Library of Congress Grant stated that the murder of surrendering African American soldiers at Fort Pillow on April 12 motivated him to issue a formal demand that Black and White United States soldiers receive identical consideration in their treatment and exchange as prisoners by the Confederacy. On April 17, Grant wrote to General Benjamin Butler – who was negotiating a resumption of prisoner exchanges – that “the status of colored prisoners” was a priority. He ordered that Butler should communicate the non-negotiable demand that “no distinction whatever will be made in the exchange between white and colored prisoners,” that “the same terms as to treatment while prisoners and conditions of release and exchange must be exacted… in the case of colored soldiers as in the case of white soldiers.” “Non-acquiescence by the Confederate authorities,” Grant declared, “will be regarded as a refusal on their part to agree to the further exchange of prisoners.”1 Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon responded with a refusal of the terms. “I doubt,” he said, “whether the exchange of negroes at all for our soldiers would be tolerated." Ominously, Seddon added, "As to the white officers serving with negro troops, we ought never to be inconvenienced with such prisoners.”2 Robert E. Lee, writing to Grant later in the year, indicated his willingness to include “all captured soldiers of the United States of whatever nation and color,” in exchanges, but complicated the matter by also communicating the contradictory stance that he did not believe anyone who was formerly enslaved warranted treatment as a prisoner of war. “Negroes belonging to our citizens,” he wrote, “are not considered subjects of exchange… they cannot be returned.”3 Grant's response was to inform Lee that "the Government is bound to secure to all persons received into her armies the rights due to soldiers. This being denied by you in the persons of such men as have escaped from Southern masters induces me to decline making the exchanges you ask."4 As such, according to Grant’s April 17 demands, the prohibition on formal prisoner exchanges continued, as it had since the first appearance of African American soldiers on the battlefields. Andersonville National Historic Site notes that “in May of 1863, the Confederate Congress passed a joint resolution that formalized [Confederate President Jefferson] Davis' proclamation that Black soldiers taken prisoner would not be exchanged. In mid-July 1863 this became a reality, as several prisoners from the 54th Massachusetts were not exchanged with the rest of the white soldiers who participated in the assault on Fort Wagner. On July 30, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued General Order 252, which effectively suspended the Dix-Hill Cartel [prisoner exchange agreement] until the Confederate forces agreed to treat Black prisoners the same as White prisoners. The Confederate forces declined to do so at that time, and large-scale prisoner exchanges largely ceased by August 1863.” When Ulysses Grant took command, he was tasked with reevaluating this policy, and his April 17, 1864 order continued the Lincoln administration’s previous commitment. An often shared quote (linked here: https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/grant-and-the-prisoner-exchange.htm) is sometimes cited as evidence that Grant based the decision of halting prisoner exchanges on a callous mathematical consideration that doing so would win the war by attrition. Its timing is significant, as Grant made the referenced statement in August 1864, thirteen months after exchanges had already been halted on the basis of the Confederates’ refusal to acknowledge Black prisoners and four months after Grant stated the treatment of African American soldiers as his reason for continuing the prohibition on exchanges. 1 Ulysses Grant to Benjamin Butler, 17 April, 1864, Private and Official Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler (Norwood, Mass.: Plimpton Press, 1917), 83-84. 2 James A. Seddon to Howell Cobb, 13 June, 1864, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Recrods of the Union and Confederate Armies, Additions and Corrections to Series II - Volume VII (Washington, D.C.: the Government Printing Office, 1902), 204. 3 Robert E. Lee to Ulysses Grant, 3 October, 1864, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Recrods of the Union and Confederate Armies, Volume VII (Washington, D.C.: the Government Printing Office, 1902), 914. 4 Ibid.

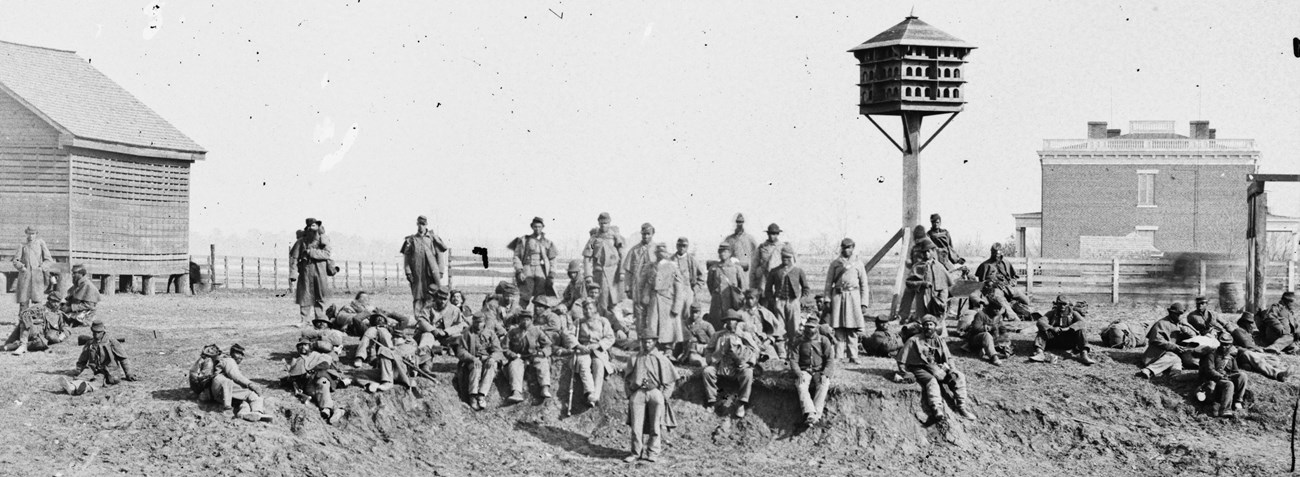

Library of Congress |

Last updated: November 30, 2023