Last updated: February 18, 2026

Article

Mystery of the Lost "Battle of Bunker Hill Cyclorama"

Scientific American, 1886, v55. Ohio State University.

What is a Cyclorama?

As one of the most pivotal and mythologized moments in early American history, the Battle of Bunker Hill has inspired generations of artists for more than two centuries. Undoubtedly, the most ambitious and monumental work of art dedicated to the events of June 17, 1775, was "The Battle of Bunker Hill Cyclorama." It went on display in Boston in early 1888, yet today it is now mysteriously lost.

In an era before IMAX blockbusters or even primitive motion pictures, audiences in the late 1800 and early 1900s attended immersive experiences by visiting cycloramas. A cyclorama ("circle view" in Greek) generally consisted of a painting displayed within an enormous circular structure, presenting viewers with a 360-degree view. These paintings were hundreds of feet long and could cost $200,000, taking a team of artists a year and a half to complete.

The invention of the cyclorama is credited to Irish painter Robert Baker, who painted landscapes in the late 1700s. In time, historical events, particularly battles, replaced rural and urban landscapes as popular cyclorama topics. Cycloramas, like many other varieties of entertainment in the 1800s, often toured from city to city. Each locale displayed these paintings in massive cyclorama buildings, impressive pieces of architectural craftmanship themselves, featuring crenelated entrances and domed rotundas.

For paying attendees, the immersive experience began by entering the cyclorama building through a darkened, narrow passageway. After ascending a central staircase, visitors emerged onto a viewing platform, encircled by the immense cyclorama. For visitors it was as though being located within the painting itself. The use of narrators, lighting, and musical instruments frequently heightened the spectacle's drama. Three-dimensional objects or figures were often seamlessly blended into the painted backdrop as well.

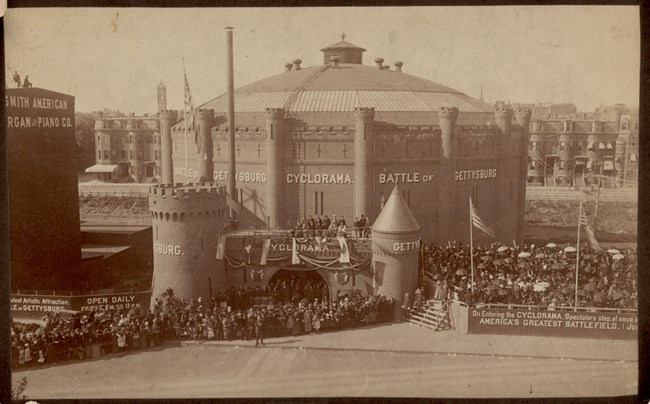

"Cyclorama building. Battle of Gettysburg. Tremont Street," ca. 1884-1889. Boston Public Library.

Boston's Cyclorama Buildings

In the 1880s, Boston was a large enough city to host two cyclorama venues. Designed in 1884 by the Cummings and Sears architectural firm, Boston's Cyclorama Building displayed "The Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama," painted by French artist Paul Dominique Philippoteaux. The dome of the building was one of the largest unsupported domes in the world at that time. The building, located on Tremont Street in Boston's South End, still stands today, although it no longer displays monumental works of art.

A few years later in 1887, the same architectural firm constructed a second cyclorama building only two blocks away, also on Tremont Street. Both sites were owned by the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, an organization formed by Union military officers in the aftermath of the American Civil War. This new structure (practically identical to the first cyclorama building) opened on February 5, 1888, displaying "The Battle of Bunker Hill Cyclorama."

