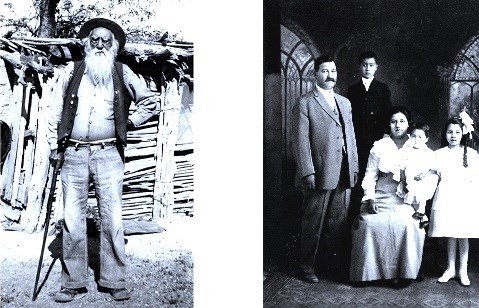

Right: Rafael Carrillo Family Photos courtesy of Arizona Historical Society Homesteaders of Saguaro National ParkThe surrender of Apache leader Geronimo marked the end of a troubled era in the Tucson Basin. The residents of the former Mexican village, protected by the U.S. Army's Fort Lowell, now began to move out to the valleys of Rincon and Tanque Verde Creeks—well-watered bookends to today's Saguaro National Park.

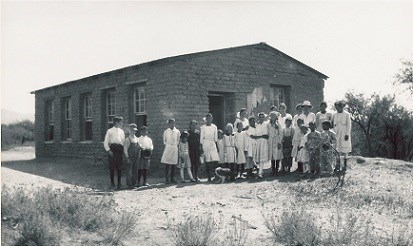

Photo courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society Along Rincon Creek, Fermin Cruz cultivated 20 acres for family use, selling the excess produce in town. The Cordova family grew "barley, chilis, squash, watermelons, corn, tomatoes, beans, and a little wheat." When the Knipe family consolidated these homesteads into large ranch, families stayed on as ranch hands and vaqueros, and a neighborhood school was built for the children.

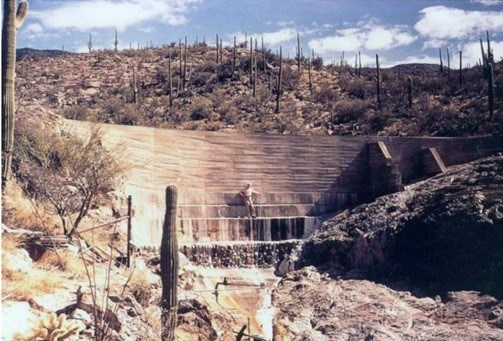

NPS Photo Garwood DamTucson residents Nelson and Josephine Garwood purchased 450 acres of vacant, unimproved land in what is now the northwest corner of the Rincon Mountain District. The parcel was bounded on three sides by Saguaro National Monument (made a National Park in 1994). The land was purchased in July of 1945 from two sisters who were the original homesteaders. Initially, access to the property was difficult, so Nelson constructed an access road to Speedway to the north. With mostly hand tools and dynamite, he constructed a passable road suitable for the trucks that would be required to haul building materials to the property. Dynamite drill holes are still visible along the very narrow portion of the road near the remnants of the residence. Nelson began construction of the first house, which was a small, one room affair with a half-bath in 1948. Shortly after completing the house, the Garwoods moved to Ohio to develop a family farm, then they returned to Tucson in 1950. At that time, they began construction of the main and larger house, which was above and behind the smaller original structure. A one-cylinder diesel generator provided electricity, heat was provided by a fireplace (some smaller rooms were heated with electric space heaters), and water was provided by the dam. There was no telephone or mail service. Work was begun on the dam in 1948, the same year as the original house. The Garwoods had noticed that water was always present in Wildhorse Canyon behind the house (although it did not run year-round), so Nelson decided to dam the drainage to provide domestic water. The dam was built in several stages. At first, the dam was little more than concrete and stone masonry. That was followed with steel and masonry walls filled with poured concrete, then followed with more poured concrete using plywood forms and metal (the texture of the plywood forms can be seen today—see photograph at left). Two 20,000-gallon stone masonry and concrete holding tanks were constructed for storage. Both were gravity fed and always provided an adequate water supply. An 8-inch pipe with filters at the ends was placed in the sandy area behind the dam, providing filtered water to the tanks. When completed, the dam held considerable water in the reservoir; however, sediment eventually would completely fill the reservoir to the top of the dam. The CCC and Saguaro National ParkThe Civilian Conservation Corps (originally designated the Emergency Conservation Work program) was a public work relief program that operated from 1933 to 1942 and was a part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal. The major objectives of the program were to give jobs to hundreds of thousands of discouraged and undernourished young men, ages 17 to 28, idle due to the Great Depression. The CCC would build up these young men physically and spiritually and start the nation on a sound conservation program to conserve and expand timber resources, increase recreational opportunities, and reduce the annual toll of forest fire, disease, pests, soil erosion and floods. The CCC provided the men (enrollees) with shelter, clothing, food and a wage of $30 a month, $25 of which had to be sent home to their families. Each enlistment period was for six months. To provide enrollees with necessary training for employment after discharge, a program of vocational and academic training was later added.

