What is a ghost town?A ghost town is a once thriving town that has been completely abandoned. Many of the logging or mining communities in Michigan from the 1800s are ghost towns today. Ghost towns allow us to question - Who were these people? How did they live? What were their dreams and aspirations? What happened? Can we avoid their mistakes?

Boom & Bust of Lake Michigan's Lumbermill ShorelineWhat we know as Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore today was first settled by Native Americans, known as Anishinabek, who migrated into this area about 8,000 years ago. Living in small settlements around rivers and lakes. The Anishinabek lived on fishing, gathering wild berries, hunting/trapping, and gardening, which provided corn, potatoes, squash, and pumpkins. They thought it would stay this way for ever, but European settlement would change their world dramatically. The first Europeans entered the area in the mid-1600s through the mid-1800s to explore and trade. Opening the Erie Canal in 1825 resulted in a dramatic increase in the use of the Great Lakes for shipping to transport people and goods to the growing Midwestern part of the continent. Great Lakes ship traffic quickly changed from schooners (2-masted sail boats), to steamships thanks to the steam engine.

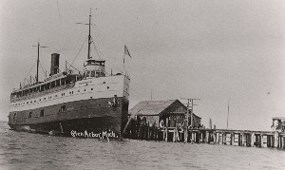

National Park Service The early steamships used wood for fuel. Making trips from Buffalo, NY to Chicago or Milwaukee required ships to stop for wood along the way. A dock was built on South Manitou Island in 1838, selling cord wood to the passing steamships. Increased need for cord wood led to a dock built on North Manitou Island. Small villages grew up around these docks, populated by the loggers and dock workers who supplied the firewood to the steamers. Because of the constant steamer traffic, these little ports became the transportation and commerce centers of the area. Depleting the forest of the Manitou Islands quickly, the search was on for a new supply of wood for fuel. Several cord wood businesses started on the mainland. Coal became the preferred fuel for the steamers, the cord wood business declined. Each logging village had a dock to load the cord wood or lumber on the steamships, one or more boarding houses where the workers would sleep and eat, a general store where they could buy whatever they needed, and a blacksmith shop to make and repair the metal tools and parts. There were also barns for the work animals (horses and oxen) used in the logging camps. After the lumberjacks and teamsters worked in a camp for a while they would bring their wives and children to the village. As the families moved in, small shacks, houses, and a school would be built. A logging village would have 100-500 residents, a couple of stores, post office, and school, which was often used as a community meeting place and church.

National Park Service By 1910 most of the trees were gone. When the trees were gone, the logging business was over. The sawmill would be torn down and the equipment put on a ship and moved to a new location. Then everyone would move out of town. Buildings would be torn down and the lumber would be used for other purposes, the village remaining only in the memories of the people who lived there. Few remnants remain - a foundation or a dock piling along the beach to mark the spot. Some communities made the transition to farming, fruit orchards and canning, or tourism to survive. Michigan's logging industry has taught us a lesson. Uninhibited exploitation of a natural resource is unsustainable business. Creating only short-term wealth and jobs. Today we know that businesses dependent on the use of natural resources must be managed in a sustainable manner to create long-term prosperity and minimize the impact on the environment. AralLocation:Aral was located on Lake Michigan where Otter Creek empties into the Lake just south of Esch Road, a few miles south of Empire, MI. Today this is one of the most popular swimming beaches in the Lakeshore, but in the 1880s, Aral was a booming lumber town! Earliest Settlers of AralWhen the United States acquired land, it first had to be surveyed before it was made available to individuals. In the summer of 1849, Orange Risdon was one of the surveyors assigned to the area around Grand Traverse Bay. In 1853 soon after he finished the survey, Risdon and his wife, Sally, bought 122 acres where Otter Creek emptied into Lake Michigan. Civil War Veterans move to AralThe US Civil War began in 1861, and to induce able-bodied men to join the Union forces, the US government offered $100 bounty to men who enlisted. By 1863 the bounty was increased to $300, and finally a draft was instituted. An interesting provision of the draft act allowed drafted men to avoid service by hiring a substitute or by paying $300.One of the men receiving draft notice was Robert F. Bancroft, who was married and 30 years old. He chose to hire a German immigrant to take his place as a soldier, and followed his replacement to the battlefield. Instead of carrying a gun, he brought his camera and became one of the first battlefield photographers. Following the war, the veterans returned home, and Robert Bancroft settled with his wife Julia and daughter Anna in Traverse City. He began buying land in Platte and Lake townships as investments and in late 1864, he bought the 122 acres from Orange and Sally Risdon. Bancroft cleared 20 acres and built a log cabin for his family to live in. Then he planted some black locust trees and an apple orchard around the cabin. Lumber speculators soon arrived looking for stands of white pine. Lumbering Arrives in AralMost of the forest in this