Photo courtesy of Botanical Soc. of America

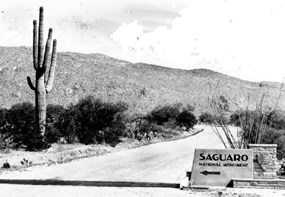

Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery On March 1, 1933, in the last days of his presidency, Herbert Hoover signed a Proclamation establishing Saguaro National Monument in the nearly empty desert, 15 miles east of the sleepy town of Tucson. Wrenched by the Great Depression and awaiting a new administration, few in Washington paid any attention to Hoover’s action. But it was a victory for both botanists and boosters in Arizona who’d worked for years to protect this grandest stand of saguaros. And it was a far-sighted accomplishment that would have incredible benefits for future generations of both Tucsonans and tourists.

NPS Photo It was in 1920 that members of the Natural History Society of the University of Arizona first expressed interest in preserving a stand of the West’s most iconic plant species. Already famous from countless silent movie westerns, the saguaro was high on everyone’s list as a symbol of the frontier. Still, desert land cost money, and the Society’s fund-raising efforts failed. But in 1928 University president Homer L. Shantz, in his role as a plant scientist, took up the cause. He envisioned a vast outdoor laboratory, ranging from the cactus-studded desert to the pine-wreathed mountains, free from human disturbance and studied by generations of student scientists.

Unfortunately, academics’ dreams and political realities seldom mesh. Although Shantz succeeded in purchasing some cactus acreage with University funds, it was clear that other means were necessary. First of all, the agency managing the mountains would have to agree to the grand design. After heated discussions the U.S. Forest Service reluctantly signed on, as long as they kept control and cattle grazing continued. The National Park Service, charged with preserving vistas of grand landscapes and objects of scientific interest, sent the Superintendent of Yellowstone, Roger Toll, on a winter trip to the desert. He liked the Cactus Forest but found the mountains uninteresting and the cost too high. The vision seemed to be fading.

NPS Photo But there were others in Tucson who saw the value and prestige of having a National Monument nearby. Frank Hitchcock, publisher of the local Citizen newspaper, active in the business community, and influential in Republican politics, knew the time was ripe for action in Washington. With help from both agencies he literally rushed to Washington to take advantage of a tradition started by Teddy Roosevelt – the proclamation of National Monuments at the end of a President’s term. With support from the Secretary of Agriculture and the promise of Forest Service management, Saguaro National Monument was born on the first of March, 1933.

But times change – sometimes quickly. Only two months later, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered that sixteen national monuments be transferred to the National Park Service and Saguaro began a long slow march to the treasured sanctuary it is today. Often the progress was painful: early rangers had to haul water from the center of town; “cactus rustling” was rampant; cattle continued to trample young cactuses for decades. Aging of the cactus forest and lack of regeneration led to a widespread belief that the saguaro was a dying breed, like the frontier life it symbolized. Efforts to close the Monument were suggested, but Washington took no action …

NPS Photo And there were successes. Homer Shantz continued his efforts on behalf of the Cactus Forest, leading to Civilian Conservation Corps construction of the famous Loop Drive (fully restored in the summer of 2006!) A Visitor Center opened in the 1950’s and important scientific research brought a fuller understanding of the saguaro life cycle by 1970. Most importantly, in 1961, at the urging of the people of Tucson and Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall, President Kennedy added 25 square miles of splendid cactus lands in the Tucson Mountains to the Monument. Finally, after setting aside vast areas as wilderness, Congress elevated Saguaro to National Park status in 1994. The simplest efforts long ago may have the profoundest effects upon us today... |

Last updated: May 5, 2025