NPS

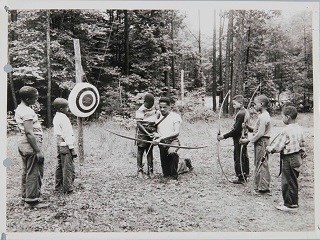

NPS Photo No account of Prince William Forest Park's early growth and development would be complete without giving recognition to the effects of segregation on the planning process. Prince William Forest Park was substantially developed between 1936 and 1950 in rural Virginia. Although the official policy of the NPS was one of non-discrimination deference was paid to "local custom" when developing parks in southern states. To understand the role segregation played in the development of the park it is necessary to identify the key decision makers. Critical input was provided by the NPS staff, camp users and, to a lesser extent, area residents. The NPS was divided into regions. Prince William Forest Park fell into Region One headquartered in Richmond, Virginia. Early in the planning process a tug-of-war developed between the Richmond office, headed by M. R. Tillotson, and the Land Planning Division of the NPS in Washington, headed by Conrad Wirth, assisted by Matt Huppuch. Mr. Tillotson felt very strongly that the planners of Prince William Forest Park recognize the

In contrast to Mr. Tillotson's views, Mr. Wirth was obliged to uphold the beliefs of his bosses, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, and Harry Hopkins, administrator of the FERA. Progressives formed in the same mold as President Roosevelt, Ickes and Hopkins fought for equal rights for blacks. Within the Interior Department, Ickes insisted

At issue were these two points: a) would the area be divided into separate camps for white and black and b) how would roads and entrances reflect the separation of the races. Caught between the Washington and Richmond offices were the two early managers of the area, William R. Hall and Ira B. Lykes. Hall and Lykes also came into contact with groups sponsoring organized camping in the park which constituted a third and equally forceful body of opinion. An incident occurring in July 1941 illustrates the attitudes of many park patrons. Contrary to policy, someone in the office of the superintendent of the National Capital Parks issued a permit for the Girl Scouts of Washington, D. C., to use an unused portion of Cabin Camp Two housing the Girl Scouts of Arlington, Virginia. Wisely, Miss Eleanor Durrett, director of the Girl Scouts of Washington, D. C., wrote a letter to Miss Ida Fleckinger, camp director for the Arlington Girl Scouts, requesting her permission to use the vacant cabins in Unit C. Miss Fleckinger promptly reminded Ira Lykes that

Clearly, the "customs of the people" were incongruous with the principles of equal opportunity upheld by Secretary Ickes, to the vexation of Hall and Lykes. The issue of racial segregation was most hotly debated between 1935 and 1939 when the cabin camps were being constructed. No one wished to be drawn into a controversy over segregation, aiding the search for a workable compromise. What developed was an interesting divergence between policy and practice about which little was said. As can be seen on the 1939 Master Plan, the area was divided into separate sections for white and African American campers. The cabin camps were numbered in the order in which they were built. Camp One was built in the section set aside for African Americans and the facilities were designed to meet the needs of underprivileged African Americans in Washington, D. C. Official recognition could not be given to this arrangement, therefore responsibility for the racial composition of the camp was assigned to the "maintaining agency" as follows:

Thus, by placing access to the cabin camps under the control of the organizations using the facility Wirth was able to bow to prevailing racial attitudes without officially endorsing racial separation. By 1942 Camps One and Four had become known as African American camps and Camps Two, Three and Five as white camps. Debate over the placement of the entrance road delayed the construction of other key buildings in the park. The superintendent's residence, park headquarters, and a permanent utility area could not be located until the location of the entrance road was finalized. A decisive meeting was held on October 4, 1939. It was determined that one entrance from Dumfries, Virginia, would be built at the intersection of Route 1 and Route 629. The entrance road would follow Route 629 for a short distance to a one-point control circle at the intersection of the main entrance road and the roads to the day use and organized camps. Actual construction was delayed until the right of way could be purchased and the necessary funds appropriated. (See Chapter Four for acquisition details.) Elated by the breakthrough Inspector Ray M. Scheneck, who had worked on the park steadily since its inception, suggested "October 4 should be declared as a day of annual celebration for the Chopawamsic Area " and an open house "should be held on that day." An apparent victory for the Washington office, this decision was actually a well disguised compromise. Pending completion of the entrance road there would be two effective entrances: one off Route 234 into the black camping and day use area and one off Route 626 and Joplin Road into the white camping and day use areas. The lack of funds for land acquisition and road construction brought on by the pending involvement of the U. S. in World War II meant the single entrance road so detested by the Richmond office was far from becoming a reality. Regardless, Wirth could point to the absence of discrimination in the official design of the park. The road was built in 1951. The battles waged between the Washington and Richmond offices of the NPS over camp facilities and access roads had little bearing on the day usage of the park. This is not to suggest that racial prejudice did not exist in Prince William County. Simply stated, from 1935 to 1950 there were no day use facilities to speak of in the park. The Pine Grove Picnic Area was not constructed until 1951. The few roads in the park were made of rough gravel, uninviting to motorists. Casual sightseeing was further discouraged by signs which read "Federal Reservation. Closed except to persons holding camping permits." Were that not sufficient to deter the curious, recent memory of the OSS occupation was enough to convince the local population that the park was off limits. |

Last updated: October 1, 2024