Last updated: January 18, 2024

Article

A Tale of Two Cycloramas

Article from the proceedings from Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

A Tale of Two Survivors: The Gettysburg and Atlanta Cycloramas

By Suzanne Wray

Abstract

In the nineteenth century, the painted panorama allowed viewers to immerse themselves in another world, be it a city or a battlefield. The purpose-built building in which the realistic circular painting was housed was part of the apparatus needed to create the desired illusion: viewers saw the painting from a circular platform, and a three-dimensional foreground helped disguise the point at which the painting ended and the foreground began. By the late 1800s, the size of paintings and buildings had been standardized, enabling panoramas to be exchanged between cities.

In the United States, the panorama was often called a “cyclorama” and paintings of Civil War battles became the most popular subjects. Large cities often held more than one panorama rotunda and competed for an audience, while studios in Mott Haven, New York, Milwaukee, and Englewood, Illinois turned out the large canvases.

As the popularity of the panorama waned, buildings were demolished or renovated to serve other purposes, and cyclorama paintings often disappeared into storage, or were destroyed. Or they were shown in other settings: hung around the walls of a skating rink or even a department store, the illusion of “being there” was lost. Worlds’ Fairs and similar exhibitions often had a cyclorama on display, thus keeping them on display long after they had disappeared from most cities.

Changing ideas about how a battle or battlefield should be presented to the public also changed ideas about the buildings in which the cycloramas were housed, and how they were shown. Both the Gettysburg Cyclorama and the Atlanta Cyclorama were improperly hung and the paintings deteriorated; misguided preservation attempts often did more damage.

Both the Gettysburg and Atlanta Cycloramas have survived: the Gettysburg painting was recently restored and is housed in a new building on the battlefield; the Atlanta Cyclorama is being moved to a new building and will be restored. Tourists today, living in an age where virtual reality is often spoken about, now can experience one of its precursors: the cyclorama.

Boardman Collection/Atlanta History Center

Panoramas

Long before the term “virtual reality” was coined, tourists were visiting other cities, or seeing battles by entering a circular building to be immersed in another world-in the form of a 360-degree painting. “Virtual travel” was appealing to viewers; one wrote in 1824: “Panoramas are among the happiest contrivances for saving time and expense in this age of contrivances. What cost a couple of hundred pounds and half a year half a century ago, now costs a shilling and a quarter of an hour.” The panorama allowed the viewer to avoid “the innumerable miseries of travel, the insolence of public functionaries, the roguery of innkeepers, the visitations of banditti…and the rascality of the custom-house officers…” [1]

“Panoramas became the newsreels of the Napoleonic era,” wrote Richard Altick in The Shows of London.[2] A panorama rotunda had just been established in Leicester Square when the war with France broke out: newspapers could report on current events, but could not illustrate them. Panorama painters produced representations of recent battles as quickly as possible, and they drew such large audiences that some viewers complained that the crowds on the viewing platform made it impossible to get a view of the picture in its entirety.

Why "panorama" and not “cyclorama”?

