Last updated: January 29, 2022

Article

Did You Know We Never Hire Women?

In 1920, as Ranger Isabel Bassett Wasson arrived at Yellowstone, Dr. Harold C. Bryant and Dr. Loye Holmes Miller launched the new NPS education program with the Free Nature Guide Service at Yosemite National Park. Bryant described the five elements of the NPS Nature Guide Service in a March 25, 1923, St. Louis Star article as educational lectures and campfire talks, field excursions to study nature, an “office hour” to answer questions, wildflower shows, and special field trips for children. Women were as capable of conducting these duties as men and, in some cases, more so. Why, then, did so many have such difficulty getting jobs as NPS naturalists?

Training Women for Jobs They Wouldn’t Get

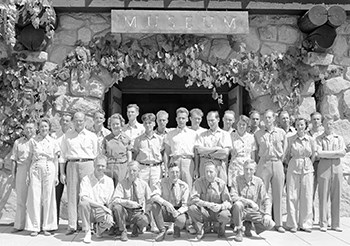

The popularity of the nature guide service at Yosemite soon resulted in other parks developing their own programs. In 1925, Dr. Bryant began the Yosemite School of Field Natural History to train nature guides, camp leaders, teachers, and park naturalists. The field school was well attended by women who comprised up to 65 percent of the students in each of the school’s first four years. Beginning in 1929, the number of women who could attend the seven-week course was capped, and by 1939 women comprised only 20 percent of the students.

Women were often rejected out of hand for naturalist positions because they “couldn’t fight fires, rescue injured rock climbers, bury dead animals, or carry out police duties”—things that were not naturalist duties. The NPS hired men who completed the field school, but rarely the women. Mabel E. Hibbard was an early exception, working as a naturalist during the 1925 summer season at Yosemite. She was probably hired because the job entailed guiding children.

A Man Is Preferable

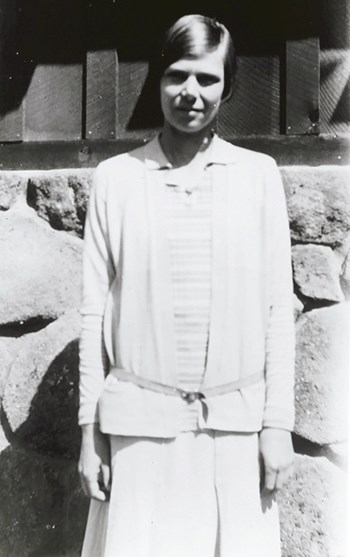

Field school graduate Ruth Ashton was actively discouraged from taking the park naturalist exam to qualify for positions. In 1928, NPS Chief Naturalist Ansel F. Hall blamed “administrative reasons imposed upon us by Washington” for not hiring women. While the NPS was actively Protecting the Ranger Image, the ranger-naturalist designation was created that same year to resolve the issue of hiring women with the park ranger title.

The second excuse the NPS used—that “suitable” housing wasn’t available—hardly seems to apply to Ashton, who already worked seasonally at Rocky Mountain National Park as an information clerk. Indeed, in April 1928 Superintendent Roger W. Toll offered her that position again for the upcoming summer, instead of the naturalist position she wanted. He even indicated he would like to have her work in the park’s museum (which he admitted didn’t exist yet!).

Toll was very outspoken in his preference for men naturalists but stated that if “we were to have a number of ranger naturalists it might work out very well to have one of them as a woman and the others men.” The general NPS bias against women as naturalists is perhaps best reflected by Toll’s comment to Ashton that “It has always been my feeling that a man was preferable for the position of park naturalist.”

In fairness to Toll, he only had one permanent and one seasonal naturalist position in 1928—and, as he told Ashton, Dr. Margaret Fuller Boos had recently applied for the seasonal position. Ashton chose to attend the field school in 1928 instead of working in the park’s information office. Edmond Rogers, Toll’s replacement, hired her back into the information office for the 1929, 1930, and 1931 seasons. She once remarked in frustration that “the best way to get into the Park Service is to marry a ranger.” Although many women did marry into the NPS, Ashton wasn’t one of them.

Although the NPS wasn’t willing to hire Ashton as a naturalist at the time, it had no problem using her botanical research. Her book, Plants of Rocky Mountain National Park, was the first comprehensive plant list of the park. It was first published by the Government Printing Office in 1933. In 1946, she finally received a very brief appointment as a naturalist at the park to work on a second edition of her book. An update to her manual completed by other authors in 2000 keeps her classic work useful even today.

The Opening Salvo

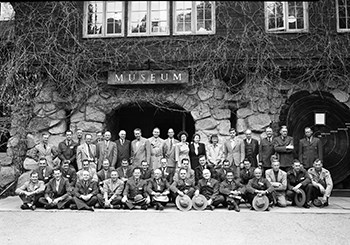

Toll was certainly not alone in expressing his opinion that women did not make good naturalists, in spite of their earlier successes at Yellowstone National Park. At the 1929 First Naturalists’ Conference, George C. Ruhle, park naturalist at Glacier National Park, shared his view of nature guide qualifications. His vision of naturalists was that they were knowledgeable scientists, as well as poets, artists, storytellers, and teachers. In addition, they needed magnetic personalities, contagious enthusiasm, courtesy, dignity, tact, levelheadedness, discretion, and good grooming. With that long list of criteria, it’s a wonder that the NPS found any naturalists at all!