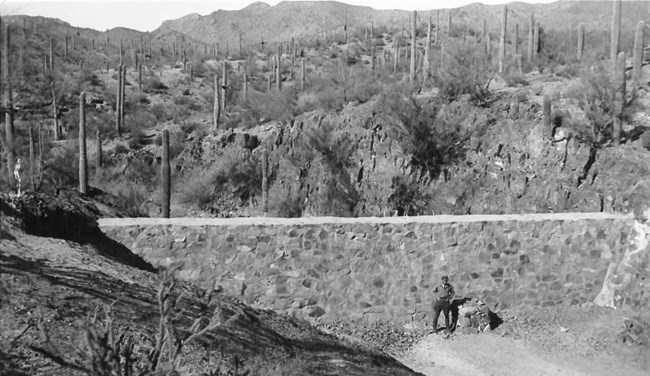

NPS Photo CCC DamsFrom 1933 to 1942, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) constructed water control dams in Tucson Mountain Park (TMP) and what is now the Tucson Mountain District of Saguaro National Park (TMD). The purpose of the dams was erosion control as well as to promote wildlife by establishing artificial watering sources. There are a total of 28 CCC dams at TMD and 3 at TMP. Rock and concrete dams were constructed of rock with concrete mortar. Many of the rock and concrete dams are battered, meaning they have a slight backward slant to them. These dams range in size from 12 to 30 feet long and from 3.5 feet to 18 feet high. All of these dams have silted up; only their downslope face is visible. Apparently all of these dams were constructed between 1934 and 1936. Gabion Style Dams are constructed of stacked rock, without mortar, held in place with 6” by 6” wire mesh anchored to wash bottom with 3” diameter metal posts. The dams may also be anchored at their ends by wire and metal posts. Five of these types of dams were constructed by the CCC. Some of the CCC documents refer to this type of dam as a “sausage” dam. The largest of the Gabion dams measure 60 feet long by three feet high. The two large earthen dams, referred to as Mine Dam 1 and 2, are constructed principally of earth and bolstered with a rock facing (or riprap) held in place with wire mesh along the upstream side. Both these dams have rock-lined spillways along their western end. The spillway allows water to build up behind the dam but keeps the water from overtopping the dam which would cause catastrophic erosion to their downstream side. Both of these dams are currently in a Pima County owned inholding within TMD. The largest of these dams measure approximately 116 feet long by 15 feet high.

