-Ivan F. Cox, ILWU Local 38-79

“What is actually in progress there is an insurrection, a Communist inspired and led revolt against organized government. There is but one thing to be done – put down the revolt with any force necessary.”

-Los Angeles Times

May 9 marks the 85th anniversary of the beginning of the largest labor strike in West Coast History, when in 1934, longshoremen up and down the West Coast went on strike. It also marks the emergence of one of the nation’s significant labor leaders, Harry Bridges. On that day, longshoremen walked off the job until July 31 along the entire West Coast. In San Francisco, it stretched into a general strike which shut down the city and brought the strike into arbitration. The longshoremen won most of their demands, and emerged in the public eye from being viewed as lowly “wharf rats” to becoming respected “lords of the docks.”

The two quotes above encapsulate the two dominant and diametrically opposed views of the strike. Every major newspaper that reported on the strike shared the view of the Los Angeles Times editorial, as did elected officials and police departments. Those opposed to the strike and to radical unionism saw the strike as a life and death struggle between capitalism, and communism and chaos. Labor saw the strike as a battle for decent wages, and hiring practices, working conditions, union rights (as opposed to the company union in effect), and human dignity.

The number one issue for longshoremen was their demand to replace the “shape-up” hiring system with a union hiring hall. If you were a longshoreman seeking work, imagine arriving at the docks in the early morning along with several hundred other men, waiting for the foreman to pick and choose who would work that day. Only a small percentage of the men would be chosen. If you had any union sympathies, or were deemed a “troublemaker,” you would not be chosen. If you had enough money to bribe him with bottles of wine, cash, or some other payoff, your chances were much better. This was the hated “shape-up” system of hiring, which was outlawed on the London docks in the 1890s, but still persisted on American docks. As one observer noted, “You could see the faces and the eyes of the men saying ‘I hope it’s me,’ and sometimes, if you were hungry enough, you’d scream out at the boss….That’s how hard and miserable they made the human race on this waterfront.”

Other issues included an end to the “speed-up” of cargo handling which created dangerous and exhausting working conditions, a raise in wages, and a 30-hour work week.

What changed public opinion in San Francisco to turn from fear and opposition to the strike, to support? The turning point was a mass funeral procession for two strikers who were shot and killed by police during riots when the city and California National Guard attempted to open the port by force. The funeral procession was a silent march along the Embarcadero and up Market Street, with around 40,000 taking part. The general public was so moved by this scene, their perception of the strike and of longshoremen changed dramatically.

After the shootings, what came to be known as “Bloody Thursday,” a general strike was called, and much of San Francisco was shut down. After four days, the general strike ended and the longshoremen’s demands went into arbitration. The longshoremen won almost all their demands, and ports coastwise were unionized.

Park Ranger Peter Kasin presents a “table talk” on the strike. Come over anytime during this hour-long period to hear a talk and view books and photographs about the strike, this May 9, 3:30pm, and on other selected days, dates TBD. Please call the Visitor Center at 415-447-5000 for other dates, and see ticket booth on Hyde Street Pier for location (Table talk will be in the Visitor Center or on Hyde Street Pier depending on weather and wind conditions).

When looking at this historical event, we not only see a porthole into our past, but a continuum to our present. Issues around dignity of work, income inequality, Open Shop policies / union-busting and the place of unions in our economy and society give this history a sense of immediacy. Visitors at these table talks have often expressed passionate opinions for and against unions and strikes. Come discover this momentous event in West Coast labor history, ask questions and express your own opinions!

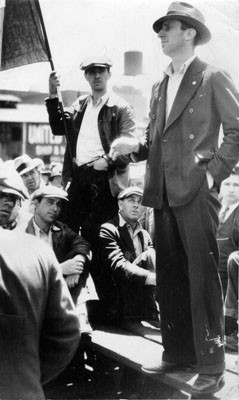

"Harry Bridges 1934 urging stevedores to Strike"

Credit: SFPL