Brassbounders in Training

Title:Monongahela (built 1892; bark, 4m: training ship) view on board showing apprentices watching demonstration of sail mending, undated

Credit: U.S. National Park Service

The age of sail training was built on the age of sail that preceded it. In this post we’ll explore two of the traditions that allowed commercial sail to survive and evolve into the vibrant world of ships and sailors that are still carrying cargoes of skill, memory and adventure today.

Racing to be the first vessel into port was a longstanding tradition. When people arrive at our park they often point excitedly at the “clipper ship,” a type of vessel that remains so famous it has come to stand for all sailing ships, though there is only one remaining vessel that can be visited, the Cutty Sark, in Greenwich, England. Our Balclutha no doubt appreciates the compliment, but she comes from a more prosaic age. The true clippers, designed for speed and carrying light, expensive cargoes like tea were born in the eighteenth century. They did race to be the first ship in port, for the first vessel in got the best price for their cargo. People bet on the outcome of these races, and these ships were front page news. By the nineteenth century, ships and their captains were known, and their careers were followed as avidly as any sports team of today. These courageous captains could take risks, and did, and until the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 opened a shorter route for steamships, clippers were the epitome of the sailing vessel.

By the early twentieth century, the Australian grain trade was the only seasonal cargo left to sailing ships—and therefore the only possible candidate for racing. Unlike the daring captains in times past, the masters of grain ships had to walk a tightrope between making the best time and keeping their owners ships, spars, and canvas in one piece. Officially, there was no such thing as a grain race, but being the first ship in port still mattered, and in 1928 the International Paint Company put up a silver cup for the winning vessel. Her name was Herzogin Cecilie, a vessel that you will learn more about in the next installment of this series. This vessel was heavily involved in sail training, and Alan Villiers book Falmouth For Orders is the story of that 1928 race. The Joseph Conrad, which he later owned and operated as a sail training vessel is still a seagoing summer camp at Mystic Seaport.

Traditionally, the large commercial sailing lines carried paid apprentices; the "brassbounders.” You can visit their sleeping quarters in the starboard side of Balclutha’s fore deckhouse today. These boys had families who could afford to pay for an apprenticeship so they could be trained as the next generation of officers, and they did the work of sailors before the mast as part of a thorough grounding in all aspects of seamanship. The training and conditions varied greatly from ship to ship. At one extreme, apprentices were trained in navigation and generally insulated from danger, and at the other, apprentices were essentially more foremast hands, standing watch, working, and braving Cape Horn as the sailors in the fo’cs’le did.

The Brassbounder, a novel written by Captain David Bone and available on the Project Gutenberg website, is a period piece in every sense of the word. Written in 1910 and based at least in part on the author’s voyage as an apprentice, it provides detailed descriptions of life aboard ship and of the San Francisco waterfront of 1889. It is marred by overt racism and dialogue written in dialect, but even those shortcomings provide a valuable record of the realities of nineteenth century life in sail. The boys of the City of Florence, a vessel that did indeed exist, are essentially paying to be sailors with a contract that guarantees their eventual advancement to officer rank when their apprenticeship is completed.

As time passed, and steam continued to encroach on the carrying of passengers and cargo, cutting each year more deeply into the sailing ship’s bottom line, some nations continued to require an apprenticeship in sail to become an officer in the merchant service. By the early twentieth century, the thrifty firms that served this need were able to keep their businesses viable by gaining not only apprenticeship fees, but what amounted to free labor from these boys who came to learn the ropes and start a career. In addition, some ships carried passengers who wanted to travel by sail, further sweetening their bottom line.

The next installment of this series will introduce you to the lively memoirs of the boys—and girls—who sailed before the mast for adventure, to test themselves in the rough school of the fo’cs’le and to make the trip around Cape Horn while they still could. The great age of commercial sail was ending, and people like Alan Villiers and Irving and Exy Johnson were sharing their experiences in the pages of National Geographic, short films, and memoirs that are still available today. It was the sunset of what seemed at the time to be the last great frontier and it seized the imaginations of young people all over the globe, including Karl Kortum, the founder of San Francisco Maritime. We encourage you to sign yourself in on the ship’s Articles and climb aboard to be part of the adventure!

