Last updated: January 5, 2026

Article

Boston's Women and the Underground Railroad

Occupying a nearly mythological status in US History, the Underground Railroad operated as an informal but intricate network of safe houses from slaveholding states in the American South to free states in the American North and Canada.[1] Comprised of both Black and White abolitionists, members of this secret network typically did not know the names of other safe house operators that were located more than two or three towns away from their own safe house.[2]

Traditional definitions of the Underground Railroad characterize it as a network of safe houses leading out of enslavement in the South to freedom in the North. Those escaping enslavement worked their way covertly and deliberately along that network until they reached a free state, thereby becoming a free person. Traditionally, contributions to the Underground Railroad often only include direct work to help freedom seekers, such as operating a safe house.[3]

However, in the first half of the 1800s, the Underground Railroad evolved from a system of aid for freedom seekers, to an intricate, nationwide network of activists determined to aid freedom seekers and defy state and federal laws perceived as unjust. In the decades leading up to the American Civil War, Boston's women stood at the center of this complex network, acting as critical contributors to the Underground Railroad by bearing witness to the effects of slavery, participating in and founding anti-slavery organizations, and providing direct aid to freedom seekers.

-

Boston's Women and the Underground Railroad Introduction

This video explores Nancy Prince’s 1847 confrontation with the slave catcher Woodfork and serves as an introduction to the critical contributions of Boston’s women to the Underground Railroad.

- Duration:

- 1 minute, 13 seconds

Caroline Healey Dall, Journal, October 20, 1850, microfilm, reel 34, Dall Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Bearing Witness

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, Boston's women bore witness to countless events related to the Underground Railroad. These women experienced firsthand the triumphs and failures of Boston's abolitionist community. As they processed and reflected on these events, the women often recorded their thoughts and emotions, as well as reactions and emotions of Boston's citizenry, in journals or private letters to friends and family. Many of these documents later entered public archives, preserving a public record of women's involvement with the Underground Railroad. On October 14, 1850, abolitionist Caroline Dall attended an anti-Fugitive Slave Law meeting at Faneuil Hall. She recorded the experience in her journal, writing, "I could not resist going to the meeting at Faneuil Hall in the evening. It was a grand meeting. There was but one feeling among the 6000 persons assembled there, and that was to trample this law under foot."[4] The presence of these women as witnesses and participants, and their carefully curated records, are central to understanding the operation and impact of the Underground Railroad in Boston.

-

Boston's Women and the Underground Railroad: Witness and Testimony

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, Boston's women bore witness to the triumphs and failures of the Underground Railroad in Boston. The accounts these women recorded offer important testimony on the events and the reactions of Boston's citizenry.

- Duration:

- 1 minute, 55 seconds

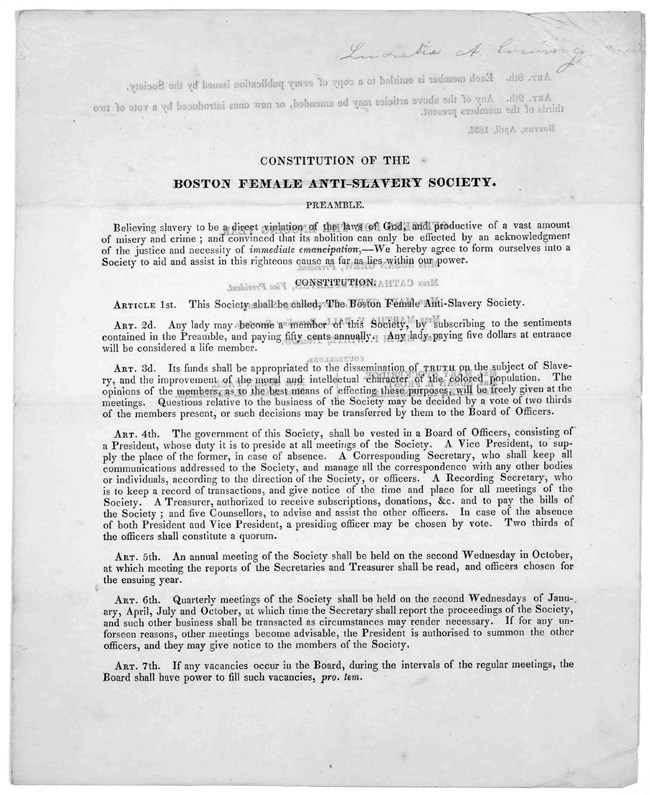

Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. (1834) Constitution of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Boston. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress