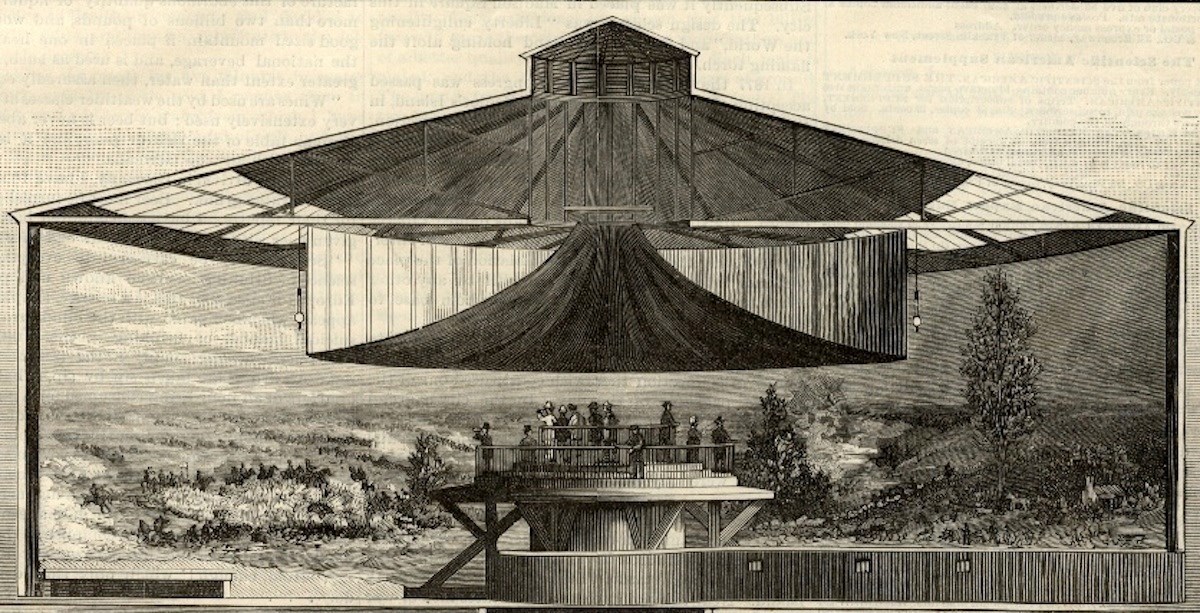

On June 18, 1787, an Irish artist named Robert Barker (1739-1806) patented a new art form: a circular painting that surrounded the viewer. Visitors entered the circular or 16-sided building, walked through a dimly lit corridor, and climbed a spiral staircase to enter upon a circular viewing platform.

Boardman Collection/Atlanta History Center

A painting, done as realistically as possible, surrounded them. The viewing platform kept the viewer at the proper distance from the painting-too close, or too far away, and the illusion would be lost-and hid the bottom of the painting. A foreground of three-dimensional objects, called the “faux terrain” or "diorama" was usually added, making it difficult for the viewer to tell where the foreground ended, and the painting began. The top of the painting was hidden by an umbrella-shaped "vellum" hanging from the roof; this also hid the skylights that admitted light to the building. Light was reflected from the painting and appeared to come from the painting itself. The viewer was cut off from any reference to the outside world and was immersed in the scene that surrounded him.[3]

It was 1792 before one of Barker's paintings was a success. By then a new word had been coined for his invention: the Greek words PAN (all) and HORMA (view) combined to form "panorama", the "all-encompassing view." The following year Barker leased a lot on Leicester Square in London and erected the first permanent panorama rotunda, a two-level hall in which two paintings could be shown simultaneously, a smaller painting shown on a level above the larger one. The building is still there, now a Catholic church.

Some of these early panoramas were brought to the United States, but interest waned in the 1850s.

The word “panorama” had quickly entered the English language. In America, it was applied to the moving panorama, which, like the circular panorama, began in Europe, but achieved its greatest popularity in America.[4] The moving panorama was literally a "moving picture," a painting that unrolled from one roller onto another in front of an audience, usually to musical accompaniment and the voice of a narrator. Moving panoramas could be painted quickly on muslin (not canvas) in distemper paint (not oil), transported by horse and wagon, canal boat, or railroad, and set up and shown in a rented hall or a schoolhouse. A man named John Banvard achieved a huge success by scrolling a painting (said to be three miles long-an exaggeration, of course) of the Mississippi River in front of audiences in America and Europe, where he gave a command performance to Queen Victoria and family. This spawned a huge number of moving panoramas: scene painters, house and sign painters created panoramas, many of them very bad, hoping to make their fortune. Newspapers and magazines printed jokes about these "distempered daubs." Charles Dickens was quoted as saying, “I systematically shun pictorial entertainment on rollers.”[5]