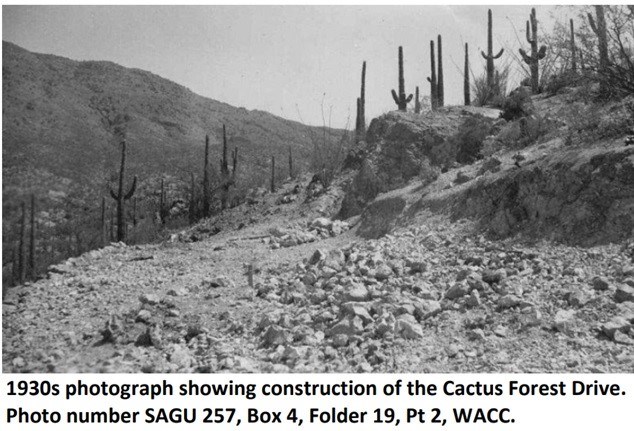

NPS Photo CCC and The Cactus Forest Loop DriveThe Cactus Forest Drive (originally designated Skyline Loop Road) was constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) between 1936 and 1939. The CCC Features associated with Cactus Forest Drive include the existing roadbed and alignment, multiple course-stone retaining walls, masonry culverts, and drainage-control features. Cactus Forest Drive was originally designed as a scenic loop road allowing visitors to experience Saguaro National Monument’s ecosystem at a leisurely pace. The original setting is intact and views in all directions remain relatively unchanged since the 1930s. The present landscape of Cactus Forest Drive still retains the visual character of the 1930s landscape design with overlooks and turnouts at various locations that provide opportunities for park visitors to view and experience the Sonoran Desert landscape in an unobstructed setting. The road continues to serve this purpose while maintaining the original road alignment and many original features that reflect the naturalistic design elements, philosophies, and architectural styles and building materials that reflect the National Park Service rustic design philosophy of the 1930s. Most of the work in Saguaro National Monument was undertaken by the CCC enrollees assigned to Camp Tanque Verde (SP-11-A). By 1936, the Skyline Loop Road, which became Cactus Forest Drive, was planned, staked, and the CCC men from Tanque Verde Camp began construction. In 1938, Camp Tanque Verde closed due to lack of water and the Skyline Loop Road was completed in 1939 by CCC crews from Randolph Park (SP-3-A). In 1951, the Cactus Forest Drive was regraded and paved; in 2006 the drive was rehabilitated, including repaving, minor widening to accommodate a bike lane, striping of road, and closure/rehab of some turnouts and improvement of others.

