illustrates, the seals definitely look ragged when they are in the midst of the molt. Normally, when seals are in the ocean, their bodies direct blood flow away from their extremities and towards the core of their bodies so they can keep their vital organs warm and functioning in the cold ocean temperature. But, because the act of molting requires seals’ bodies to direct blood flow to the surface of their skin, the seals have to be on land during the molt. Otherwise, they (and their vital organs) would become too cold. So that's why seals must sequester on the beach, out of the cold ocean, for the entire molt process. And, as is usual for seals, whenever they are on land, they fast.

But molting is not as dramatic as what's been going on at Point Reyes Beaches over the last few months. Let's recap what these elephant seals, these truly charismatic megafauna (which just means big animals!), have been up to.

Recap of the Breeding and Mating Season

Since February, the month of elephant seal mating and impregnation, things have quieted down quite a bit. Now, at the beginning of March, most females, having completed giving birth and nursing pups, have left the beaches.

Of course, once the cows, which fasted during the weeks of giving birth and nursing, had weaned their pups, mated, and taken off for their feeding voyage, the males, with no one to fight over or mate with, have little more to do. The battles and posturing and vocalizing visitors marveled over in December, January, and February (see Episode One of Elephant Seal Tales) have petered out, and the only males left on the beach are yearlings, subadults or bulls who did not manage to mate.

Mostly, the bulls that lost out on becoming alpha males and mating, remained on the periphery of harems for as long as the cows were still there, and some managed to mate as cows were leaving for their feeding voyage. But others left the areas of the harems and wandered far afield. I saw the same solitary bull two weeks in a row far down the beach at Limantour, and he was still vocalizing though there were no males to impress or females to dominate (see Episode 3 of Elephant Seal Tales).

Here's a video of him at Limantour at the beginning of February:

Transcript

A large, dark brown elephant seal male, with a long, trunk-like proboscis lays on a sandy beach. Dune grasses and driftwood are visible in the background. Slowly he lifts his upper body, tilts his head back and vocalizes.

- Duration:

- 16.921 seconds

A 16-second-long video of an adult bull elephant seal vocalizing on Limantour Beach. Video taken on February 7, 2021.

A Weanling's Life

When the cows leave after nursing their pups for about 28 days, their weaned pups, the weanlings, are well and truly on their own but, at the beginning of March, most have still not figured out how to swim or to hunt for food. They are living off the fat they packed on during their month or so of nursing.

Although these weanlings normally top out at 300 pounds, so-called "superweanlings" or "superweaners," overachievers that have managed to nurse from two cows, can weigh as much as 600 pounds. But, according to Point Reyes Marine Biologist Sarah Codde, superweanlings are rare at Point Reyes.

As you can see from the photo to either the right (or immediately above on smaller screens), the weanlings at Chimney Rock and the Lifeboat Station are of varying sizes—and some, like the superweanling in the center of this group portrait near the Historic Lifeboat Station, are truly enormous.

After they are weaned, the weanlings remain for two to three months on the beach and, because they have not yet learned how to hunt, they continue to live off their fat as they begin to practice swimming and diving in the shallow water off the beach. When they are not practicing, the weanlings live and sleep in closely-packed pods as they complete their development before they head out to sea. According to expert pinniped scientist Burney Le Boeuf, once the weanlings get the knack of diving, even on their "very first trip to sea when the animals are only 3 ½ months old…the depth and the duration of dives are great" compared to other diving mammals. By age 2, they are diving as deeply as their adult relatives.

Descriptive Transcript

Eleven dark brown, almost black elephant seal pups are strewn about a rocky, bluff-backed beach. Several of them lift their heads intermittently to look around curiously, while others lie idle. One begins to vocalize.

- Duration:

- 10.277 seconds

A 10-second-long video of a group of weaned elephant seal pups. Video taken on February 23, 2018.

But, as the weanlings leave their closely-packed pods behind, they become mostly solitary deep-water hunters, only living in close proximity to other elephant seals when they haul out again on beaches to molt or to mate and give birth. Otherwise, they tend to remain solitary hunters.

Tagging

While the weanlings are still on land, Point Reyes National Seashore professionals tag the pups, which, as volunteer Sue Van Der Wal points out, can be a dangerous process. Volunteers are only involved in the actual tagging after extensive training and showing a long-term commitment to volunteering for the program, but volunteers can help collect data to identify the tagged seals on the beach and act as alerters for professionals like Sarah Codde.

Elephant seals tagged at Point Reyes National Seashore get pink tags attached to their hind flipper (ideally while they are sleeping). Elephant seals tagged at other locations get their own colors: for example, green tags identify elephant seals from Año Nuevo, white tags identify elephant seals from San Simeon, and orange tags identify elephant seals released by marine mammal rescue centers, such as The Marine Mammal Center. Even though elephant seals tend to return to the same beach year after year, color-coded tagging enables researchers to keep track of migration patterns.