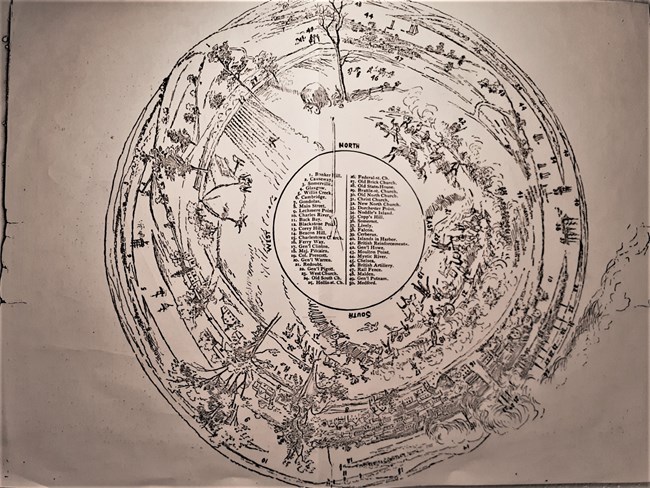

"A brief account of the Battle of Bunker Hill." Princeton University.

Revolutionary Spaces

According to contemporary accounts the cyclorama's canvas measured 400 feet long and 50 feet tall, an alleged half an acre of painted surface, which was similar to the dimensions of the Gettysburg Cyclorama (however, the painting may well indeed have been far smaller, perhaps only 240 feet long and 18 feet tall). Leonard Kowalsky supervised the painting.[1] Kowalsky worked with a team of artists including Gerard Picard, V. Coppenolle, and George Bellenger, all graduates of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The cyclorama depicted the third and final British assault on the colonial fortifications on Breed's Hill from the perspective of the redoubt. The cyclorama's audience would be virtually surrounded by the bitter hand-to-hand combat. The painting also displayed views towards Bunker Hill to the west and Boston to the south.

To make sense of this all, visitors to the cyclorama received a 16-page brochure describing the events of the battle, as well as a circular key annotating individual figures or locations within the painting.

A few months after opening this new cyclorama, a visitor remarked in a letter to his son; "I also went to the panorama of the battle of Bunker Hill which is as good as that of Gettysburg…It makes you feel just as if you lived there."[2]

The Cambridge Press News agreed, writing that, "the new cyclorama…has been pronounced by press and public one of the most perfect illusions and most remarkable works of art which has been shown in this country for many years."[3]

The Cyclorama Goes Missing

For all its acclaim, "The Bunker Hill Cyclorama" was only displayed for two years. After 1890, other cycloramas depicting the life of Christ and the Battle of the Little Bighorn took its place. Ironically, as cycloramas reached their height of artistic accomplishment, they also quickly fell out of public favor. Much of the appeal derived from their novelty for first-time visitors, which did not bear up after repeated viewings. By the early 1900s, many cycloramas fell to neglect and disrepair. "The Battle of Bunker Hill Cyclorama" building itself was remodeled in 1895 and became the Castle Square Theater (demolished in 1933).

Lacking a suitable place to be displayed, the exact fate of the cyclorama painting after 1890 remains unknown. It may have been buried beneath Boylston Street and then, allegedly, subjected to the ravages of curious children and stray dogs. Others conjectured that it was packaged up and sent to a freight storage area at South Station. "The Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama" fortunately enjoyed a happier fate. It is currently located at Gettysburg National Military Park.

