|

New to Terry's Tidbits? Jump down to the Introduction. For recent Tidbits: Archived Tidbits: | |

|

October 15, 2009 Preparing for Winter Autumn comes early to the high Rockies. As early as August, plants and animals begin to prepare in various ways for the coming cold, snow, and high winds of winter. In essence, organisms can either settle in for the winter or flee to warmer climes, and if they stay, they can either sleep the winter away or stay active.

Photo courtesy of Rocky Mountain National Park

Animals don’t always survive hibernation. Recent research shows that mammals that eat human handouts during the summer are less likely to survive hibernation because the quality of fat stored is not as high as that on a natural diet. Another good reason to not feed the animals!

Photo courtesy of and copyrighted by Ernie Bernard

Photo courtesy of Rocky Mountain National Park

Photo courtesy of Rocky Mountain National Park Your comments are welcome and may be posted on this website. To submit your comment by email, please click here.

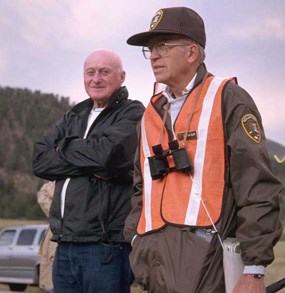

Photo courtesy of Rocky Mountain National park September 30, 2009 The Elk Bugle Corps Rocky Mountain National Park gets a huge influx of visitors during the elk mating season, also known as the rut. Elk are commonly seen in the park's meadows during the evenings, and visitors flock to observe them. So the park calls on the Elk Bugle Corps volunteers.

Photo courtesy of Rocky Mountain National Park The Elk Bugle Corps started in 1990. Each fall, about 90 volunteers give 2200 hours to the park. Every night during the rut, they go out in the park and talk with visitors who are observing the elk. They also help prevent traffic jams, a common occurrence on fall evenings. Sometimes visitors need a reminder that elk are wild animals, best observed from the road. The presence of the Elk Bugle Corps keeps visitors safe.

Photo courtesy of Rocky Mountain National Park The volunteers also teach visitors about elk ecology. When bus tours are offered, Corps members narrate the talks. They also give formal programs at the amphitheater in Moraine Park. And of course they have informal conversations with roadside visitors. So, when you come to the park this fall, give a salute to the Elk Bugle Corps volunteers. Want to join next year? Better contact the volunteer office now. It is a very popular job. For more information on the elk rut, click here. Your comments are welcome and may be posted on this website. To submit your comment by email, please click here.

Photo courtesy of Rocky Mountain National Park September 16, 2009 Green Fades to Gold Unusually mild weather and an abundance of rain may slow the color change in aspen in the lowest elevations of Rocky Mountain National Park.

Photo Courtesy of Rocky Mountain National Park What causes this shift of colors as the weather cools and days shorten? Chlorophyll is the green pigment responsible for the green color in plants and for most of the photosynthesis or food production in plants. As temperatures cool at night, plants start to break down chlorophyll and pull its building blocks back into the trunks and roots, conserving these vital resources for the future. However, other "accessory" pigments in the leaves are not broken down and stored. Accessory pigments are masked by chlorophyll in spring and summer, but remain to color the leaves in the fall. In aspen, the main accessory pigments are yellow and orange carotenes - the family of pigments that give carrots their distinctive orange color. In other plants such as wild geraniums, anthocyanins - red pigments - function as accessory pigments and provide the distinctive red fall colors. Accessory pigments capture light from other parts of the spectrum than that captured by chlorophyll, and thus make plants more efficient at making their food.

Photo Courtesy of Rocky Mountain National Park You may wonder why the aspen trees you see in suburban yards seem to turn colors independent of one another, while whole clumps of aspens in the park seem to turn color at once, while other clumps turn earlier or later. In suburban yards, each aspen tree is usually an independent plant put in place by the home owner. Aspens in the wild reproduce by sending out underground shoots more often than by seed. These shoots eventually pop up some distance away from the original aspen tree that produced them. This forms something we think of as a separate tree, but in fact, they are just stems of one plant. All these connected aspen stems, known more accurately as a clone, turn color and lose leaves in the fall in unison because they are one plant. The brief and brilliant season of fall is caused by processes as varied as its vibrant colors. Your comments are welcome and may be posted on this website. To submit your comment by email, please click here.

