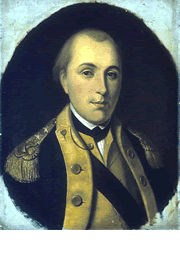

Artist: Charles Wilson Peale " This devil Cornwallis is much wiser than the other generals with whom I have dealt. He inspires me with a sincere fear, and his name has greatly troubled my sleep. This campaign is a good school for me. God grant that the public does not pay for my lessons." Marquis de Lafayette, July 9, 1781. Marquis de Lafayette On March 14, 1781, 23 year-old Major General Marquis de Lafayette arrived in Yorktown, Virginia, to start a campaign against the British that would culminate in their defeat six months later. Outnumbered and poorly supplied, Lafayette strove to improve the circumstances and numbers of his troops, often pledging his own funds to secure shoes and clothing for his soldiers. He also adopted a strategy similar to the one General George Washington had used thus far in the American Revolutionary War, that of limited engagement while preserving his forces. Lafayette’s first objective was to capture the American traitor, Benedict Arnold. Arnold, now a Brigadier General in the British army, had been sent to Virginia in December 1780 to raid military supply bases, gather support from loyalists, and weaken Virginia’s ability to aid Major General Nathanael Greene’s patriot forces in the Carolinas. Washington, intent on bringing Arnold in, sent Lafayette south with 1,200 troops and support from a small French fleet. On March 16, a naval battle between the French and British occurred near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, with the French fleet returning to Rhode Island and the British fleet linking up with Arnold and gaining control of the Chesapeake Bay. Lafayette, whose land forces were still at Annapolis, Maryland, could not combat Arnold, who was soon reinforced with 2,000 troops commanded by Major General William Phillips. Phillips, placed in overall command of British forces in Virginia, proceeded to conduct another raid, taking Petersburg on April 25. Phillips then moved towards Richmond, but by then Lafayette had his troops there and thwarted the British attempts to take Virginia’s capital. On May 13, Phillips died in Petersburg from fever, and Arnold was temporarily in command of the British army in Virginia. One week later, however, Major General Charles Lord Cornwallis arrived, bringing his army out of the Carolinas. With additional reinforcements from New York, Cornwallis was in command of over 7,000 troops. Arnold returned to New York. Lafayette, facing this new foe, wrote Washington on his ability to combat the British: “...A General defeat which with Such a proportion of Militia Must Be Expected would involve this State and our affairs into Ruin, Has Rendered me Extremely Cautious in My Movements. Indeed, I am more Embarassed to Move... Was I any ways equal to the Ennemy, I would Be extremely Happy in My present Command—But I am not Strong enough even to get Beaten.”

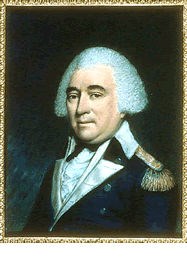

Artist: Thomas Gainesborough Lafayette vs. Cornwallis In late May 1781, Cornwallis moved to subdue Virginia. His forces raided as far west as Charlottesville and captured the main American supply depot at Point of Fork on the James River. Lafayette, reinforced with Pennsylvania Continental Line troops under Brigadier General “Mad” Anthony Wayne and Virginia militia under Major General Baron Friedrich Von Steuben, now had 4,000 troops. Though still outnumbered, Lafayette was able to shadow Cornwallis’ movements while working to equip his troops and protect military supplies. In mid-June Cornwallis halted his westward movement and turned towards the Virginia coast, reaching Williamsburg later in the month. Following a skirmish at Spencer’s Tavern west of Williamsburg on June 26, Cornwallis made plans to move his army across the James River at Jamestown and push on towards Portsmouth near the Hampton Roads Harbor with orders to establish a naval base. On July 6, Lafayette saw an opportunity to attack Cornwallis’ rear guard as he moved his army across the James River. It did not go as Lafayette had planned. The Battle of Green Spring While Cornwallis made preparations to move his army, he realized that as he ferried his troops across the river, those awaiting transport would be vulnerable to attack. Crossing only some of his cavalry and his baggage, Cornwallis gave the perception through information cleverly leaked to Lafayette, that only a small portion of his army was left near Jamestown. Lafayette, seizing the opportunity, sent Wayne and his corps of 800 men to reconnoiter the British position. Wayne moved cautiously, first stopping a couple of miles from Jamestown at Green Spring Plantation, where he tried to determine the true strength of Cornwallis’ forces. Lafayette joined Wayne at Green Spring, where they received further information that most of Cornwallis’ troops had crossed the river.

Independence NHP Moving south of Green Spring, Wayne encountered British pickets. Lafayette, taken by the tenacity of the British, moved along the river to get a better view of the enemy positions. There he discovered Wayne’s forces were about to encounter most of Cornwallis’ troops. By the time he returned to Wayne, Wayne’s troops were already engaged, too late to safely withdraw in the face of the enemy. Lafayette called up additional reinforcements who arrived as the British began to move on the flanks of Wayne’s battle line. Wayne, feeling a retreat at this critical moment could be disastrous, ordered an assault. The ensuing move against the British line temporarily halted the British advance, giving Wayne’s forces the opportunity to withdraw. The retreat was less than orderly, but the troops were successful in returning to Green Spring. Later that night Lafayette moved his forces further from the area, while Cornwallis remained in possession of the battlefield. Estimated battle losses for the patriots were 28 killed, 99 wounded and 12 missing. Total casualties for the British were around 75. In the aftermath of the largest infantry engagement to occur in Virginia during the American Revolutionary War, Lafayette issued general orders commending Wayne and his forces, noting: “The General is happy in acknowledging the spirit of the detachment commanded by General Wayne, in their engagement with the total of the British army, of which he happened to be an eye witness. He requests General Wayne, the officers and men under his command, to receive his best thanks.” Following the Battle In the aftermath of the Battle of Green Spring, Cornwallis moved on to Portsmouth. There the British army loaded onto transports. Lafayette wrote to Major General Nathanael Greene his perception of where Cornwallis’ forces were headed: “The British Army are in and about Portsmouth. An Embarkation is Certainly taking place and will Shortly Sail for Newyork.” In early August, Lafayette was surprised when the British fleet with Cornwallis’ army arrived in Yorktown and began fortifying the town and Gloucester Point on the opposite shore of the York River. Lafayette addressed the potential for trapping Cornwallis at Yorktown in a letter to the French minister to the United States, Chevalier de La Luzerne: “If the French army could all of a sudden arrive in Virginia and be supported by a squadron, we would do some very good things.” On August 21, Lafayette wrote Washington of the possibility of taking on Cornwallis: " In the present State of affairs, My dear General, I Hope You will come Yourself to Virginia, and that if the french Army Moves this way, I will Have at last the Satisfaction of Beholding You Myself at the Head of the Combined Armies... When a french fleet takes possession of the Bay and Rivers, and we form a land force Superior to His, that Army must Soon or late Be forced to Surrender as we may get what Reinforcements we please.” Unknown to Lafayette as he wrote his letter, Washington’s forces and a French army allied with him, had begun to move from New York to Yorktown, while a large French battle fleet was sailing for the Chesapeake Bay. Three weeks later, Washington reached Lafayette’s headquarters in Williamsburg and, at the end of September, marched on Yorktown with over 17,000 American and French soldiers. Lafayette commanded a division of American troops and was present at the siege and surrender of Cornwallis on October 19, 1781. Lafayette wrote his wife about the culmination of his Virginia Campaign: “The end of this campaign is truly brilliant for the allied troops. There was a rare coordination in our movements, and I would be finicky indeed if I were not pleased with the end of my campaign in Virginia. You must have been informed of all the toil the superiority and talents of Lord Cornwallis gave me and of the advantage that we then gained in recovering lost ground, until at length we had Lord Cornwallis in the position we needed in order to capture him. It was then that everyone pounced on him.” In November, Lafayette contacted the President of the Continental Congress for a leave of absence to return home, noting that “there is No Prospect of Active operations Before the time at which I May Be able to Return.” The following month, Lafayette returned to France and while he did make three trips back to the United States, the war had effectively ended with the Virginia Campaign at Yorktown. His military service to his adopted country had ended, while his lasting symbol of liberty had just begun. |

Last updated: February 26, 2015