Revolutionary Spaces

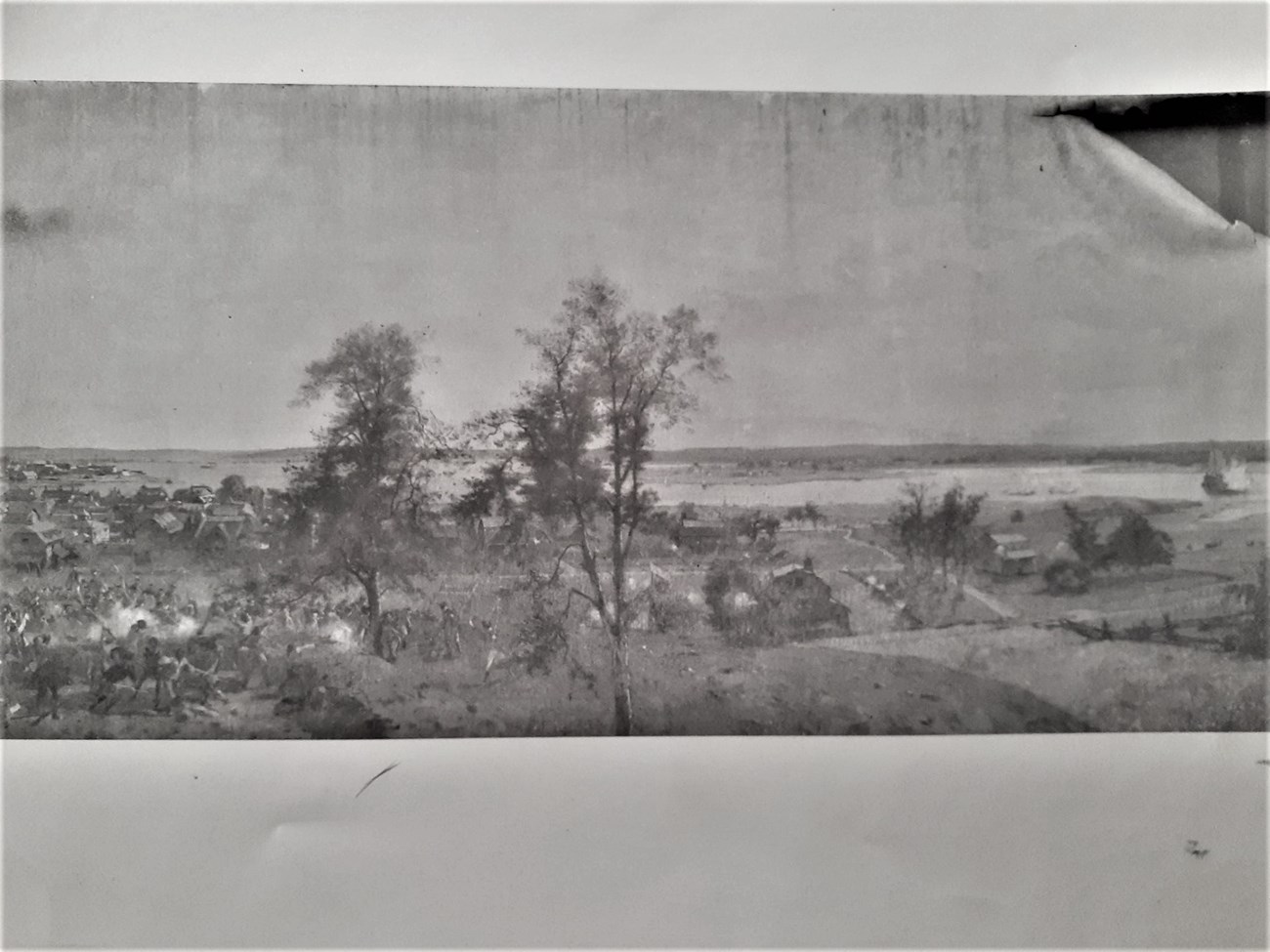

Later, nearly half a century since the "Battle of Bunker Hill Cyclorama" went missing, interest in it increased in 1943 when the Bostonian Society (now Revolutionary Spaces) procured photographic negatives of the original cyclorama. A reproduction of the lost cyclorama based on the negatives was considered, which no doubt would have delighted older Bostonians who had been alive when the "Battle of Bunker Hill Cyclorama" first opened. However, no such reproduction was ever undertaken.

Decades later in 1961, Clifford Smith donated three oil on canvas studies of "The Battle of Bunker Hill Cyclorama" to the Bostonian Society. Kowalsky painted the studies in 1883 to be used as reference material when composing the full cyclorama. These paintings were themselves sizable pieces of artwork, measuring four feet in height by 10 feet in length. The studies had once adorned the walls of a chalet in Rockport, Maine, owned by Smith's uncle. Sadly, all three studies had sustained both water and fire damage, and a fourth study was completely burned. As a result, the studies only represented three quarters of the view of the original cyclorama. Nonetheless, according to a 1961 newspaper article, "Experts who have studied the sketches say they are the best representative of the historic battle they have ever seen…"[4]

Revolutionary Spaces

Interest was reignited again in the 1960s and 1970s in re-creating the original cyclorama experience by exhibiting the three surviving studies. However, the studies were in no condition to be displayed. Without funding to restore them, the Bostonian Society stored them in the attic of the Old State House. The Society eventually loaned the studies to the National Park Service in the 1980s with the intent of repairing them. The cost of refurbishing the paintings was substantial however, and the Park only restored one of the three paintings. Boston National Historical Park considered displaying this sole restored study at the Bunker Hill Museum when the museum opened in 2007.