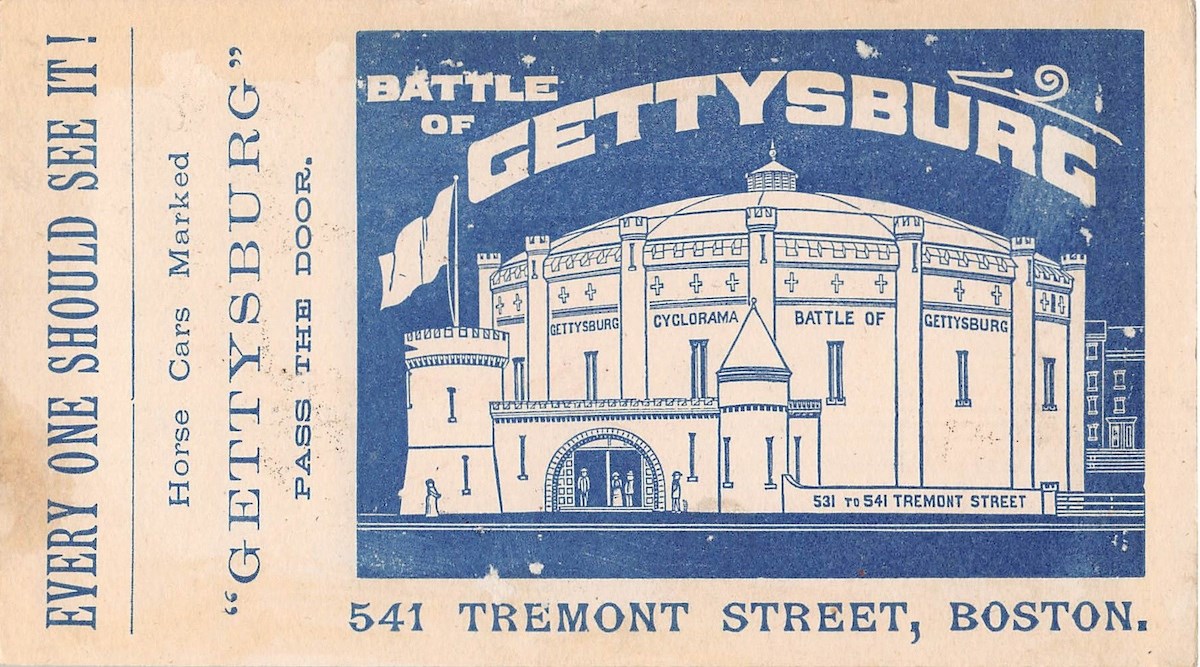

No wonder, then, when the circular panorama enjoyed a great revival in America in the late 1800s, promoters advertised them as "NOT a panorama", but a realistic painting, done on Belgian canvas and in oil paint by trained artists at great cost, and shown in a special building constructed at great cost: a work of fine art. Thus, the term "cyclorama" came into use to differentiate the circular panorama from the moving panorama. The first panoramas of this "revival" period were brought to New York by French and Belgian companies; most were panoramas showing European battles and were not terribly successful. Then, in 1883, the Belgian panorama company began preparations to install the Battle of Gettysburg in Chicago.

Paul Philippoteaux’s Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama depicts “Pickett’s Charge,” a decisive action in a decisive battle of the American Civil War, a battle that came to be known as “the turning point” of the War, the “High Tide of the Confederacy.” The three-day battle was fought on July 1, 2, & 3d in 1863 in the fields of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and claimed fifty-one thousand casualties. The victory for the Union-the Northern states-after many losses in earlier battles-drove the Confederate troops southward, lessening the perceived danger of Southern attacks on Northern cities. Even at the time, the battle was recognized as being of great importance.

The panorama of the Battle of Gettysburg also represented a “turning point” of sorts to the panoramic art form in America. In Paris and Belgium panorama consortiums were already producing paintings of a standard size, 50 feet high by 400 feet in circumference, on an almost industrial scale of production. These were intended to be moved from one rotunda to another and exchanged between cities. Once a painting was installed, stock was sold, and for many years the stockholders received a very good return on their investment. With the huge success-and profits-of Gettysburg in Chicago, paintings of Civil War battles became the most popular "cycloramas" in America. "For twenty years after the end of the war in 1865, most Union veterans were pre-occupied with their young families and new businesses, not on revisiting their recent (and sometimes traumatic) wartime experiences. This period of historical ‘hibernation’ came to an end in the 1880s with a revival of popular interest in the war.” [6] Panorama studios were established in Mott Haven, New York, Englewood, Illinois, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, by competing companies. Gettysburg was still drawing visitors in Chicago in 1893, ten years after it first opened. Supposedly over two million people saw the painting, and stockholders were paid about $25,000 a year in dividends during that time. "No other picture ever so completely captured popular fancy." 7 Tourists visiting Chicago were urged to see the cyclorama; railroads organized special excursions (advertised in local newspapers by the cyclorama companies) to bring trainloads of people into the city for a day, a day that included a visit to the cyclorama. This practice was followed in other areas, for generally a location in a large city was necessary for a panorama to be profitable. In addition, there were many versions of the Battle of Gettysburg painted, many deliberately (and incorrectly) attributed to Philippoteaux; certainly, many were not the standard "cyclorama" size, and some were probably not even circular in form. It was very common to find a Battle of Gettysburg shown at a regional agricultural fair or in a skating rink in a smaller city.