area was hardwood, but there were some stands of white pine inland from Otter Lake. Lumber speculators were on their way north as the forests near Grand Haven and Muskegon were harvested. Dr. Arthur O'Leary, a distinctive looking man of Irish decent, recognized the financial potential of the lumber around Otter Creek. Buying up large tracts of forest, he made plans to build a sawmill despite having no experience in the lumber business. O'Leary found Charles T. Wright, who had a lumber operation with his brother in Racine, WI. Charles Wright would become the manager of the lumber operation at Otter Creek and a central figure in the first murder of Benzie County. The sawmill was built on the south side of Otter Creek not far from Lake Michigan. It was a 2-story wood building typical of sawmills of that time. The creek was dammed to create a mill pond right in front of the sawmill. The logs were floated down the creek to the mill pond and then lifted from the pond up an inclined ramp powered by the steam engine. The sawing was done on the second floor. A boarding house was built south of the mill, and horse barns were built north of the creek. Mill operation began in 1881 producing white pine lumber. The mill was idle during the winter, but the woods were alive with loggers working the logging camps. Wright employed about 150 workers throughout the winter and about 50 in the summer to run the sawmill and dock. Many of the other men went home to run their farms during the summer. Wright commuted between Wisconsin and Aral for several years, but by 1888 he built a house across from Robert Bancroft and he and his wife of four years moved in.Sometime before 1889 the mill burned down, but O'Leary paid to have a new, bigger mill built. In 1888, O'Leary sold the mill to Helene Davis of Brookline, MA, but Wright retained the lease on the mill. Charles Wright managed the lumber operation well, but he had a bad temper and a reputation for fighting. Business at the mill went on as usual until 1889, when a rivalry developed between the sawmills at Aral and Edgewater. The political details behind the situation are not known, but the taxes on Wright's sawmill operation increased to a rate Wright believed to be unreasonable, and in protest he did not pay his taxes that year. A writ of attachment was obtained by the sheriff of the county to apply to the mill yard's logs. This would have brought the operation to a halt and forced Wright to pay his taxes.

Benzie County Sheriff, A. B. Case, handed the writ of attachment to his deputy, Neil A. Marshall of Benzonia. Marshall was a big man standing about 6'6" tall and heavy set. On the morning of August 10, 1889, Wright heard that the deputy sheriff was on his way to Aral to implement the writ. Wright picked up his Marlin rifle and went with his crew to the rollway just above the bridge to start rolling logs into the creek which would carry them to the mill. About 10:00 AM, deputy Marshall arrived and ordered Wright to stop moving the logs. A confrontation occurred, but Wright's men continued working, and around noon Marshall went to the hotel for dinner. After dinner, Marshall was joined by Dr. Frank Thurber, the Lake Township Treasurer who was responsible for issuing the writ of attachment for the logs. They went to the log rollway and mill yard. From the company blacksmith shop, the blacksmith saw them approaching and told Wright who was there on an errand. Wright picked up his gun and went out to meet them. A struggle developed between Wright and Marshall. Wright released his grip on the rifle, took a few steps back, raised the gun and fired, killing Marshall with a single shot. Thurber then struggled with Wright for the rifle. After a short struggle, Wright released his grip on the rifle and pulled out a revolver from his pocket and shot Thurber in the head. He then shot Thurber again in the chest killing him. EdgewaterLocation:The Edgewater village and sawmill were located on the West end of Platte Lake, which is not part of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, but the railroad grade from the sawmill to the dock on Lake Michigan runs along the edge of the Platte River Campground. In fact, the hiking trail from the campground to Lake Michigan follows the old railroad grade. Take a walk to the back of any of the campground loops and take the trail to Lake Michigan and look for pilings that remain of the Edgewater Dock. First SettlementWhen the United States acquired land, it first had to be surveyed before it was made available to individuals. In the summer of 1849, Orange Risdon was one of the surveyors assigned to the area around Grand Traverse Bay. In 1853 soon after he finished the survey, Risdon and his wife, Sally, bought 122 acres where Otter Creek emptied into Lake Michigan. Edgewater Sawmill The Edgewater sawmill was owned by a man named Little and his two sons. It was probably first built around 1880 and shut down around 1900. One son was the Head Sawyer for the mill, and one day he was putting a belt on one of the pulleys in the sawmill and his thumb got caught between the belt and pulley. He grabbed onto something to keep himself from being pulled into the machine and held on for dear life! His thumb was pulled right off his hand, but it likely saved his life. The other son ran the boarding house in town. Edgewater locomotiveThe locomotive was built by Robert Blacklock, a master mechanic at the iron foundry in Elberta, MI where it was used to haul hardwood to the furnaces at the foundry for conversion into charcoal. After the foundry was closed, the locomotive was taken to Edgewater to haul lumber from the mill to the dock. The locomotive