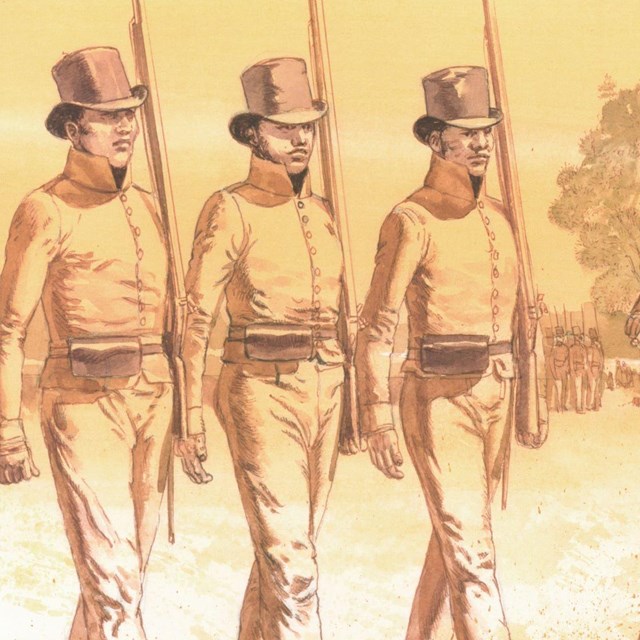

(c) Gerry Embleton Approximately 4000 enslaved men, women, and children, mostly from the Chesapeake, escaped from plantations and farms to the British during the War of 1812 to take their freedom. About 200 of these formerly enslaved men joined the British military as troops and were trained at Tangier Island where they were formed into the Colonial Corps of Marines, also known as Colonial Marines. The Colonial Marines, equipped with useful knowledge of the geography of the lands and waters around the Chesapeake, participated in several notable British raids on the Chesapeake including the British march of Washington D.C., and the Battle of North Point. At the end of the war, Great Britain agreed to resettle the Colonial Marines, and their families, in Nova Scotia and Trinidad. Between 1815 and 1821, nearly 700 formerly enslaved African Americans were resettled in six Company Villages in Trinidad at the instruction of Lord Bathurst, the British Secretary for War and the Colonies. Land in the Naparima district in the south of Trinidad was distributed to the former soldiers and their families. Although slavery was still legal in Trinidad, the Merikins were under the protection of British Superintendent Robert Mitchell.

National Archives of Trinidad and Tobago The conditions of freedom and resettlement in Trinidad were not all that these formerly enslaved families imagined. In addition to a lack of clothing and supplies, the gender imbalance of the community, and disease in the Company Villages, these families faced tension with the local population of free people of color who opposed the idea of self-emancipated, African descended settlers with military training living in proximity to enslaved people on properties in proximity to the Company Villages. Moreover, some of the villages were located on lands with poor soil, and like the African American settlers in Nova Scotia, those in Trinidad were not granted ownership of the lands on which they lived. This would change, however, in 1847 under the direction of Governor George Harris of Trinidad. Despite these challenges, the African American settlers developed a distinct community. As farmers they provided for themselves by growing corn, pumpkin, plantain, and rice. Whatever was left over as sold at markets. Some would work on nearby sugar estates, while others found work as blacksmiths, carpenters, and other trades. Within a decade of their arrival, the settlers even petitioned to Superintendent Mitchell for resources to establish their own schools and churches, laying the foundation for what would become the Spiritual Baptist denomination in Trinidad. Many of the descendants of these settlers still live in Trinidad, some still in the original towns formed in 1815. The descendent community refers to themselves as "Merikins," a term derived from "American" that recognizes and honors both the community's historical and cultural connections to the United States and the legacy of their self-emancipating ancestors. Transcription: “It is with pleasure I find myself enabled to report the continued progressive improvements of each of the Settlements, and general good conduct of the settlers; the major part of them have since the month of June returned from the Estates where they had hired themselves during the dry season, and have cleared and planted their respective allotments; the shew of the crops of corn, potatoes, pumpkins, &c. Is most luxuriant promising an maple return for the labor expended; the several allotments are at the same time getting rapidly planted with plantains and I expect by the month of September the whole of the cleared land will be planted with them.”

To read more about African American settlers in Trinidad during the War of 1812 and the Merikin community, please visit this article and this Guide to The Merikin Collection of primary sources organized by the National Archives of Trinidad and Tobago. Learn More

|

Last updated: September 24, 2025