Sadly, park officials deemed it too risky to stretch the painting across the curved exhibit displays (a photo of part of this restored study can be found on the museum's second floor). For a few years the studies were kept in the Charlestown ropewalk building (with no climate control!), before they were eventually returned to the Bostonian Society, and are now kept in an offsite storage location.

Revolutionary Spaces

NPS Photo/Boyce

The Cyclorama Re-Imagined

Currently, the closest complete representation of the original cyclorama on display is a 360-degree mural displayed at the Bunker Hill Museum. Local artist John Coles painted this mural, and although not to the scale of the original cyclorama, it is nonetheless 80 feet long and four and a half feet tall. Like the original cyclorama, the mural positions the viewer in the center of the action at the redoubt. Coles worked on the mural in eleven separate sections in his studio before it was installed at the museum. From start to finish, the work took a year to complete.

"What was I thinking?" Coles later wondered when asked about accepting the painting challenge. "It was a big commission for me! I can't believe I took on the job. I'm glad I did. Some of the history was amazing."[5]

Coles used the surviving cyclorama studies and other photographs to complete his mural. He also took input from National Park Service historians, especially when detailing the combatants' clothing, weapons, and gear. Additionally, Coles ensured that representation was made of the estimated 120 Patriots of color of both African and Indigenous descent who participated in the battle, a detail not apparent in the original cyclorama. Coles further included his own face among the combatants, as well as the faces of his children and neighbors.

Incredibly, despite the relatively brief time it was seen by the public more than a century ago, the legacy of the original "Battle of Bunker Hill Cyclorama" continues to enchant historians, art lovers, and detectives of lost media. Today, faded brochures, old articles, incomplete photos, handfuls of eyewitness reports, and scaled reproductions can only offer us a hint at what thrilled awe-struck patrons in the late 1800s.

Footnotes

[1] Conceivably Leonard Kowalsky and German-born French painter Leopold Kowalski are the same person. The spelling of “Kowalsky” likely is a 19th Century misattribution.

[2] "Letter to William James from his father," April 29, 1888, Revolutionary Spaces Archives.

[3] Laura Lee Schmidt, editor and curator, et al., "Having Fun," Building Blocks: Boston Stories from Urban Atlases (Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library, 2022). https://www.leventhalmap.org/digital-exhibitions/building-blocks/topics/having-fun/.

[4] Christian Science Monitor, June 17, 1961, Revolutionary Spaces Archives.

[5] Interview with John Coles, May 4, 2023.

Sources

Browne, Patrick. "The Boston/Gettysburg Cyclorama Painting," Historical Digression, August 8, 2013, https://historicaldigression.com/2013/08/08/the-bostongettysburg-cyclorama-painting/.

"Bunker Hill Cyclorama Sketches paintings," Revolutionary Spaces, Online Collections, https://revolutionaryspaces.catalogaccess.com/objects/2018.

"Cyclorama Painting," Gettysburg National Military Park, September 22, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/gett/learn/historyculture/cyclorama.htm.

Illustrated Boston, the Metropolis of New England. New York, American Publishing and Engraving Co., 1889.

Schmidt, Laura Lee. "Having Fun," Building Blocks: Boston Stories from Urban Atlases, 2022, https://www.leventhalmap.org/digital-exhibitions/building-blocks/topics/having-fun/.

Wray, Suzanne. "A Tale of Two Cycloramas," The National Park Service, May 21, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/a-tale-of-two-cycloramas.htm.