|

You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025.

Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. For current information,

visit https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/news/index.htm.

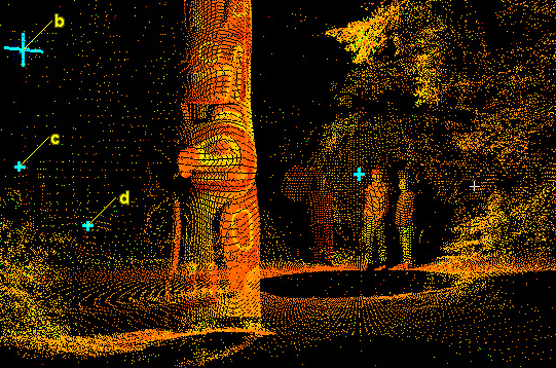

NPS Digital Rendering

Preservation of Sitka's Totem Poles Enters the Digital Age

By Michael Hess, Park Ranger

Following in the footsteps of the park’s first custodian, whose photographs documented the arrival of the park’s iconic totem poles, two specially trained architects digitally scanned many of the park’s totem poles this weekend for a special collection in the Library of Congress archives.

Collected by Alaska Territorial Governor John Brady to display at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis and 1905 Portland World’s Fair, the 14 totem poles from the original collection returned to Alaska and entered into the care of local photographer E.W. Merrill.

At first a volunteer and later personally selected as the park’s first custodian by Stephen Mather, first director of the National Park Service, Merrill oversaw their initial placement in Sitka – at Alaska’s first national park.

Since then, the efforts to preserve Sitka’s totem poles have become as much a part of the story of the objects as the cultural history told by the figures on the poles themselves. The digital preservation is only the latest chapter.

Park custodians have patched, painted, treated, and sealed the original poles, attached them to replaceable support poles raising their bases out of the ground, and commissioned the carving of new poles and also the recarving of the originals. For the poles that deteriorated too badly to stand safely, carvers turned to Merrill’s photographs for dimensions and appearance of the intricate figures.

The preservation performed by the architects from the National Park Service’s Heritage Documentation Program with their laser scanner serve the same purpose assigned to the photos by the commissioned artists, eliminating uncertain measurements for potential future carvings and facilitating precise cultural research.

The two-man team will transcribe the three-dimensional digital “point cloud” taken by the scanner into line drawings on archival paper vellum and submit them to the Library of Congress along with photographs and data points, capturing the poles’ existing conditions down to the millimeter.

The dimensions they record exactly capture the poles in a state that, according to heritage documentation standards, will be accessible for the next 500 years. Finally and permanently the team here solved the preservation aspect in a time-efficient and unobtrusive way.

However, drawings of the totem poles rendered even at the hand of a skilled architect using the latest technologies don’t fully capture the magnificence of these cultural objects. A large part of the experience of the totem poles at the park derives from walking among the Tlingit and Haida figures in the wooded setting, though the collection has a long history of equally impressive displays for large audiences outside the spruce and hemlock forest.

Even when raised in the grand, urban settings of the St. Louis and Portland, the totem poles retained the same allure for expo-goers and journalists that captivated famous naturalist John Muir, who called the poles he saw in 1879 “the most striking of objects.”

The current caretakers, too, want to carry the totem poles to a larger audience, and thanks to the digital preservation they’ll never need to move the objects. Heeding the NPS Director’s Call to Action #17 “Go Digital!," park management will create interactive tours from high-resolution photographs masked over the three-dimensional models of the totem, including a close look at each figure of each pole from the very top to the very bottom. Unlike the line drawings, however, the tour won’t meet any durability standards.

Just as the expositions were temporary exhibits, so are the virtual tours online. When the technologies used to the deliver the tours eventually obsolesce, the next generation of caretakers will once again continue the mission of predecessors Brady and Merrill – finding the best resources and venues to share the culture Southeast Alaska with the largest possible audience.

For Brady, showcasing the poles meant exposing 1.7 million visitors in two states to 14 totem poles collected from his territory. For Merrill, preservation meant photographing the totem poles, and establishing Alaska’s first national park to display them, which 200,000 people visit each year.

In the digital age, preservation means measuring these cultural objects with beams of light, and granting visitors worldwide access to the history of the poles, in high-resolution, away from the wind and rain – following in the footsteps of the caretakers who have worked to preserve and display these “these most striking of objects” for more than a hundred years.

|

Last updated: May 24, 2021