Have you ever heard the old saying, “A woman aboard ship is bad luck?” Back in the 1930s, that was one of the things Annette Brock Davis was told when she decided to set sail aboard a training ship. Luckily for us, she didn’t listen—and she wrote down her adventures where we can all read about them.

Annette’s mother was English, she married a Canadian and took her daughter back and forth in steamers on her frequent visits home. Annette went to school in Switzerland, Italy, and the French Riviera. By her early teens she had fallen in love with ships and sailing, was reading seamanship textbooks, and building scale models of them. She sold some of those detailed, well-crafted pieces and put the money away for the day she would find a way to go to sea. She spent some of this money to take a correspondence course in navigation, and later to attend a commercial sailor’s school in London.

We know her story in such detail because of her book, My Year Before the Mast. She wrote it in the last years of her life, with the encouragement of many. Her voice is clearly preserved, along with her unique experience of her time. Her story is at times, harrowing, victorious, and wise. She wrote from the perspective of a long life, well lived, and if you want to know more about her, I urge you to seek it out. You might find yourself dreaming of going to sea yourself by the time you finish it!

Annette made friends with Ben Davis, a young crewman on a Cunard Line steamer. He fell in love with her and they began writing to each other. When, in 1933, Annette got hold of a newspaper clipping about Betty Jacobsen, a secretary who sailed with Alan Villiers in the Parma, she immediately wrote to the Captain of that ship, and to Ben, asking him to visit Captain De Cloux on her behalf. She also sent Ben to the offices of the Erickson Line, the owners of that ship. In due course she received a telegram from them, and an offer of an apprenticeship.

Unlike the male apprentices, Annette’s contract did not contain the standard clause guaranteeing the trainee a job at the end of the apprenticeship, and the fee was twice what male apprentices paid. Also, at twenty-three years old, Annette had to get a signed statement from her father to prove he had given her permission to go. This was only the beginning of her challenges.

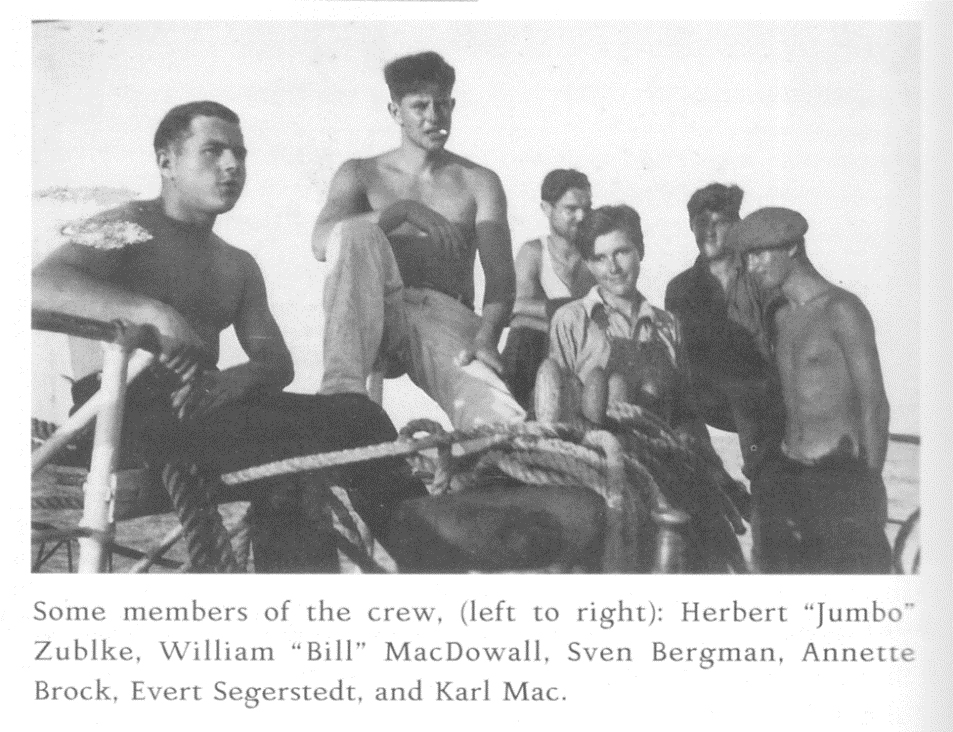

Annette faced a crew who didn’t want her there and made their displeasure clear. She was bad luck, and they didn’t expect her to work. In her place what might you have done? Annette had come too far to turn back, and she worked hard, first simply to be assigned meaningful tasks, and then to prove herself by doing them well. In the end, by hooking the flailing end of a staysail, a stupid and dangerous act, she won the respect of her shipmates and at last life aboard started to get better. By the time the ship reached Australia, Annette, now “Jackie,” was part of the crew.

At the end of the voyage, the ship was met by a reporter. When Annette tried to direct him to the Captain, she found that he’d come to see her. Without a second thought, she took the reporter aloft to get a good picture, and caught the crew looking up, laughing at their “girl apprentice” coaxing a terrified man up the rig. She suddenly realized just how far she had come and saw herself, at last, the equal of any man in the crew. Ben Davis met her at the ship and she traveled with him to London, where an even greater confirmation of her skill awaited: orders sent from the agents of the Erickson Line offering her a place as ordinary seaman in one of their vessels. Annette married Ben in secret, though, and when the shipping line found out, the offer was rescinded.

Annette Brock Davis was the quintessential exceptional woman. She had to be twice as capable as the men to get half as far as they did—and she managed to get a job as a professional mariner on her own merits. She overcame hardships that her shipmates never had to face, and got her foot on the first rung to her goal—a mate’s ticket, only to find it jerked out from under her for doing something women are now expected and encouraged to do; to have it all, a career and a marriage. She never questions her choices, though she does on many occasions question her competence. When every voice around you is telling you you’re in some way lacking, it’s hardly surprising that even a person who is sure of herself and her own mind might do the same. It is telling, in the end, that she had to be persuaded that her adventures were worth recording. You could do worse this Women’s History Month than to go down to your local library and read her story for yourself.