consisted of an upright steam engine mounted in a boxcar with chain drive. Rumor has it that one day the locomotive took off on its own and rolled down the slope to the end of the dock and right into the water where it disappeared and probably rests to this day. Good HarborLocation:Good Harbor is located in the northern part of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore at the Lake Michigan end of County Road 651. The only evidence of the village is a few dock pilings near the Lake Michigan shore. Lumbering in Good Harbor The village of Good Harbor was started in the mid-1870s when a man named Vine built a small sawmill and dock. He got white ash logs from the surrounding area, which he cut into 4" lumber for wagon tongues and shipped it by boat to Milwaukee and Chicago. His mill was in operation for a couple of years before he sold out to Henry Schomberg of Milwaukee and Jake Schwartz of Leland, who began making barrel staves, headings and hoops to supply packaging for shipping pork, fish, apples and other products around the Great Lakes. More than a Sawmill Upon purchasing, Richard & Otto expanded the Schomberg Hardwood Lumber Company of Good Harbor. Richard managed the operation in Good Harbor and Otto stayed in Milwaukee handling the sale of their products and bought supplies for mill and company store. The dock was expanded to 500 feet, so up to four schooners could be loaded at a time. They shipped potatoes and other agricultural products from the area as well as lumber and forest products. North Unity (Shalda Corners)Location:North Unity is near where Shalda Creek empties into Lake Michigan. This is in the northern part of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. Turn onto CR 669 and drive to Lake Michigan Drive which is the dirt road just before you reach Lake Michigan. Turn left and drive 0.8 miles to Shalda Creek, where you will find a vault toilet near the roadside. Hike back along the creek to Lake Michigan. Or, you can park at the end of CR 669 by Lake Michigan and walk to the beach. Turn left and walk along the beach to Shalda Creek. This is the site of North Unity. There is no evidence of the village, but you can imagine it as you read the story of these hardy immigrants. Looking for Paradise North Unity began in 1855 by a group of Bohemians. They were from present-day Czech Republic and Germany, by way of Chicago. Francis (Frank) Kraitz, his wife Antonia, and their family arrived in Chicago from Pelhrimov, Bohemia in August, 1855. Shortly before their arrival, several German families and a few Czechs formed a society they called “Verein". Verein is the German word for club or association. Early Days of North Unity The immigrants built a wooden barracks partitioned into sections to provide temporary housing. The 150-foot by 20-foot barracks was to house the families through the winter. In spring they would select a farm site and build more permanent cabins. Some families built their own temporary shelters near the barracks. “Everybody had his own idea,” wrote Krubner. “Some houses were all covered with hemlock branches, leaving small openings for windows. They looked more like bear huts instead of homes for humans. Some places they built the log house so low it was difficult for tall man to stand up in one.” Expansion of North Unity As the weather warmed, individual families began to build their homes. They started gardens and grew wheat, potatoes, cabbage, beans, and corns. Cattle were brought from Chicago two years later to provide milk. Rebuilt from the Ashes In 1871, North Unity was destroyed by fire. Many families moved inland to what is now known as Shalda Corners (M-22 and County Road 669). They rebuilt their homes, post office, stores, school, and church. The original Shalda store at Shalda Corners was built on the Southeast corner by Joseph Shalda. After a few years, he built a larger store on the Southwest corner. It had a dance hall above the store and an icehouse for cooling dairy products and beer. Port Oneida VillageLocation: Follow M-22 north through Empire and Glen Arbor. About 3 miles past Glen Arbor, turn left on Port Oneida Road. Earliest SettlersCarsten Burfiend, Port Oneida’s first European resident, departed Hanover, Germany in 1846 and landed in Buffalo, NY before traveling by steamship to North Manitou Island. His wife, Elizabeth, remained in Buffalo. Upon reaching the island, he built a cabin and worked as a fisherman until 1852. He then purchased 275 acres of land on the west side of Pyramid Point and moved his wife and small children to what later became Port Oneida. Continuing to work as a fisherman, Burfiend also ferried early settlers between the islands and mainland on his fishing boat. The Burfiend family lived in a three-story log cabin. They faced extreme hardships in their early years, including the deaths of three sons from pneumonia or drowning. Expansion of Port OneidaThe arrival of Thomas Kelderhouse was an important event in Port Oneida’s development. He was responsible for developing most of the economic opportunities related to logging in the area. Thomas Kelderhouse was a successful businessman who owned ships that carried cargo on Lake Michigan. During one of his trips, Kelderhouse landed on South Manitou Island and reportedly admired the mainland, undoubtedly sensing the economic opportunities provided by the dense forests. Striking a deal with Carsten Burfiend, Kelderhouse agreed to build a dock if Burfiend provided the land, and by 1862 the dock was completed. The community of Port Oneida was named after the SS Oneida, one of the first steamships to stop at the dock. Changing LandscapeLumbering drastically