September 2, 2009 Clouds and Fog In Rocky Mountain National Park, a change of weather can be just a short walk away – which is why it’s so important to be prepared for any kind of weather. Just as boulders in a stream direct the flow of water over and around, so mountains direct air masses.

NPS Photo If the air is stable and the wind flow is strong, we’ll see lenticular clouds – also called lens clouds, cap clouds, or “flying saucer” clouds. These wonderfully unique clouds are common along the eastern slopes of the Rockies, especially in the wintertime when high winds aloft crest the continental divide and then sweep outwards towards the plains. Unlike other clouds that are blown along by the wind, lenticular clouds do not move because they form as the air rises and dissolve as it descends in the "bounce."

NPS Photo Differences in the heating and cooling of mountain slopes also affect cloud formation. Solar radiation increases with altitude (which is why sunscreen is so important when you hike in the mountains). Surfaces exposed to the sun rapidly heat up, and those not exposed stay cool. This can result in dramatic difference between sun and shade. In some areas the difference may be as great as 40 -50°F. On sunny days, upslope air flows develop due to this differential heating. These rising plumes of air are especially noticeable in the summertime and are responsible for our afternoon thundershowers. At night, the mountains cool quickly because of the thin, dry air. The cool air descends the slopes forming drainage flows that accumulate in valleys. If moisture is present, this cool, sinking air can cause local night-time valley fog. Your comments are welcome and may be posted on this website. To submit your comment by email, please click here.

August 12, 2009 Acute Mountain Sickness Every year, rangers in Rocky Mountain National Park treat countless park visitors with headaches, nausea, dizziness, and a host of other ailments. Many of the people they are treating are suffering from Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), a generic label applied to symptoms commonly experienced by people visiting high altitudes. The people treated by the rangers aren’t all rock climbers and mountaineers. Many of them are simply enjoying an easy hike or leisurely drive through the park with their family or friends. When travelling above 8,000 feet, everyone is susceptible to AMS.

As a person ascends through the atmosphere, every breath contains fewer and fewer molecules of oxygen. The body’s efforts to compensate for the reduced atmospheric pressure and a lower concentration of oxygen result in the symptoms associated with AMS. In order to avoid worsening symptoms, learn to recognize early signs of AMS. Symptoms of mild AMS include mild headaches, increased breathing, rapid pulse, nausea, loss of appetite, lack of energy, and general malaise. These are warning signs not to go any higher than you already are. A person suffering from moderate AMS may begin vomiting, experiencing increased shortness of breath and a headache that doesn’t respond to typical pain relievers. If you or someone you are travelling with experience these symptoms, it is important to descend to lower elevations immediately. Spend at least a day at an elevation where you are comfortable before attempting to ascend again. If symptoms advance to a lack of balance or coordination, slurring of words, altered mental state, extreme shortness of breathe, a wet or rasping cough, or blue skin, the person may be experiencing severe AMS and their life may be in jeopardy. Go down immediately and seek medical attention.

High elevation travelers with preexisting medical conditions are in even greater danger. Conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and conditions affecting the brain, heart, and lungs are among those that may be aggravated by high altitude and can prove deadly in the mountains. Fortunately, AMS is extremely easy to treat if diagnosed in time. The most effective treatment is simply to GO DOWN. Your comments are welcome and may be posted on this website. To submit your comment by email, please click here.

Introduction Welcome to “Terry’s Tidbits!” This blog will provide a bit of information and some attractive pictures about a natural history topic, an answer to the "burning question of the week," or an event in the park. The original Weekly Tidbits were created by Terry, a former Resource Management Supervisor (now retired) at Rocky and members of her staff. This blog will provide a new home for these delightful short articles. We have specifically tried to size some of the more attractive large photos to be made into wallpaper for your computer screen (by right clicking on the picture and selecting "Save as wallpaper" or "Select as background"). As a result, we hope you find these Tidbits informative and useful. Come join us. Your comments are welcome and may be posted on this website. To submit your comment by email, please click here. | |

Last updated: February 24, 2015