Boardman Collection/Atlanta History Center

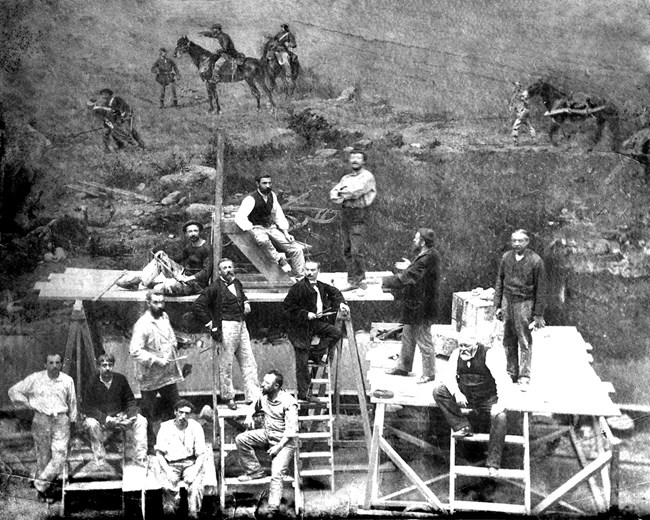

When the artists returned to the studio, a 1/10 scale painting of the finished work was created. This was transferred onto paper in pen and ink, and a grid drawn over it, with each section designated by a number and letter. The artists then transferred the image from each square onto the huge canvas, which consisted of sections of linen woven on Belgian carpet looms and seamed together. The canvas was hung from an iron ring or circular beam and attached to a weighted iron ring at the bottom. This gave the painting a hyperbolic shape, with the center of the painting somewhat closer to the viewer than the top or bottom. The painting was done in high quality oil paint by artists who stood on a movable scaffold mounted on rails; they were specialists in landscape, horses, figures, portraits, all working together under the guidance of the head painter.

Boardman Collection/Atlanta History Center

The other Gettysburg cycloramas were to be shown in Boston, Philadelphia and New York. Philippoteaux was recruited to come to America by Charles Willoughby (1838-1919), a successful Chicago clothing merchant, and Edward Brandus (1857-1939), a French art dealer who became Philippoteaux's business partner. Brandus set up a circular wooden studio in Mott Haven, in the Bronx, for the production of panoramas, thus avoiding the high duty on imported paintings. The New York painting was first shown in Brooklyn, then a separate city, in a portable iron rotunda had been constructed in Philadelphia especially for the "nomadic career" planned for it. 8 After months in Brooklyn, the building and painting were moved to New York, and installed at 19th Street and Fourth Avenue, just north of Union Square, then the center of New York’s theater district. In 1888, the "blue and the gray", Union and Confederate veterans, met for a reunion on the Gettysburg battlefield: the “battlefield” of the New York cyclorama. [9]

