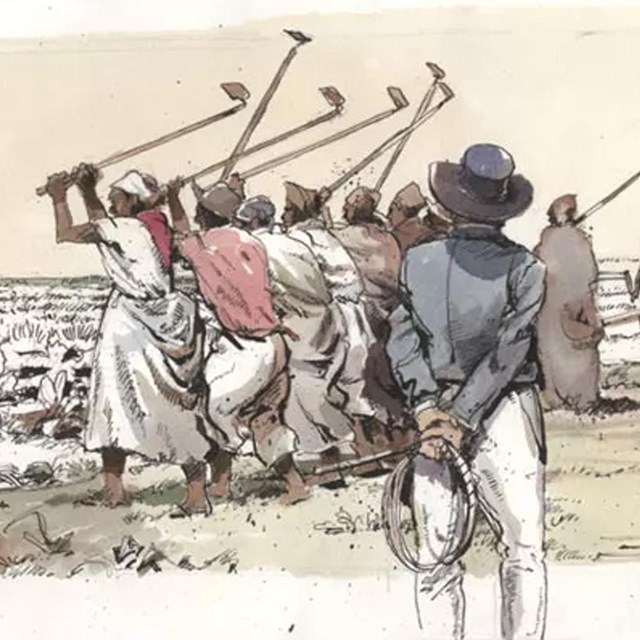

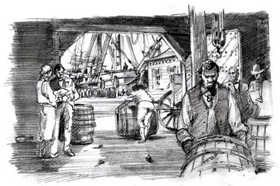

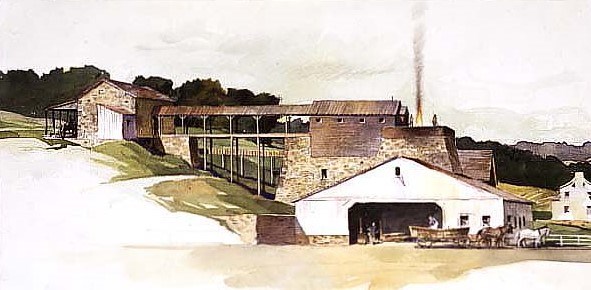

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center In the colonial period, Annapolis and Baltimore were major ports of entry for laborers called indentured servants from Europe. The Ridgelys purchased indentured contracts for at least 300 people between 1750 and 1800. Most of these servants had been convicted of crimes in England and Ireland. For many, their “crime” was being impoverished. Those in poverty were unwanted in England and therefore were convicted of minor crimes such as vagrancy. They traded prison time for hard forced labor and passage to the New World, where hopefully, when their contract was over, they could have a fresh start. Yet nothing could make up for the fact that these people were an ocean away from home, friends, and family. Convict servants were not willing laborers, and the working conditions at Northampton Furnace was grueling and dangerous. The indentured labor was critical to the ironmaking process. Tasks included extracting iron ore and coal, mining and burning limestone, felling and cutting acres of timber, making charcoal and hauling fuel, iron ore, and finished products to and from the site.

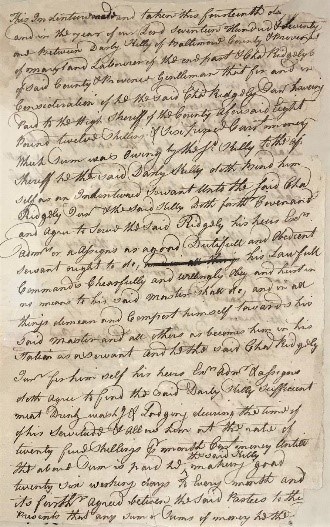

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center Farming was another facet of the work: indentured servants produced grains to feed workers and sell in the community. Many indentured servants were traded back and forth between forge, furnace, and plantation frequently and with ease. Some, however, were owned by the Northampton Company itself, so they most likely worked exclusively at the furnace. Indenture contracts were written between British agents or the servants themselves and Ridgely indenture purchasers. All Indentured servants were under forced labor conditions for a limited time. Non-convict indentured servants served terms of 4 to 6 years, while convicts had to serve at least 7 years. Those working within their contract found living conditions very similar to their enslaved counterparts, such as their less than substantial food and clothing provisions.

NPS Indentured servants at Hampton in the colonial period were all white, and therefore legal persons with legal rights. Many used the court system to argue that they were being held beyond their term. These legal disputes were complicated by the fact that the Ridgelys could change contract terms when servants sought their freedom, which many attempted. Learn More

|

Last updated: June 30, 2025