Last updated: April 19, 2021

Article

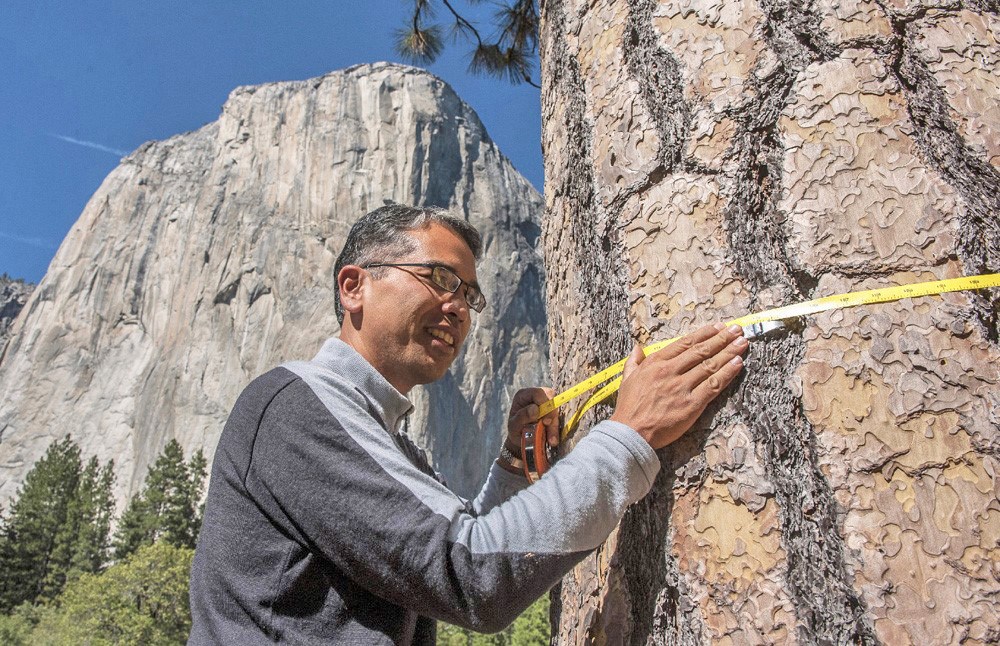

Climate Change Communication Series: Dr. Patrick Gonzalez, Principal Climate Change Scientist

By Lara Volski, Interpretive National Park Ranger

Golden Gate National Recreation Area believes in taking action now to protect our shared environment and prevent future damage. I spoke with Dr. Patrick Gonzalez in an effort to bridge the gap between science and communication, and reinforce the interdisciplinary nature of a global issue that will affect both natural ecosystems and human lives. Dr. Gonzalez is the principal climate change scientist for the National Park Service. He’s also an associate adjunct professor at UC Berkeley and a lead author on four reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the organization awarded a share of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize. My conversation with Dr. Gonzalez revealed that while climate change and its intersections with human narratives are infinitely complex, the simplest solutions are often the best antidotes for wicked problems.

Climate Change in Golden Gate and the National Park System

© Al Golub / Golub Photography

“National parks conserve some of the most irreplaceable natural and cultural sites in the world, and our actions can help protect them from human-caused climate change.”

This is a key message on climate change in national parks that Dr. Gonzalez shares with others. His message is two-fold. For one, national parks are worth conserving. This is certainly due to a variety of emotional, symbolic, social, and ecological reasons. But in terms of climate change, national parks play a fundamental role in carbon sequestration. Any ecosystem stores carbon to some extent, and national parks protect ecosystems from land use change and other industrial activities that emit carbon. Coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) ecosystems, like Golden Gate’s very own Muir Woods National Monument, can grow to store carbon at the highest known density in the world.

And secondly, our actions matter. Dr. Gonzalez’s research has demonstrated that climate change is heating the U.S. national parks at twice the rate of the country as a whole. Reducing emissions of fossil fuels can protect national parks from the most dramatic temperature increases, but Dr. Gonzalez believes that community and individual mobilization is needed to drive more systemic change.

NPS / Lara Volski

Dr. Gonzalez has described dead yir trees in Senegal as the first unmistakable sign of climate change he ever encountered. He has yet to see the impacts of climate change in the Bay Area as clearly as he did in Senegal because this West African country has experienced a steeper decrease in rainfall than anywhere else in the world. But he thinks the redwoods of Muir Woods can prompt others to act against climate change just as the yir trees motivated him.