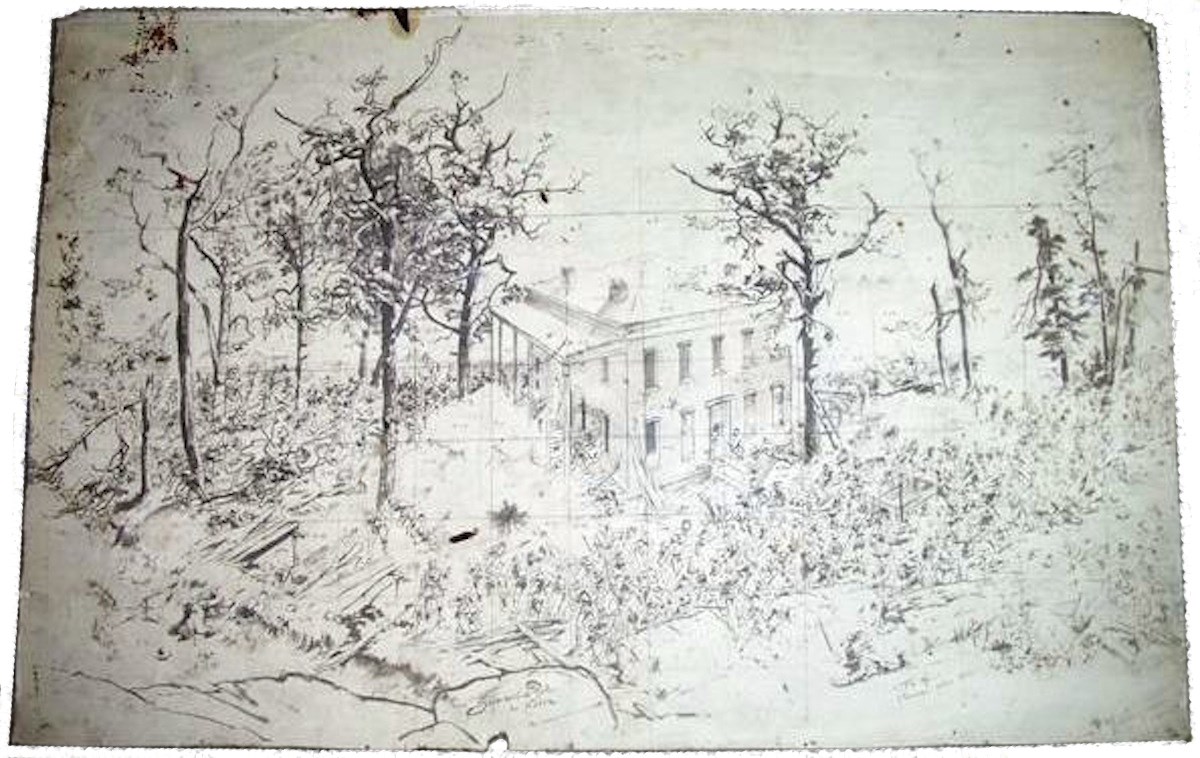

The Battle of Atlanta panorama depicts another Civil War battle-a Union victory-that culminated in the afternoon of July 22, 1864. This was a critical victory, contributing to the re-election of Abraham Lincoln and Sherman's "March to the Sea." The American Panorama Company, incorporated by Chicago investors in early 1884, hired William Wehner (1847-1928), a German-born Chicago businessman as manager, and built a studio in Milwaukee in which to paint panoramas. German and Austrian artists were recruited in Europe; some had previous experience in painting panoramas. The Battle of Atlanta followed the cycloramas Battles of Chattanooga, Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain. Two copies of Atlanta were produced: beginning in 1886, one was shown in Minneapolis, Indianapolis, and Chattanooga. It is this painting that has been in Atlanta since 1892. The second painting was shown in Detroit beginning in 1887, and then in Baltimore. The lead painter, Friedrich Wilhelm Heine, and landscape painter August Lohr visited the battlefield in October 1885 to do research: producing sketches and color studies, and interviewing Confederate and Union veterans. Theodore R. Davis, wartime illustrator for Harper's Weekly, who had been at the battle and sketched the action, was also in Atlanta with Heine and Lohr.

Although the first painting was well attended when it opened in June 1886 in Minneapolis, it was bankrupt in 1890 after a run of twenty-seven months in Indianapolis; the second painting was put into storage and the cyclorama building was demolished in 1891.

The cyclorama fad was fading. A 1903 insurance guide advised agents to decline to insure panorama paintings or their rotundas: the "buildings are unsuited for any other use and are undesirable."[10] By this time, many had been converted to other uses-theaters, roller skating rinks, automobile garages-but many were demolished as their city locations made their sites more valuable as real estate. Cycloramas continued to be a feature of World's Fairs and similar exhibitions: Emmett W. McConnell (1868-1965), known as "The Panorama King," bought many cycloramas and displayed them at these venues, thus keeping them in the public eye longer than they would have been otherwise.

The Philippoteaux Gettysburg that had been shown in Boston was reported in 1901 to be stored in a rubbish-filled vacant lot in a wooden box 3 feet high, 2 1/2 feet wide, and 50 feet long. It had been there for years in the sun, rain, and snow; some boards had been pried away, allowing further damage to the painting. [11]

As the cyclorama fad faded, the movement to commemorate Civil War battles and preserve battlefields that had begun in the late 1800s increased. Many battlefields had remained relatively untouched, and veterans could remember details of the battles; reconciliation between Union and Confederate veterans unified these men to push for federal support for battlefield preservation. In 1864 the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association was formed to preserve portions of the battlefield as a memorial to the Union Army. By 1893 over 850 monuments had been placed on the battlefield. The organization’s land holdings were transferred to the Federal government in 1895, when Gettysburg was designated a National Military Park, along with four battlefields: Chickamauga, Antietam, Shiloh, and Vicksburg. Administration of the park was transferred to the National Park Service in 1933.

The opportunity to preserve the battlefield was lost in Atlanta, which was omitted from the government-established military parks. About 40% of the city had been demolished and burned in 1864, and much of the battlefield terrain was eradicated as rebuilding and urban development took place. [12] A proposal in 1900 to form an Atlanta National Military Park was never adopted by Congress: The United States War Department felt it had already set aside enough land for battlefield parks.

