Unknown

P-25, a female, died of unknown causes in October 2012. | Photo: National Park Service

This is sometimes the reality of research. Results will come out inconclusive for a variety of reasons, such as finding a deceased lion after it began decomposing. In the case of P-25, the necropsy was inconclusive, but we did document rodenticide exposure, which could have played a role in her death. Speaking of which...

Rodenticide

P-22, the lion living in Griffith Park, was exposed to rodenticide, making him susceptible to mange. He was treated and recovered. | Photo: National Park Service

A little more to add to what’s already been said. It’s believed that P-3 and P-4, the two who died in the Simi Hills, had a tertiary exposure to the poison. That is to say, they were the third animals in the food chain for that meal. A woodrat, for example, could have eaten the poison, which was then eaten by a coyote, which was then eaten by the mountain lions. The poison just moved right on up the food chain.

This is not a pleasant way to die.

As for rodenticide in general, 11 of 12 mountain lions tested during our study have been exposed to anticoagulants. In fact, during nearly two decades of research in and around the Santa Monica Mountains, there’s been documented widespread exposure to anticoagulant rodenticide in local wildlife, sometimes leading to death. Of 140 bobcats, coyotes and mountain lions evaluated, 88 percent tested positive for one or more anticoagulant compounds.

Starvation/Abandonment

P-29 was abandoned by her mother and died in June 2013. | Photo: National Park Service

P-13 has given birth to at least three litters of kittens during the study. Her first litter in 2010 had three kittens. She abandoned one of the kittens, who died of starvation. The birth of her next litter was not documented, but she was later seen with two kittens. Her third litter was made up four kittens, of which two were found deceased. Abandonment isn’t unheard of, but there’s simply not enough research and data to begin to answering why and how often this occurs. Were the abandoned kittens sick? Could she not handle more than two and made a decision to leave behind the least fit? We just don’t know, but that’s one of the many reasons why we continue to study lions.

Vehicle Collision

P-A was found dead on Malibu Canyon Road on May 22, 2004. Lions not followed by our study are given a letter instead of a number. | Photo: National Park Service

Roads -- the second deadliest category in the study -- provide a window into habitat fragmentation and open space connectivity. Mountains lions have large ranges (they need between 75 to 200 square miles) and need to travel miles for food, marking and defending territory, breeding, and, for mothers of young kittens, avoiding adult males. The Santa Monicas are not pure open space, but rather a blend of that and private residences, all connected by streets -- some quiet, some quite busy -- and then flanked on all sides by nearly impenetrable forces: miles of ocean or miles of high speed freeway. Welcome to puma prison.

Our GPS data show many lions pushing up against the edges of freeways and then turning back. Those that do continue are rolling the dice. Twelve mountain lions, three from our study, have been struck and killed by vehicles in our study area since research began in 2002. (This post only examines the causes of death of animals we were tracking since, of course, we are much more likely to discover non-collared animals struck by vehicles than any other source of mortality.)

P-18 tried and failed on the 405 near the Getty Center. P-32

earlier this month met the same fate on Interstate 5 near Castaic Lake, this after safely crossing numerous busy arteries, including the 101 (he was the third to successfully cross it). P-9 demonstrated that it’s not always going to be a busy freeway that ends a life. He died on Malibu Canyon Road, which is considered a two-lane county highway.

Intraspecific Conflict

Female P-7 killed by father P-1 | Photo: National Park Service

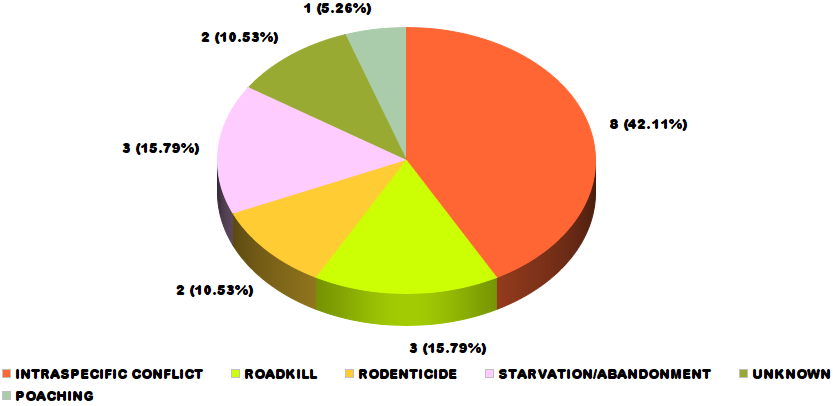

While crossing busy roadways is a major challenge in fragmented habitat, it’s not the only hurdle. As the numbers indicate, our study has so far found that mountain lions killing other mountain lions is the number one cause of death in the study.

It goes back to the need for a widespread range, especially for males, who stake out a large area for food and reproduction (females are generally welcome to stay within a male’s range). But a spatially constrained area where leaving is not an easy option, especially for dispersing young lions, creates intraspecific conflict.

That conflict on its own is not unusual in the world of mountain lions. In the Santa Monica Mountains, however, there’s an extra layer of uniqueness. The area is practically landlocked leading to conflict between close relatives. It’s speculated that the reduced ability of mountain lions, especially young males, to move out of the Santa Monicas, may increase the chances of aggressive encounters with adult male lions, often leading to these fatal events. The restriction on movement could also contribute to male lions killing females, even adult females that represent breeding opportunities. And all of this, say our researchers, is rare or nonexistent elsewhere where lions reside.

“[I]n the Santa Monica Mountains, we documented repeated cases of males killing their offspring, their brothers, and previous mates,”

wrote two of our wildlife biologists, Seth Riley and Jeff Sikich, with University of California colleagues in a September 2014 issue of the journal Current Biology. “Little has been reported about paternity or kin recognition in mountain lions, but clearly this is rarely a sound evolutionary strategy as the survivorship of offspring or siblings is traded against the probability of future reproduction.”

Interestingly enough, we’ve observed the opposite starting just hundreds of feet across the 101 Freeway in the Simi Hills, a northern gateway to the Santa Susana Mountains and Los Padres National Forest. Males P-12 and P-16 (both fathered by P-21) were born north of the 101 and successfully dispersed to establish their own home ranges. Meanwhile, if you’re a male mountain lion born in the Santa Monica Mountains, it’s unlikely you’re going to live beyond age two.

This all points to the need for a connection between the Santa Monicas and Simi Hills for those northward open spaces, which is important for the long term health of the species in the Los Angeles area. Our researchers have identified the area near Liberty Canyon Road in Agoura Hills as a critical location for a wildlife crossing of some sort.

* * * * *

There’s one more looming threat to mountain lions. It hasn’t occurred yet and, frankly, it’s one we hope to never observe. With the limited movement available, we’re seeing inbreeding. The dominant male lions are killing off male competition (usually sons or brothers) and reproducing with previous mates, their daughters, and even granddaughters. The genetic diversity of these local lions are some of the lowest ever observed. Physical effects have yet to be observed, but there is precedence for concern.

After more than 100 years in isolation, a population of lions, known as Florida panthers, began to see reproductive failure due to inbreeding. To help diversify the gene pool, lions from Texas were translocated.

We’re not to that point in the Santa Monicas, and translocating a lion from elsewhere could be one helpful tool in addressing the issue. But translocation into isolation is like a band-aid covering a cut that never stops bleeding. Connectivity appears to be the best long term solution.

And if connectivity happens, a blog post 20 years from now on the same topic could have a different ending. Death would still occur, but the countdown to genetically-caused local extinction would be gone. Researchers see that as a win.