Climate change has the potential to reduce fog, which the old-growth giants of Muir Woods need to survive. The disappearance of redwoods would not only mean the loss of a key player in carbon sequestration, but the loss of a celebrated cultural symbol. “It always moves me to think about the people of the past who had the vision to protect Muir Woods. My most inspiring moments in national parks in the Bay Area have occurred when I was appreciating the centuries of history that redwoods have survived,” Dr. Gonzalez explained. Beyond the symbolism of redwoods, Golden Gate’s status as an urban park means it has a unique role to play when it comes to addressing climate change. Dr. Gonzalez noted how Golden Gate had the highest number of visitors of any national park in 2018. A large part of this is due to its proximity to dense urban areas like San Francisco and Oakland. Dr. Gonzalez also described how numerous studies have demonstrated that green space can improve mental health, especially in urban areas. This means that Golden Gate is poised to demonstrate the benefit of land protection to many people. In addition, urban national parks play a key role when it comes to addressing climate change as well, as green space in metropolitan areas can reduce the urban heat island effect. Parks situated at the boundaries of the boundaries of urban and wild areas can thus actively reduce the effects of climate change while enabling climate change communicators to reach more people.

Communicating Climate Change

Climate change communicators often struggle to identify their target audience. The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication has identified climate change’s six Americas: the Alarmed, the Concerned, the Cautious, the Disengaged, the Doubtful, and the Dismissive. “What I think is behind this question of [a target audience] is efficiency of effort and the possibility of a greater impact by focusing on some people over others,” Dr. Gonzalez said. “But I’m an idealist – I would like to see the National Park Service communicate to all six Americas, ranging from people who are deniers to those who want to act and everyone in-between.”

NPS

Behind this sentiment is the idea that communicators need to be generalists. Dr. Gonzalez reflected on a campfire talk he gave at Joshua Tree National Park. He smiled as he described the desert in January and the faces lit around the fire. “It was a lot of fun,” he said. “In that moment, I remembered when I was the kid listening to the ranger.” Climate change communicators can be specific about the audiences they pursue, but interpreting the value of national parks is ultimately about connecting with all people and working together to decipher the value of our shared environment. In other words, communicators should be able to learn as much from their audience as their audience learns from them.

Working together will mean acknowledging that climate change is just as much of a human and social issue as it is an environmental one. Upon discussing how we should approach climate change communication in conjunction with environmental justice, Dr. Gonzalez described how a lot of published research has demonstrated that disadvantaged communities are at risk of being exposed to more severe climate change impacts. This trend is already well recognized for conventional air pollution, and Bay Area examples of this exist within communities that live near the Richmond Refinery or in West Oakland. Many of the people who live in the areas that are more impacted by pollution are people of color, primarily Black people, and a large part of this is due to intentional forms of segregation such as redlining. An example of how this social trend will interact with climate change is the impact that sea level rise will have on Bayview-Hunters Point in San Francisco. It is important to ensure that all communities, and especially communities of color, are equipped to participate in climate change and sustainability action. Communicators can help by highlighting environmental justice and emphasizing the unequal impacts of climate change.

Looking Toward the Future

NPS / Lara Volski

When it comes to finding solutions to climate change, individual sustainable actions are often pitted against large, community-wide changes. When asked which ones we should prioritize, Dr. Gonzalez’s answer was simple, “It’s both! Communal actions are the sum of individual actions. The fundamental challenge is engaging as many people as possible.” According to Dr. Gonzalez, it’s already clear that community organizing can engage more people and produce more progress than working with people one-by-one. But the solution ultimately won’t succeed if each individual doesn’t do their part.

That being said, some solution-seekers say that climate change advocacy should focus more on corporations and less on individuals. In Dr. Gonzalez’s view, corporations serve individuals, and exist to meet the expressed wishes of the people purchasing their products. For example, responsibility falls on the people who purchase cars just as much as it falls on car producers. Dr. Gonzalez personally bypasses this conundrum by not owning a car at all. On days when the 76X bus doesn’t stop in the Marin Headlands, he will still take a bus to the end of the Golden Gate Bridge and then hike over four miles to Fort Cronkhite. Dr. Gonzalez does this with the knowledge that through our consumption of materials, we are ultimately responsible for fossil fuel emissions, and corporations are simply the medium by which that occurs in our society.