Atlanta

Unlike Gettysburg, the Battle of Atlanta painting was not rolled up and forgotten: Emmett W. McConnell had sold Southerner Paul Atkinson a cyclorama in 1890. Atkinson’s father and four oldest brothers had all served in the Confederate army; Atkinson himself had worked in real estate, manufacturing, and show business, and thought that Civil War cycloramas could be profitable in the South. He bought the Indianapolis Battle of Atlanta for $2,500, and, with other investors, put up cyclorama buildings in Chattanooga, Nashville, and Atlanta, planning to rotate two paintings between those cities. This was risky: would white Southerners pay to see Yankee victories as illustrated in cycloramas?

So, some changes were made: for example, when Atlanta was shown in Chattanooga, a group of Confederate prisoners being rushed through Union lines had had their uniforms repainted in blue, thus becoming a group of fleeing Yankee soldiers. The painting came to Atlanta in 1892, billed as "The only Confederate victory ever painted," with Atkinson lecturing on the viewing platform, claiming that the loss of the battle by the Confederacy was only due to the overwhelming number of Yankee soldiers fighting in the battle. Some of the tales told about scenes in the painting, like that of two brothers fighting on opposite sides, were almost certainly invented by Atkinson.

But in 1892, the business venture failed: there were not enough paying customers to support the cost of leasing the land, erecting the buildings, moving the paintings. In 1893 an Atlanta lumber merchant and Union Army veteran, George V. Gress, bought the painting at auction and moved the building and painting to Grant Park, site of the city's zoo, but this venture also failed, and the painting was donated to the city of Atlanta in 1898.

Gettysburg

In 1910, an attempt was made to bring a Battle of Gettysburg cyclorama to Gettysburg when a group of Washington capitalists took a ninety-day option on a property on which a concrete and steel building was to be constructed: ”special effort will be made to secure tourist trade" to the city and the cyclorama. Contracts with railroads were planned to sell tickets to view the painting.[13] The plan fell through and the cyclorama, which had not been displayed for 15 years, was sold to Chicago junk dealers for one dollar. This painting was probably a Chicago Gettysburg that had been owned by Howard H. Gross and Isaac Newton Reed, panorama promoters who owned the Englewood, Illinois studio. By 1912, a plan to bring a cyclorama to Gettysburg was again in the works, and the building finally opened in 1913 on the fiftieth anniversary of the battle. By this time, the Boston version of the Gettysburg cyclorama was owned by Albert J. Hahne, who had shown the painting in his Newark, N.J. department store, hanging in pieces from the balcony of the interior court, in an armory in New York City, and in Washington's Pension Building: in none of these venues could the painting be displayed in its correct circular form. At Hahne's death in 1936, the painting and building were placed on sale by the executor of his estate and finally, in 1942, the National Park Service acquired the building and cyclorama painting for "one dollar and other valuable considerations."[14] The building in which the painting was housed was unheated and had no humidity controls, and no viewing platform. Richard Panzironi, a New York artist, "stabilized" the painting in 1948, cleaning it, sewing sections of canvas in torn areas and painting them. Supports were added to the back of the painting, and the bottom was allowed to hang free; this ultimately caused more damage. Both the painter and superintendent of the local National Park warned that the painting might someday be completely ruined if it were not placed in a heated building with humidity controls, one with a viewing platform to allow spectators to view the painting as intended. [15]

To coincide with the Civil War centennial, a new Cyclorama Center opened in Gettysburg in 1962-a Modernist building designed by architect Richard Neutra, placed as close as possible to the location depicted in the cyclorama. This was part of “Mission 66,” the National Park Service’s effort to upgrade visitors’ facilities by the fiftieth anniversary of that organization. The painting was once again conserved, but when installed in the new building, it was 356 feet in circumference and 26 feet high: a significant part of the sky, and a fourteen-foot-wide vertical section had been lost over the years.[16]

In 1970 the NPS estimated attendance at the battlefield at four million visitors; many main roads had been made one-way to facilitate traffic.[17] A 307-feet tall tower was opened in 1974, after much opposition; one writer called this “an insult to hallowed ground.”[18] A 1982 article in the Weekly Gettysburgian asked, “Will Fast Food Win The Battle Of Gettysburg?,” a reference to the fast food franchises near the visitors Center.[19]

