A century ago, Harry Dring was born. If you’ve never heard of him, you can be forgiven, but without him and his close friend Karl Kortum, there would be no historic vessels at Hyde Street Pier. Kortum, too, would have passed his century in this decade. The gift they gave to the world is still (mostly) intact. This is a minor miracle in this age, where we look always to the future and seldom to the past. This Park is often a surprise rather than a destination, but the tall masts are still a magnet to many and there are always some people who just have to set foot on these survivors from another age.

Harry Dring and Karl Kortum, as far as I can tell, shared that feeling. They were born at the end of an era, when the Oakland Estuary and Richardson Bay were choked with the last remnants of the Age of Sail. They probably met while exploring these vessels. Dring was lucky enough to be living near the Estuary, and he spent his time exploring those ships, making friends with the shipkeepers, and eventually helping out. He describes his involvement:

“I’d go down on a Saturday and work all day. I cleaned up, helped haul gear ashore, anything those old fellows wanted done. The shopkeeper might give me a quarter for a day’s work.” (Spectre 1983)

Kortum was a Sea Scout, and the writer of the pair. His papers describe himself and his friends in Petaluma working on boats, scrounging rides to the Bay from Petaluma for themselves and for various boats and bits of boats:

“Very sleepy after a night of turning and transferring eggs with Harvey, but we dashed home at seven to persuade Mr. King to drive the rudder [of our Sea Scout whaleboat] down to the train for shipment to Sausalito... We promised to have somebody there to receive it, otherwise it would be shipped back. Well, the four of us, in pairs, had very little luck getting rides and so when we saw the bus pull up in the street we telephoned from a service station to postpone shipment... On the road got a ride to San Rafael from a family and picked up the rudder to try the near impossibility of hitchhiking with it. Well, without effort, without thumbing, the first car with a pair of retired Vallejo sea scouts took us all the way. What luck!” (Kortum Papers)

As time passed, the friendship between the two, and their growing connections to the shipkeepers in Richardson Bay and Oakland led to the realization of their biggest dream; to sail around Cape Horn in a square-rigger. The first chance to sail in square-rig, in 1935, fell through. Captain Charles Watts, an experienced Cape Horn skipper, later to take the PACIFIC QUEEN into San Pedro under full sail, was assembling a crew of twenty “sea-minded lads” to take the STAR OF ZEALAND to Japan, to be scrapped. Kortum wrote an impassioned letter to him, asking for a job. Watts answered him by postcard: “If you make as good a sailor as you are a letter writer, you will suit me.”(Kortum Papers) Dring was hired as well. Union protests created an impasse, and in the end, a Japanese crew took the ship to Japan.

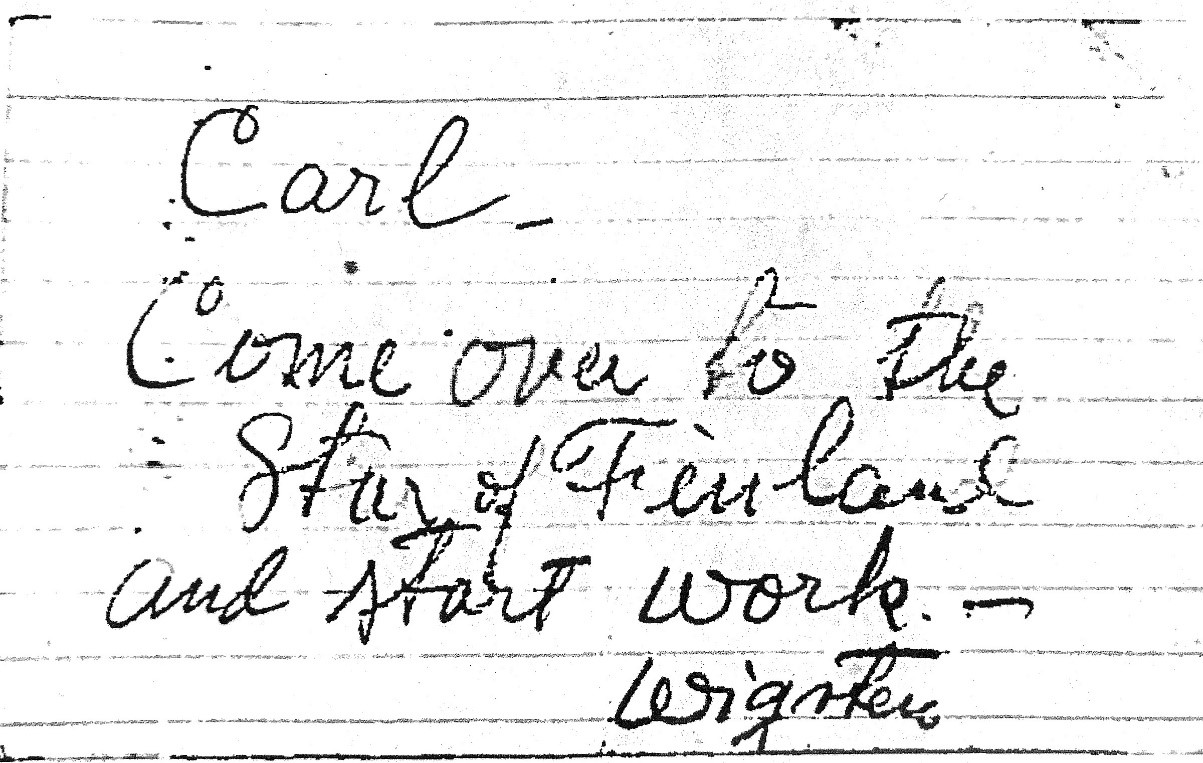

Six years later, however, Kortum received a handwritten note from another Cape Horn Captain, Hjalmar Wigsten:

It was 1941, and any vessel capable of moving freight across the ocean could find a cargo. The STAR OF FINLAND, her old name of KAIULANI restored, hired a crew that included Kortum and Dring and sailed for Aberdeen, Washington to load a cargo of lumber. The voyage took them around Cape Horn in the last commercial sailing voyage for a United States flagged vessel, and delivered it to Durban, South Africa. They talked of creating a museum full of ships, and what types of vessels would make the perfect candidates the whole way. The voyage ended in Australia. Dring returned to the United States and the Merchant Marine, and Kortum worked with the American Small Ship Service in Australia. When the war ended, he returned to the Bay Area, and together with other maritime enthusiasts, started the National Maritime Museum in the WPA building it occupies today.

The museum acquired BALCLUTHA in 1954, and when Dring ended a voyage in San Francisco, Kortum was waiting for him:

“Karl says ‘I want you to come over and see the BALCLUTHA.’ I said, ‘You dizzy son of a b—, I don’t want to see any more goddamned ships. I’ve had enough ships to last me forever.’ Three days later I was working on the BALCLUTHA.” (Spectre 1983)

More vessels followed, of course, and the park passed from private hands into the California State Park system, and from there to the National Park Service. We are privileged today to have these national treasures in our collection, and we owe it all to two boat-crazy boys who managed to realize a dream that became the work of their lives back in the days when these historic vessels were expensive white elephants. They pioneered the business of whole ship preservation and that fragile sliver of time they inhabited has many lessons to teach us if we realize, as they did, that it is not only worthy of preservation, but that doing so is no less than our duty to the future.

Sources:

"Give 'em Hell, Harry," Peter H. Spectre, Wooden Boat No. 61, 1983

Kortum Papers HDC 1084, Box 1, Series 5, Subseries 1 File 5

|

September 12, 2019

|

Last updated: September 12, 2019