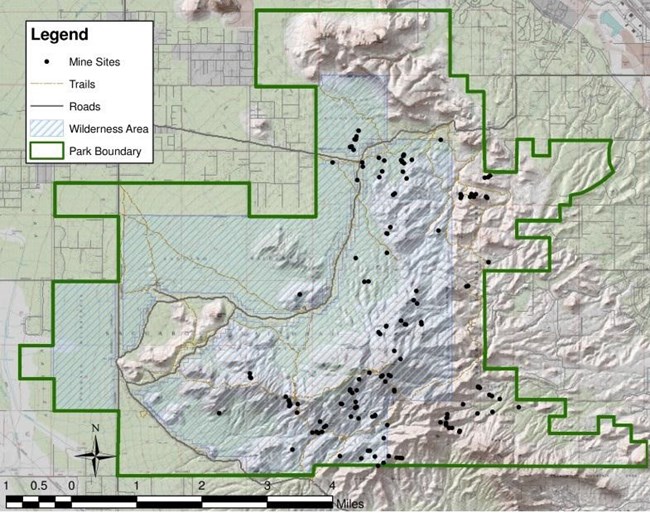

NPS Image The Amole Mining DistrictThe Amole District was an unorganized Pima County mining district, of which 137 mining sites are within the Tucson Mountain District of Saguaro National Park. Minerals sought in the district included copper, lead, silver, and molybdenum. The National Park Service has determined that the Gould, Copper King/Mile Wide, Jewel, Arizona Copper Mining Company, and Old Yuma mines are individually eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places at the local level of significance. The First MineThe Nequilla Mine (the first mine) was located on December 11, 1865 and is just southeast of the Saguaro National Park boundary. The claim was recorded by Jesus and Ramon Bustamente and Domingo Gallego on February 17, 1866. On the federal mineral survey map of this claim is a reference to the “Sierra de Amole Mining District.” The mineral surveyor located the mining claim in reference to “Soap Weed Peak,” a yucca plant commonly called by its Spanish name, “amole.” The mine was patented on September 28, 1872, making it the first patented mining claim in the Arizona Territory. The Nequilla Mine changed hands and was reworked a few times but closed for good in 1923 (Clemensen 1987:89-92). While registration of mining claims began to increase after 1872, they were mainly held for speculation. The district had spikes in activity usually coinciding with rising metal prices and national booms. There was no production phase, except minimally. The Arizona Bureau of Mines estimated a total production for the district of $44,000 worth of metal by 1936, an embarrassingly low product. During the 1880s, metal prices increased and the Southern Pacific Railroad came to Tucson. Hoping to find silver, claims were patented in the 1880s for the Silver Moon, the Lola Lopez, the New Strike, and the Buena Vista. The quest for silver was probably part of the post-Civil War interest in silver that dominated Arizona’s mining economy between 1865 and 1895. Not much silver has been produced in the Amole District. By the end of the nineteenth century, prospectors in the region began to take an interest in copper. A large number of claims were filed in the Amole District between 1897 and 1908. Most of the claims were filed by speculators. The Mile Wide MineThe major story of the Amole Mining District is the Mile Wide Mine located at the head of King Canyon and entirely within the park. It was started as the Copper King Mine in 1914 by Martin Waer, who sunk one shaft to 86' and found "very valuable" copper ores. In 1915, an investor named Reineger took an option witih Waer for $1,000 down and $74,000 due in four years. Reineger organized the Mile Wide Copper Company, named for the width of the 31 claims involved. Five million shares of stock were issued at $1 per share. After selling $40,000, Reineger started a new shaft uphill from the old one and hired 50 men. They found 4% copper ore at a depth of 95'. Reineger promoted more shares of stock through the Singer Co. of Pittsburgh. By 1917, the Arizona Star in Tucson reported discovery of a sensational chalcopyrite (copper pyrite) deposit of remarkable purity. Reineger built a haul road and used six trucks to haul ore to Tucson for rail shipment to SASCO (Southern Arizona Smelting Company). He built four houses, a workshop, mess hall / bunkhouse, rock crusher, hoist house and truck loading facilities. The shaft was sunk to over 400' with working levels at 100' intervals. By 1918, ore assays showed little value, and by 1919, when the $74,000 option was due, Reineger could not be found. In 1920, stockholders filed suit, and in 1921, Reineger's dealings became public. He had taken half the stock money for himself. In 1923, the court ordered Reineger to pay $134,000 plus $15,000 in attorneys fees. He was also ordered to endorse all stock and property to Union Copper Company of Pittsburgh, who auctioned all equipment for $3,000. The total production of the Mile Wide Mine was $10,000 in copper and $15,000 in silver. Several hundred thousand dollars changed hands and produced only $25,000. The Gould MineS.H. Gould established the Gould Copper Mining Company on 19 claims in 1906 during the period of the greatest rush to stake claims in the Tucson Mountains. By 1907, the shaft was 165' deep. He obtained a mortgage for funds, and by 1908, the reported depth was 375' with a vein 35' wide of chalcopyrite at teh 100' level, which widened to 60' at lower levels. The Arizona Star reported assays of 4% copper. There seemed to be some general belief at this time that a mine would find greater amounts of ore at greater depths, so it was speculated that they would be just as productive as the Silver Bell Mine when they reached a similar depth of 1200'. (The Silver Bell Mine was well known, located about 25 miles to the west.) The Gould Mine, however, had to shut down after 1908 and ceased all shipments except from surface stockpiles until 1911. By 1915, Gould was in bankruptcy. Reportedly 45,000 lbs of copper, valued at $9,000, had been taken from this mine. This mine was leased, but no further work was done. In 1957, Banner Mining Co. requested from the Bureau of Land Management 7,600 acres for an open pit over the Gould Mine area. Public outcry stopped further development. The area became part of Saguaro National Monument in 1963. All mining rights expired in 1975.

NPS Photo Lime KilnsThere are six lime kilns in Saguaro National Park (SNP) — four in the Rincon Mountain District (RMD) and two in the Tucson Mountain District (TMD). Lime was an important building material for any developing community. Many lime kilns were constructed in the mountains around Tucson, and as the town grew in the 19th century, so did the demand for lime. Lime kilns were usually built near the source of limestone, but may also have been built near the construction site. The earliest use of lime dates to present-day Turkey between 7,000 and 14,000 years ago, and many ancient civilizations used it to create mortar to hold stones together. The Romans, however, took lime a step further, mixing it with various other ingredients to create an early version of cement. |

Last updated: May 6, 2025