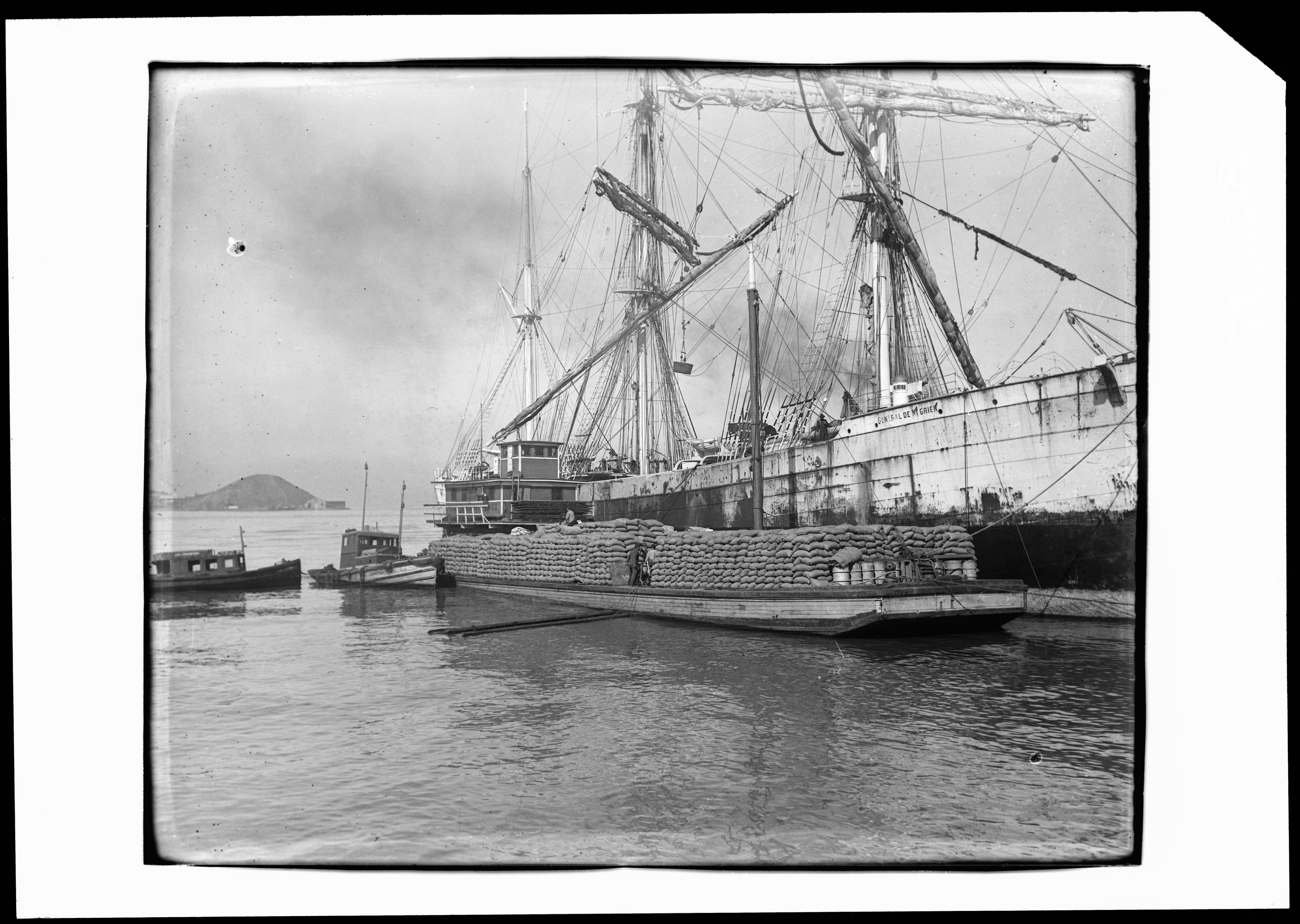

Loading Grain at the Oakland Long Wharf

Title: General De Negrier (built 1901; bark, 3m), loading grain at the Oakland Long Wharf, undated

Credit: U.S. National Park Service