Of course, this medium can be changed if we work as a community to rethink the system that provides services. Dr. Gonzalez continued to use transportation as an example. Corporations can make incremental improvements to vehicles in response to a growing demand for sustainability, but what we must ultimately realize is that the required service is simply getting from one place to another. Providinge that service through other means, such as more accessible public transportation, is a way of rethinking the system in place.

In this way, Dr. Gonzalez believes that “the simplest solutions are the most exciting.” He views the energizing nature of simple solutions as partly due to climate change’s complexity. Many of the engineering efforts put forth to address climate change strike Dr. Gonzalez as extreme. He believes it would be a lot easier to simply not burn fossil fuels in the first place than to design elaborate ways to capture carbon that has already been released. By rethinking the system, we can avoid the complex measures it takes to undo the impacts humans have had on our environment, our planet, and each other.

Ultimately, Dr. Gonzalez feels great hope when he looks forward to Golden Gate’s future as climate change progresses. Dr. Gonzalez sees the solar panels on Alcatraz Island and the LEED Platinum certified buildings throughout the park as examples of the substantial progress Golden Gate has made. At the same time, Dr. Gonzalez’s research has revealed that Golden Gate and the Bay Area at large has already been subjected to sea level rise, bird range shifts, increased sea surface temperature, and ocean acidification due to human caused climate change. We will need to continue prioritizing solutions in order to lessen these impacts.

Bonus: Advice for Aspiring Climate Change Scientists

Rhonie Roggers (2018)

“The most important characteristic of a climate change scientist is wanting to make a meaningful change in the world,” Dr. Gonzalez said. He went on to explain how climate change science is not a narrow discipline. Rather, it is a broad scientific endeavor directed at conserving nature and human wellbeing for future generations. Its goal of solving a global problem requires an interdisciplinary approach.

But aspiring climate change scientists shouldn’t necessarily try to be generalists. They should instead aim to become an expert in one particular aspect of climate change, then incorporate many disciplines when addressing that aspect. For example, Dr. Gonzalez is a forest ecologist, but he’s relied on fields such as anthropology, energy, policy, and even the arts in order to fully address how climate change will affect forests.

“With internal motivation and a desire to change the world,” Dr. Gonzalez concluded, “I am confident that any young or aspiring climate change scientist can make a meaningful difference.”

Works Cited

Gonzalez, P., F. Wang, M. Notaro, D.J. Vimont, and J.W. Williams. 2018. Disproportionate magnitude of climate change in United States national parks. Environ. Res. Lett. 13(10), doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aade09.

Gonzalez, P. 2016. Climate change in the National Parks of the San Francisco Bay Area, California, USA. Berkeley, CA: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

Green, M. 2016. How Government Redlining Maps Pushed Segregation in California Cities [Interactive]. KQED: The Lowdown.

Green Action. Climate Change and Sea Level Rise: Impacts on Bayview Hunters Point.

National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Reclaims Highest Annual Visitation in 2018.”

National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Green Buildings.

National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Sustainable Alcatraz.

Roy, J., P. Tschakert, H. Waisman, S. Abdul Halim, P. Antwi-Agyei, P. Dasgupta, B. Hayward, M. Kanninen, D. Liverman, C. Okereke, P.F. Pinho, K. Riahi, and A.G. Suarez Rodriguez, 2018: Sustainable Development, Poverty Eradication and Reducing Inequalities. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. In Press.

Shogren, E. 2016. Meet the Man Helping the Park Service Prepare for a Hotter Future. High Country News – Know the West.

United States Environment Protection Agency, U.S. Department of the Interior. Reduce Urban Heat Island Effect.

USGS. What Is Carbon Sequestration?

Van Pelt, R., S.C. Sillett, W.A. Kruse, J.A. Freund, and R.D. Kramer. 2016. Emergent crowns and light-use complementarity lead to global maximum biomass and leaf area in Sequoia sempervirens forests. Forest Ecology and Management 375(1): 279 – 308.

Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Global Warming’s Six Americas.