altered the appearance of the landscape. By the 1890’s, most of the land had been logged off and most Great Lakes steamships were burning coal. Unable to compete with larger operations such as that of D.H. Day in Glen Haven, the dock and mill were sold. The loss of this industry and the death of Thomas Kelderhouse in 1884 led to the demise of the Kelderhouse fortune and the village of Port Oneida. As the logging operations closed down, the Port Oneida region transitioned to an agricultural area. The various the farms and families have a rich history in Port Oneida. North Manitou IslandThere are two different ghost towns located on North Manitou Island - North Manitou Island VillageLocation: CresentLocation: Cord Wood and Lumber IndustryThe island was first settled in the mid-1840s by Nicholas Pickard who started a cord wood business to supply the Great Lakes steamships with fuel. The dock was about 150 feet long and 60 feet wide. Eventually the ships turned to coal for fuel and the logging operations switched to lumber production.Several sawmills existed on the island, but the last one still remains. It was built in 1927 using traditional technology. The steam engine and equipment date to around 1875 and the method of construction and style of layout are typical of sawmills of that era. Guiding Light in the Manitou PassageThe Manitou Passage was one of the busiest and most dangerous shipping channels on the Great Lakes. This created a business opportunity as a fueling and transportation hub. To provide safe passage, a US Life-Saving Station (USLSS) was established in the village. Many of the remaining buildings near the beach were part of the USLSS. A lighthouse was also established on the southern tip of the island at Dimmick's Point in 1898. This lighthouse fell into disrepair and is no longer standing.Changing Tides to TourismAfter the logging era, the cleared land was used for agriculture. Several fields and crops and orchards were planted. The village became the center of the community and was later used as the lodge for the Manitou Island Association, which by 1942 owned 70% of the island. The Association used the island as a hunting and fishing resort. The cottages that remain were used as summer cottages and guest houses.Settlement of Cresent The village of Cresent was built in 1906 when Peter Swanson leased a portion of his beachfront property to the Smith and Hull Company, which also bought 4,000 acres of prime timber land on the island. Work on the dock began in 1907. The dock was about 600 feet long and was completed in the fall of 1908. A sawmill provided lumber to build the houses and decking for the dock. On to the NextThe mill closed down in 1915 when the timber was all cut and processed into lumber. Smith and Hull abandoned Crescent and dismantled the mill and shipped the equipment to their next logging job. The Manitou Limited locomotive was loaded on a ship and sent to Virginia for more logging duty. South Manitou IslandLocation:From the current dock for the passenger ferry, hike approximately half a mile north along the shore. Alternatively, hike along the trail that goes through the Bay Campground until you get to the Old Dock Road. Turn right to go out to the old dock. Early Fueling StationOriginally settled in the mid-1830s by William Burton, fuelling the Great Lakes steamships with cord wood. His dock was built in the middle of the crescent-shaped bay on the eastern side of the island, the only deep-water harbor between Chicago, IL and Buffalo, NY. In 1847, the village included Burton's Wharf, a house, blacksmith shop, grocery store, barn, and a wooden tamarack railroad track extending from the dock inland to haul wood for the steamers. Shifting the Community CenterThe South Manitou Island Lighthouse was placed at the southeastern shore. This made for easy launching of rescue boats as well as proximity to the most dangerous parts of the passage. After logging operations ended and Burton's Wharf fell into disrepair, the Life-Saving Station complex became an important community center. Burdick’s moved their general store from its original location near the old dock to a site near the Lifesaving station in 1923, and that marked the shift of the island community to the current village site located at the present dock where the passenger ferry arrives. Sustaining Life on the IslandIsland residents made up a close-knit community. Over time, members of several farming families served in the Lifesaving Service or as lighthouse keepers. As island families grew, these career opportunities allowed islanders to make a living without having to leave the island. The houses provided a place for families to live together, since the Lifesaving Station provided housing for single servicemen only. The island became home to several family farms. Island agriculture moved into a new phase in 1918 when South Manitou Island was chosen by Michigan Agricultural College (now Michigan State University) as a site for growing Rosen rye seed. Compared to wheat and barley, rye has been cultivated for a relatively short time. Its principal use is for making bread. Rye depends on light, sandy soils typical of northern Michigan. It is easily fertilized and cross-pollinates like corn. Developing and maintaining a pure strain of rye is one of the most difficult problems in growing rye seed, so South Manitou Island was ideal because of its isolation from stray rye pollen. Eventually as roads and transportation developed on the mainland and ship traffic on South Manitou Island ended, the economics of farming on the island made it too expensive, and the families began to leave. |

Last updated: September 22, 2024