In 1999, the National Park Service announced that the Neutra building would be demolished and the painting moved as part of an effort to restore the battlefield to its 1863 appearance. The cyclorama was removed for restoration and conservation in 2006, and 2009 the original visitor center and a parking lot next to it were torn down; despite opposition to the demolition of the Modernist Neutra building, it was ultimately torn down. Again, the painting was restored; in some cases, previous restoration had caused damage that had to be reversed: the painting had been badly glued to a new backing and had suffered water damage. Cleaning of the canvas was badly needed, fifteen feet of sky had been damaged and removed over the years, and there were some gaps in the painting where panels had been removed; some overpainting was flaking away. And the hyperbolic curve, required for the correct illusion, had to be added back. Restorers David Olin, Perry Huston, and experienced panorama restoration experts from Europe did the huge amount of work required. The painting is now housed in a building that resembles the red exterior, cupola and stonework of the round barns in the region, but the shape is based on historic panorama rotundas. Viewers ride an escalator to the viewing platform, which is at the correct height for the proper illusion; the Americans with Disabilities Act requires that a lift be available, which has been made as unobtrusive as possible.

Atlanta

In 1921 the old wooden cyclorama building in Grant Park was finally replaced by a "fireproof" steel and brick building, which housed the cyclorama, a museum and, in 1927, the locomotive Texas of the “Great Locomotive Chase.” In 1934, funding from the Works Progress Administration allowed restoration of the cyclorama and the "diorama" at its base. To cover a missing section of canvas, more Confederate soldiers were painted in; trees were painted in to hide a tear in the canvas and cover a company of Union soldiers-these were only a few of the alterations. In 1939, when the city of Atlanta hosted the segregated premiere of the new movie Gone with the Wind, based on the book by Atlanta's Margaret Mitchell, the movie stars visited the cyclorama; a plaster figure of star Clark Gable as Rhett Butler was later added to those of dead Union soldiers in the faux terrain.

With the desegregation of Atlanta and public institutions in the 1950s and 60s, and the election of the city's first African-American mayor, there was concern that the needed repairs to the painting, by then a Confederate icon, would not be funded. But the mayor supported the repairs and, between 1979 and 1982, the painting was restored, backed with fiberglass and the diorama reworked. A revolving viewing platform, which rotated seated spectators as a recorded narrative (with sound effects) described the painting, replaced the static platform.[20] Problems remained: the painting was not properly tensioned and suffered from excessive moisture; missing its hyperbolic curve, it hung like a curtain, with wrinkles and drag marks visible on the canvas. The fiberglass lining appeared to have solved this problem as of 1982, but the wrinkles gradually reappeared over time due to lack of proper tensioning. And proper tensioning was not possible because the 1921 building was too small for the painting to achieve its full hyperbolic shape.

In 2012 it was decided that the Battle of Atlanta must be moved to a larger building, and two years later the Atlanta History Center signed a seventy-five-year lease with the City of Atlanta. The cyclorama (and the locomotive Texas) were moved to a newly constructed building—a huge job, as the 6-ton painting had to be scrolled around two huge tubes and transported to the new location. Restoration of the painting and reinterpretation of the cyclorama has begun, and it is scheduled to be on display again in November of 2018. As military historian Gordon Jones wrote, "The Battle of Atlanta is an outstanding case study in popular historical memory as it ebbs and flows over the years, continually rewriting the histories of victors and defeated alike, always revisionist, always dependent upon the present, never settled."[21]

The location of both the Gettysburg and Atlanta cycloramas has changed over time: but, after all, the paintings were meant to be shown in multiple cities. The buildings have changed: from castle-like structures, or fairly plain temporary buildings, to buildings that are thought to fit in better with their battlefield or downtown city locations. Tourists now arrive mostly by automobile, rather than by streetcar or railroad. But the cycloramas, almost miraculously, survive, despite an ever-changing "popular historical memory." We are lucky to have them.

Perhaps, however, we have come full circle? In 2007, the National Park Service, “after rethinking the way it presents the history of one of America’s the [sic] most pivotal battles,” opened a new Bunker Hill Museum, which includes a “cyclorama” by muralist John Coles. It is circular, but much, much smaller than the old cyclorama size, and is apparently not a recreation of the Battle of Bunker Hill shown in Boston in the late 1800s, as it includes images of black and Native American soldiers.[22]

Circular paintings of battles are still being painted in China, North Korea, Russia, and Turkey. Artist Yadegar Asisi is creating huge panoramas that are digitally printed, and shown in old gasholder buildings or temporary buildings, primarily in Germany.

Notes

- Richard Altick, The Shows of London (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 1978), 181.

- Altick, The Shows of London, 136.