A Life of Extremes

Elephant seals live in extremes—they feast or fast; they live either entirely in or entirely out of the water; and they lose their skin and fur in great patches during their yearly catastrophic molt. These four facets of their life cycle reflect the same pattern of their all-or-nothing behavior:

- Fasting: Males do not eat or drink at all when they are on land for the battles between males that are the run-up to the mating season and for mating itself. Females do not eat or drink at all when they are on land for giving birth, nursing, mating and impregnation.

- Feeding: But after mating and nursing and weaning, females head to the deep waters of the sea to hunt and feed deeply for a couple months. Similarly, males head off (in a different direction) to hunt and feed deeply for a few months.

- Fasting again: Then, after these couple months at sea, females return to the same beaches for molting, and they fast once again for the month or so it takes for them to shed their fur and their outer layer of skin and grow a new coat of fur. Males also return to molt, but later than females.

- Feeding again: And after the elephant seals feel comfortable in their new fur and skin, they leave their pod and head back out to sea alone to feed again until next winter's breeding season.

So, while the catastrophic molt is certainly one of the dramatic stages in an elephant seal's life, there's not much for visitors to ooh and ahh over. As docent Peggy McCutcheon notes, "watching an elephant seal molt is like watching paint dry."

Interns and Volunteers

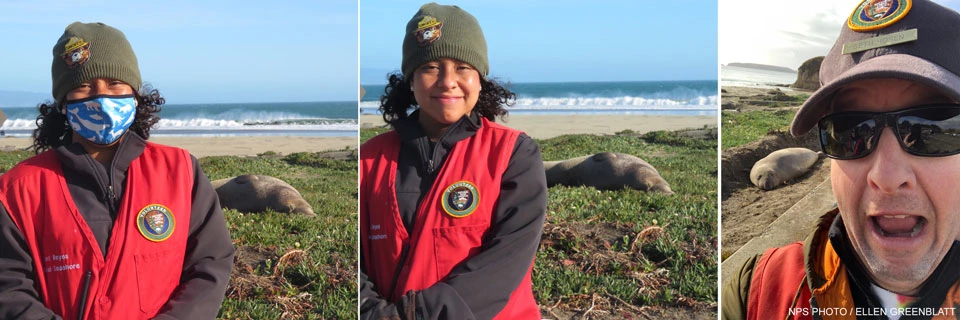

Visitors' ability to view elephant seals, before, during, and after they molt, would have been even more challenging than usual this year without the invaluable help of volunteers and interns. Interns like Ada Valencia, a graduate of Humboldt State, now on her way to a job with the Forest Service, started as a volunteer herself. She describes what she has been doing over the past months as "amazing," "rewarding," and "opening doors for younger people." Volunteers and docents echo her words. Seth Rosen, who is both a Winter Wildlife Docent and on the Point Reyes National Seashore Association Board notes, "when visitors come, they bring fresh eyes—and you get to share their fresh eyes over and over" even as you are explaining to them what is going on.

Winter Wildlife Docent Tales

To round out this final chapter of Elephant Seal Tales, adding "Winter Wildlife Docent Tales" seems essential. Some of the volunteers who help to protect northern elephant seals and educate visitors about them include:

Kendra O’Connor

A veterinarian in her working life, she drives from Sacramento to volunteer as a Winter Wildlife Docent. Even though Kendra is already knowledgeable about animals, she was "impressed by docent training, and never felt awkward," either during her training or on the job.

Jeff Wilkinson

Jeff has volunteered for more than 15 years to help educate visitors about and to protect tule elk, snowy plovers, and elephant seals, recruiting other docents along the way.

Jeff Fong

One of Jeff Wilkinson's recruits, Jeff Fong's day job is being an accountant; his wife works at the Rosie the Riveter / WWII Home Front National Historical Park. Jeff Fong noted—as did many volunteers—one of the best privileges of being a Winter Wildlife Docent: you get to stay overnight in the park at the Historic Lifeboat Station.

Keven Garcia Lopez

Kevin, who has served an internship with the Latino Heritage Internship Program and this year was lead Winter Wildlife Docent, has decided to make a career of wildlife biology and conservation after, like Intern Ada Valencia, attending Humboldt State. He’s off this summer (2021) to the Stanislaus National Forest.

And volunteers like Sue Van Der Wal, Peggy McCutcheon, Stacy Hayden, Kent Khtikian, and Linda Sudduth that readers have gotten to know in earlier chapters of Elephant Seal Tales.

After writing this series, I have applied to be a Winter Wildlife Docent, and I look forward to beginning my training this coming fall. Maybe some of you will join me!

By Ellen Greenblatt, Point Reyes National Seashore Volunteer

Please note: Disrupting behavioral patterns of seals is prohibited. Please adhere to all elephant seal protection closures, and stay at least 25 feet away from seals outside of the protection closures. Check out these seal viewing tips for more information.

Last updated: April 25, 2024