Ruhle claimed that “public attitude seems to register against female guides. Even though a woman possesses a wealth of information, coupled with qualities enumerated above, she will not be as well received, will not be as successful, as the male guide.”

Ruhle’s comments try to discredit women naturalists based on public perception, rather than the personal feelings of men supervisors. He provided no support for this opinion, which is easily contradicted by the popularity of the women naturalists and the acclaim given by NPS management and the media to early women park rangers doing naturalist-type work since 1920s. Less than a year after the ranger-naturalist classification had been created to hire women without using the park ranger designation, the campaign against women naturalists had begun.

No Jobs for You, Girls

In 1939, Bert Harwell, assistant director of the school and Yosemite’s chief naturalist, blatantly told Mildred Ericson and the three other women in her class, “Nice to have you here in the school, girls, but of course there’s no jobs for you in the National Park Service.” With attitudes like these, it’s not surprising that most of The Women Naturalists who got jobs never attended the Yosemite field school.

Ericson did eventually get a seasonal naturalist position at Yellowstone National Park following World War II. She certainly had the credentials for it, as during the early 1940s she directed the nature guide service in the Minnesota state parks.

When Beatrice “Bettie” Willard completed the course in 1948 and voiced her desire to be a park naturalist, NPS Chief Naturalist John Doerr asked, “Did you realize we never hire women?” Fortunately, not everyone shared his views. Overhearing Doerr’s comment, Dorr Yeager, naturalist for the Western Region, surveyed superintendents and found four willing to hire her. This resulted in temporary ranger-naturalist positions at Crater Lake and Lava Beds National Park.

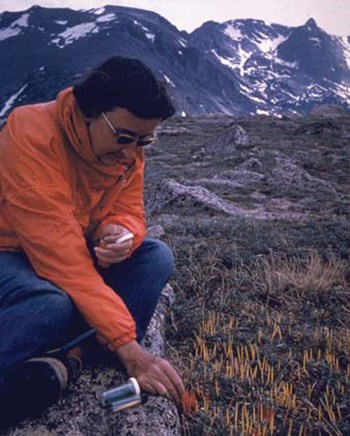

Like Ashton, Willard continued to make important contributions to the NPS even without a permanent naturalist job. In 1958, she began an alpine tundra research project at Rocky Mountain National Park, which she continued working on for the next 40 years. She went on to earn a PhD in botany in 1963 and become a world- renowned tundra ecologist. Her study plots at Rocky Mountain are the oldest permanent plots in the National Park System and some of the oldest in the world. In 2007, the Beatrice Willard Alpine Tundra Research Plots were added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Dr. Willard became one of Colorado’s environmental leaders. In addition, she was one of the women leading the successful campaign to establish Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument. She also influenced federal environmental policy. She was a key advisor to presidents Nixon and Ford and the first woman to serve on the President’s Council for Environmental Quality.

Although her efforts had broad positive impacts for the NPS and the environment as a whole, imagine what she and so many other incredibly smart and talented women would have brought to the NPS had they had the same job opportunities as men.

Pansy Pickers and Butterfly Chasers

In spite of the NPS’s reluctance to hire women naturalists, the field was traditionally associated with women—a fact that wasn’t lost on the men. Discussion at the 1940 Second Naturalists’ Conference noted that training temporary park rangers with the naturalists “tends to cut down the ridicule of the naturalists as being ‘pansy pickers and butterfly chasers.’”

Although male naturalists saw themselves as rangers with expertise in natural history, they were not always treated as such by other park rangers. Ruhle recalled the tension between rangers and naturalists during a 1977 interview. He noted that of the 11 naturalists hired at Glacier National Park in the 1930s, seven were football players who were deliberately hired to counter the “effeminate stigma attached to naturalists.” By redefining naturalists as “manly men,” the NPS excluded women from another career path, but this time one that was traditionally associated with women.

No Good Reason

In 1930, the NPS Branch of Research and Education reported that there were just six women working in ranger-naturalist and museum positions in four parks around the NPS. Even excluding seven vacant positions, there was ten times that number of men naturalists that same year.

A November 1945 letter from Carl Russell to Natt Dodge, superintendent at Mesa Verde, perhaps best sums up the NPS rationale for excluding women from naturalist jobs. In response to Dodge’s request to hire Jean Pinkley as a ranger-naturalist, he writes “There is no good reason why women should not hold park naturalist jobs; we have simply said, rather arbitrarily, that we do not favor the placement of women in these positions. As a general rule I think we are right in this.”

As a result of this arbitrary practice, most women would have to wait until the 1960s to once again be considered for uniformed positions in NPS education and interpretation.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.