- Stephan Oetterman, The Panorama, History of a Mass Medium, trans. Deborah Lucas Schneider (New York: Zone Books, 1997), 49-59

- Erkki Huhtamo, Illusions in Motion, (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013)

- Altick, The Shows of London, 505-506.

- Gordon L. Jones, “Yankees in Georgia? How The Battle of Atlanta Became a Confederate Icon” (paper presented at the International Panorama Council conference, Namur, Belgium, September 9-12, 2015.)

- “A Good Paying Investment.” Daily Saratogian (Saratoga, NY), November 15, 1887. http://fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html

- Engineering & Building Record and the Sanitary Engineer: Volume 16, November 19, 1878, 708. https://books.google.com/books?id=vHFJAQAAMAAJ

- “A Pleasant Reunion. Blue and Gray Meet Again at the Gettysburg Battlefield.” The New York Times, August 16, 1888.

- Francis Cruger Moore, Fire Insurance and how to Build. (New York: The Baker & Taylor Company, 1903), 457.

- “Fate of a $100,000 Painting. Philippoteaux’s Cyclorama of the Battle of Gettysburg Neglected in Boston.” New York Sun, March 10, 1901. http://fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html

- Daniel A. Pollock, “The Battle of Atlanta: History and Remembrance.” Southern Spaces, May 30, 2014. Httpt://southernspaces.org/2014/battle-atlanta-history-and-remembrance.

- “To Bring the Big Cyclorama to Gettysburg.” The Gettysburg Compiler, March 19, 1910. Boardman Collection/Atlanta History Center.

- “Cyclorama is Acquired by Park Service.” Star and Sentinel, April 4, 1942. Boardman Collection/Atlanta History Center.

- “Artist Repairs War Painting at Cyclorama.” Star and Sentinel, July 31, 1948. Boardman Collection/Atlanta History Center.

- The Gettysburg Cyclorama Building, Gettysburg Daily, September 10, 2010. https//www/gettysburgdaily/com/the-gettysburg-cyclorama-building/

- Fritz S. Updike, “Purely Personal Prejudices.” Rome, NY, Daily Sentinel, November 30, 1970.

- John Pinkerman, “Visit to Gettysburg worth longest detour.” Rome, NY, Daily Sentinel, February 6, 1975.

- “Will Fast Food Win the Battle of Gettysburg?” Weekly Gettysburgian, March 8, 1982. http://idnc.library.illinois.edu/cgi-bin/illinois?a=d&d=GTY19820308.2.36&srpos=1&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-fast+food+battle+of+gettysburg-------

- “Cyclorama,” New Georgia Encyclopedia_ Cyclorama, accessed May 20, 2005

- Gordon L. Jones, “Yankees in Georgia? How The Battle of Atlanta Became a Confederate Icon” (paper presented at the International Panorama Council conference, Namur, Belgium, September 9-12, 2015.)

- Michael Levenson, “At Bunker Hill, history receives a makeover,” The Boston Globe, June 13, 2007. http://archive.boston.com/news/local/articles/2007/06/13/at_bunker_hill_history_receives_a_makeover/

Bibliography

Altick, Richard. The Shows of London. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 1978.

Boardman, Sue and Kathryn Porch. The Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama, A History and Guide. Gettysburg, Pa: Thomas Publications, 2008.

Brenneman, Chris and Sue Boardman. The Gettysburg Cyclorama, The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas. El Dorado Hills, Ca: Savas Beatie LLC, 2015.

Holzer, Harold and Mark E. Neely, Jr. Mine Eyes Have Seen The Glory, The Civil War in Art. New York: Orion Books, 1993.

Huhtamo, Erkki. Illusions in Motion. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013.

Oeterrman, Stephan. The Panorama, History of a Mass Medium. Translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider. New York: Zone Books, 1997.

Olin, David J, “A Public-Private Partnership and International Collaboration Save an American Panorama Treasure,” in: The Panorama in the Old World and the New, edited by

Gabriele Koller (Amberg, Germany: Buro Wilhelm. Verlag Koch-Schmidt-Wilhelm GbR, 2010) 120-125.

Wilburn, Robert C, ”The Campaign to Preserve Gettysburg” in: The Panorama in the Old World and the New, edited by Gabriele Koller (Amberg, Germany: Buro Wilhelm. Verlag Koch-Schmidt-Wilhelm GbR, 2010) 126-128.

Symposium

You can read other articles from the proceedings of Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Or explore other content from the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT).