DRAFT: Preliminary internal document in review/ Do not cite

This is an internal website intended to capture current approaches and knowledge base from the Natural Sounds & Night Skies Division in order to provide guidance to the field in an easy, user friendly format. It is still under development and this version was made available solely for this internal review. Following review, and prior to formal internal agency vetting, pages will be inactivated in order to incorporate input.

- Duration:

- 5 minutes, 5 seconds

An introduction to the protection of acoustic resources.

1 Introduction

This reference manual (RM-47) has been created to give park managers, planners, and employees the tools and information they need to implement Director's Order #47, Soundscape Preservation and Noise Management, NPS Management Policies, and other laws and regulations directing the NPS to protect the acoustic resources of national parks. It is designed to be an interactive guide to help park managers navigate the science, planning, and technical protocols used to manage acoustic environments in national parks in order to preserve the acoustic environment unique to every national park. Links to supplementary information are provided throughout the document.

1.1 Acoustic Resources and the NPS Mission

The mission of the National Park Service is to preserve the precious resources in our care and "to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

Like other natural resources and values managed by NPS, the acoustic resources are an important biological indicator, vital for healthy functioning ecosystems, and provide an essential part of the national park experience for most visitors. For definitions of terms relating to acoustic resources, see Appendix A. Glossary. For a list of authorities relating to acoustic resources, see Appendix B. Authorities.

The tranquility of historic settings and solemnity of memorials and battlefields, the sounds of thundering waterfalls, elk bugling, and winds whipping through quiet canyons are inextricable parts of the park experience. Natural and cultural sounds awaken the sense of awe that connects us to the splendor of national parks and have a powerful effect on our emotions, attitudes, and memories. Soundscapes are also essential components of wilderness character, enabling visitors to experience solitude, and "the earth and its community of life... untrammeled by man" (Wilderness Act of 1964).

1.2 NPS Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division

While RM-47 lays out the basic principles of acoustic resource management, the NPS' Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division (NSNSD) exists to provide support, coordination, and technical assistance to parks seeking to address soundscape management issues. Located in Fort Collins, Colorado, the NSNSD is part of the NPS Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Directorate. The Soundscape Program Center (later known as Natural Sounds Program), a precursor to NSNSD, was established in 2000. Today, NSNSD is the central policy and program office for management of acoustic resources in parks. NSNSD is responsible for providing assistance, coordination, guidance, and a consistent approach to addressing acoustic resource protection with respect to natural and cultural resources and visitor use. The program also provides technical assistance to parks in the form of acoustical monitoring, data collection and analysis, and in developing acoustical baselines for planning and reporting purposes. Park managers and employees should contact the NSNSD for advice as they embark upon activities related to acoustic resource management.1.3 Definitions

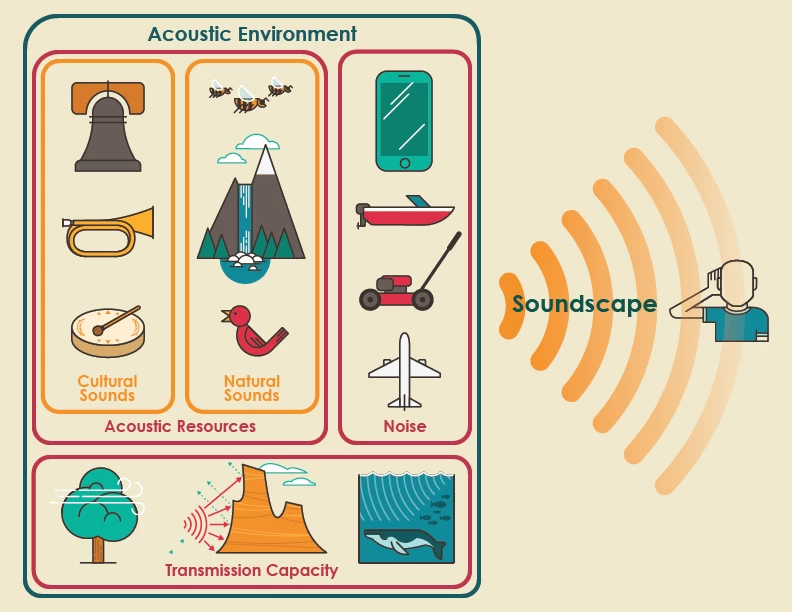

In recent years, understanding of the importance of the acoustic environment and its role in the protection of natural and cultural resources and visitor experience has evolved. As a result, the terminology used has evolved as well. Since NPS protects and enhances both park resources and visitor enjoyment, it is necessary to distinguish between the physical sound sources and the human perceptions of those sounds. In doing so, the NPS has adopted the following terminology that is consistent with ISO standard 12913-1. In this framework, all references to natural acoustic resources use the term "acoustic environment" and all references to the human perception of the acoustic environment use the term "soundscape" (see definitions below).

- Acoustic resources are the individual types of sounds that occur in national parks and include the sounds of nature (e.g. wind, water, wildlife, weather) and those sounds associated with cultural aspects of parks (e.g. battle reenactments, tribal ceremonies, quiet).

-

Acoustic environment is collectively, the combination of all sounds within a given area as modified by the environment. The acoustic environment results from the characteristics of numerous contributing sound sources and the ability of those sounds to propagate and attenuate. For example, in a forest acoustic environment, you might hear elk and wind rustling leaves whereas in a marine environment you would not. Note: This term is consistent with the definition of soundscape in Management Policies 2006 section 4.9 which describes "park natural soundscape resources" as encompassing all the natural sounds that occur in parks.

- Noise is extraneous, unwanted, or unpleasant sound. Sound is described as noise when it is unwanted, either because of its effects on humans and wildlife, or its interference with the perception or detection of other sounds. Appropriate sounds (such as human voices or transportation) can also become noise if they are excessively loud.

- Soundscape is the human perception of the acoustic environment. The soundscape, defined from an ecological perspective as the physical, biological, and anthropogenic sounds that make up a landscape, is thought to represent a ‘footprint of an ecosystem’, reflecting the dynamics of community structure and function (Schafer 1977; Pijanowski et al. 2011a; Pijanowski et al. 2011b). Soundscapes can reveal important information about underlying spatial and temporal distributions of vocal species in ecosystems, including changes in diversity, abundance, and behavior (Haselmayer and Quinn 2000; Celis-Murillo et al. 2009; Farina et al. 2011a).

Making the distinction between these terms allows managers to identify objectives, establish priorities, and implement targeted strategies for managing noise to protect park resources. Additional definitions are provided in Appendix A: Glossary.

Michael Warner, NPS

1.4 Importance of the Acoustic Environment

The acoustic environment is a natural system that includes all of the acoustic energy within a given area and an important component of a healthy and vibrant ecosystem. A fundamental concept of ecosystem management is the protection of physical systems such as the acoustic environment. These systems have inherent value that go beyond their importance for humans and wildlife. Consider the value that the acoustic environment adds to overall ecosystem health when assessing potential changes in acoustic conditions.

Wildlife

The acoustic environment plays an important role in ecological systems. The ability to both hear and be heard is fundamental for most wildlife. Animals listen to the acoustic environment to detect and decipher signals from conspecifics, predators, and prey. The acoustic environment results from the characteristics of numerous contributing sound sources and the ability of sound to propagate from one location to another. Sound is a fundamental component of a species habitat. Understanding the condition of the acoustic environment is important for evaluating animal communications systems as well as the impacts of noise.

Some groups of animals (especially in social species) benefit by producing alarm calls to warn of approaching predators and contact calls to maintain group cohesion. A reduction in communication distance created by noise might decrease the effectiveness of these social networks. Furthermore, many animals are known to eavesdrop on vocalizations from different species. For example, gray squirrels listen in on the communication calls of blue jays to assess site-specific risks of cache pilfering (Schmidt and Ostfeld 2008), and nocturnally migrating songbirds and newts use the richness and complexity of biological sounds produced in local environments to make habitat decisions. Animals also use accidental sounds produced by potential prey to locate their next meal; other animals use sound to avoid predation. At least one study, in which African reed frogs were shown to flee from the sound of approaching wildfires (Grafe et al. 2002), indicates that animals can use sound to avoid natural physical threats. It is likely that other ecological sounds are similarly important to animals.

These and other studies show that the animal communication and the interaction between wildlife and the acoustic environment is not a collection of private conversations between signaler and receiver but an interconnected landscape of information networks based on intentional and accidental sounds. Consider the importance of the acoustic environment when developing park planning documents, both in terms of the intrinsic value of natural sounds and their importance to the protection of wildlife species and ecological integrity. Learn more about the effects of noise on wildlife in this literature review, this literature synthesis, and the Supporting Literature page.

Cultural Resources

Cultural sounds often reflect a park's relevance, and help preserve the setting in which significant cultural events occurred. From culturally significant music, to sounds associated with notable events and historic reenactments, relevant cultural sounds are a protected resource in national parks. Examples of meaningful cultural sounds include jazz music in New Orleans, fog horn blasts at Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and Civil War reenactments at Gettysburg National Military Park.

Cultural sounds help reinforce a sense of pride in place, a connection to heritage and the awareness that humans, too, are integral to the soundscape at many national parks. Many anthropogenic sounds have embedded themselves in the American psyche and echo significant moments in the country's development. The whistle of a train, the heavy rattle of a slave's chains and the crack of musket fire are all imbued with meaning about the American experience. Cultural sounds are potent reminders of the role that soundscapes play in traditional practices, historical events, and ethnographic landscapes. Because of the impact that site-specific sounds can have on a visitors' experience, it is recommended that cultural sounds associated with the purpose and significance of the park be considered when developing park planning documents.

Visitor Experience

The visitor who experiences thundering waterfalls, male bighorn sheep butting heads, or a chorus of bird songs in the evening often cherishes these memories for a lifetime. As was reported to the U.S. Congress in the Report on the Effects of Aircraft Overflights on the National Park System (NPS, 1995), a system-wide survey of park visitors revealed that nearly as many visitors come to national parks to enjoy natural sounds (91 percent) as come to view the scenery (93 percent). Noise can also distract visitors from the resources and purposes of cultural areas--the tranquility of historic settings and the solemnity of memorials, battlefields, prehistoric ruins, and sacred sites. For many visitors the ability to hear clearly the delicate and quieter intermittent sounds of nature, the ability to experience interludes of extreme quiet for their own sake, and the opportunity to do so for extended periods of time are important reasons for visiting national parks. For example, birding is a popular activity in national parks, and most birders identify a bird by hearing its call before the bird is ever seen.

Human Health

Visitors can be positively or negatively affected by the quality of the acoustic environment. In relation to health and wellness, exposure to loud continuous noises is known to cause hearing impairment, sleep disturbance, cognitive interruption, hypertension, and other health detriments. Alternatively, hearing natural sounds is beneficial to human health and wellness by improving mood, cognitive performance, sleep quality, and other benefits.

Wilderness Character

Many parks contain areas that are designated, proposed, or managed as wilderness. NPS Management Policy 6.3.7 states that "wilderness is a composite resource with interrelated parts," and the acoustic environment is part of this composite resource. Preserving the acoustic environment and natural sounds of such areas are critical to effective wilderness stewardship. The absence of noise is crucial to the fundamental components of wilderness character: solitude, naturalness, untrammeled, and undeveloped. Noise, often from distant roads, park operations, park maintenance activities, or aircraft overflights, is one of the most common and pervasive human influences on the primeval character of wilderness. Natural sounds are one of the many components of wilderness, and remoteness from sights and sounds of people has been identified as an indicator for the wilderness quality “solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation” (Landres et al. 2008). Further, natural sounds are a key attribute for how visitors define wilderness character (Watson et al. 2015). Low frequency anthropogenic sounds such as those from roadways and machinery or loud, persistent noises such as overflights can travel for miles, immediately compromising a hiker's sense of solitude, naturalness, or undeveloped character.

RM-47 Home

Next Chapter 2: Data Collection

Appendix A: Glossary

Appendix B: Authorities

Last updated: June 18, 2024