Organizing

Women also contributed more publicly through abolitionist organizations. When sexism and societal norms failed to grant women access to certain abolitionist societies, they created their own, recruiting individuals and other organizations open to collaborating with women. During the thirty years preceding the Civil War, Boston's women joined, founded, and collaborated with numerous societies that allowed them to contribute to the Underground Railroad, including: the Afric-American Female Intelligence Society;[5] the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society;[6] the New England Freedom Association;[7] the Boston Vigilance Committee;[8] and the Fugitive's Aid Society.[9] These organizations raised critical funds to support the Underground Railroad and empowered Boston's women to provide aid to the freedom seekers entering their city.

-

Boston's Women and the Underground Railroad: Organizing

Beginning in the 1830s, Boston's women joined and founded anti-slavery organizations that allowed them to contribute to the success of the Underground Railroad.

- Duration:

- 1 minute, 40 seconds

Cleveland Gazette, February 24, 1894.

Direct Aid

Organizations such as the Boston Vigilance Committee also capitalized on the unique position Black women occupied in society, using it to enable the rescue of freedom seekers stowed away on ships in Boston Harbor. When ships suspected of carrying stowaways arrived, they were often met by a "Committee of Reception," which stood ready with food and clothing, and provided a carriage to transport freedom seekers north of the Canadian border. Black women served as critical members of these "Committees of Reception" since Captains rarely perceived them as threats. As abolitionist minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson recalled, "The practice was to take along a colored woman with fresh fruit, pies, &c – she easily got on board & when there, usually found out if there was any fugitive on board; then he was sometimes taken away by night."[10]

Other freedom seekers arrived in Boston and remained, for a period of time, at safe houses scattered throughout the city. Women excelled as safe houses operators, providing food, clothing, orientation to the city, and a place of refuge. Women such as Harriet Hayden and Clara Vaught routinely welcomed freedom seekers into their homes, later receiving reimbursement for their expenses by the Boston Vigilance Committee.[11]

-

Boston's Women and the Underground Railroad: Direct Action

In the 1840s and 1850s, many of Boston's women operated their homes as safe houses on the Underground Railroad, risking their own safety and freedom to provide direct aid to freedom seekers.

- Duration:

- 2 minutes, 22 seconds

Remembering Their Stories

The selfless determination of these women to aid freedom seekers, whether by attending major anti-slavery events, founding anti-slavery organizations, or welcoming strangers into their home, forever changed the landscape of the Underground Railroad in Boston and the United States.

-

Boston's Women and the Underground Railroad: Elevating Their Contributions

This video recognizes the many Boston women who contributed to the Underground Railroad and acknowledges the work that still remains to identify all women.

- Duration:

- 1 minute, 24 seconds

Footnotes

[1] Raymond Bial, The Underground Railroad (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995), 8.

[2] Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement (New York: Amistad, 2006), 206.

[3] Bial, The Underground, 8.

[4] Caroline Healey Dall, Journal, October 20, 1850, microfilm, reel 34, Dall Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[5] “Constitution of the Afric-American Female Intelligence Society of Boston,” The Liberator, January 7, 1832, 2.

[6] Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. (1834) Constitution of the Boston Female anti-slavery society. Boston. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.05600700/.

[7] "New-England Freedom Association," The Liberator, December 12, 1845. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers (accessed August 28, 2020).

[8] The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston (Marlboro, NH: The Chalet Underhill Farm, 1851).

[9] “A Benevolent Object,” The Liberator, October 10, 1862.

[10] Sandra Harbert Petrulionis, "Fugitive Slave-Running on the Moby Dick: Captain Austin Bearse and the Abolitionist Crusade," Resources for American Literary Study 28 (2003): 69.

[11] The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston (Marlboro, NH: The Chalet Underhill Farm, 1851), 24; The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Account Book, 8; Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom; Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829 - 1889 (New York City: Penguin Books, 2013), 189; Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement (New York: Amistad, 2006), 369.

Video Credits

Introduction Video: Images courtesy of Digital Commonwealth, the Library of Congress, and the Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Witness and Testimony Video: Images courtesy of the Library of Congress, the American Antiquarian Society, and Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Organizing Video: Images courtesy of Historic New England, the Library of Congress, Boston Public Library, and the U.S. Capitol.

Direct Action Video: Images courtesy of the National Museum of American History, Massachusetts Historical Society, the Library of Congress, the Ohio Memory Center, the Cleveland Gazette, and Archive.org.