Last updated: July 30, 2024

Person

Yuri Kochiyama

Courtesy of the Kochiyama family/UCLA Asian American Studies Center

Yuri Kochiyama was a Japanese American political and civil rights activist. During World War II, the U.S. government forcibly removed her and her family to an incarceration site for Japanese Americans. For fifty years, Kochiyama spoke out about oppressive institutions and injustice in the United States. Her activism supported the liberation and empowerment of African Americans, Asian Americans, and Puerto Ricans. She also advocated for nuclear disarmament, reparations for Japanese American incarcerees, and the release of prisoners whom she regarded as prisoners of conscience.

When is it necessary to challenge the status quo? What would drive you to do so?

Activists are people who want to challenge the status quo. They often face backlash and resistance. As a radical activist, Kochiyama supported many controversial causes. Many people have criticized her admiration for figures who challenged or opposed the U.S. government, including foreign adversaries like Osama bin Laden. With awareness of Kochiyama's controversial stances, this article recognizes her activism in the struggles for rights for people of color.

Early Life and Incarceration

Yuri Kochiyama was born Mary Yuriko Nakahara on May 19, 1921. Her parents were first-generation Japanese immigrants. As a child and young adult, Kochiyama was active in her school and community.

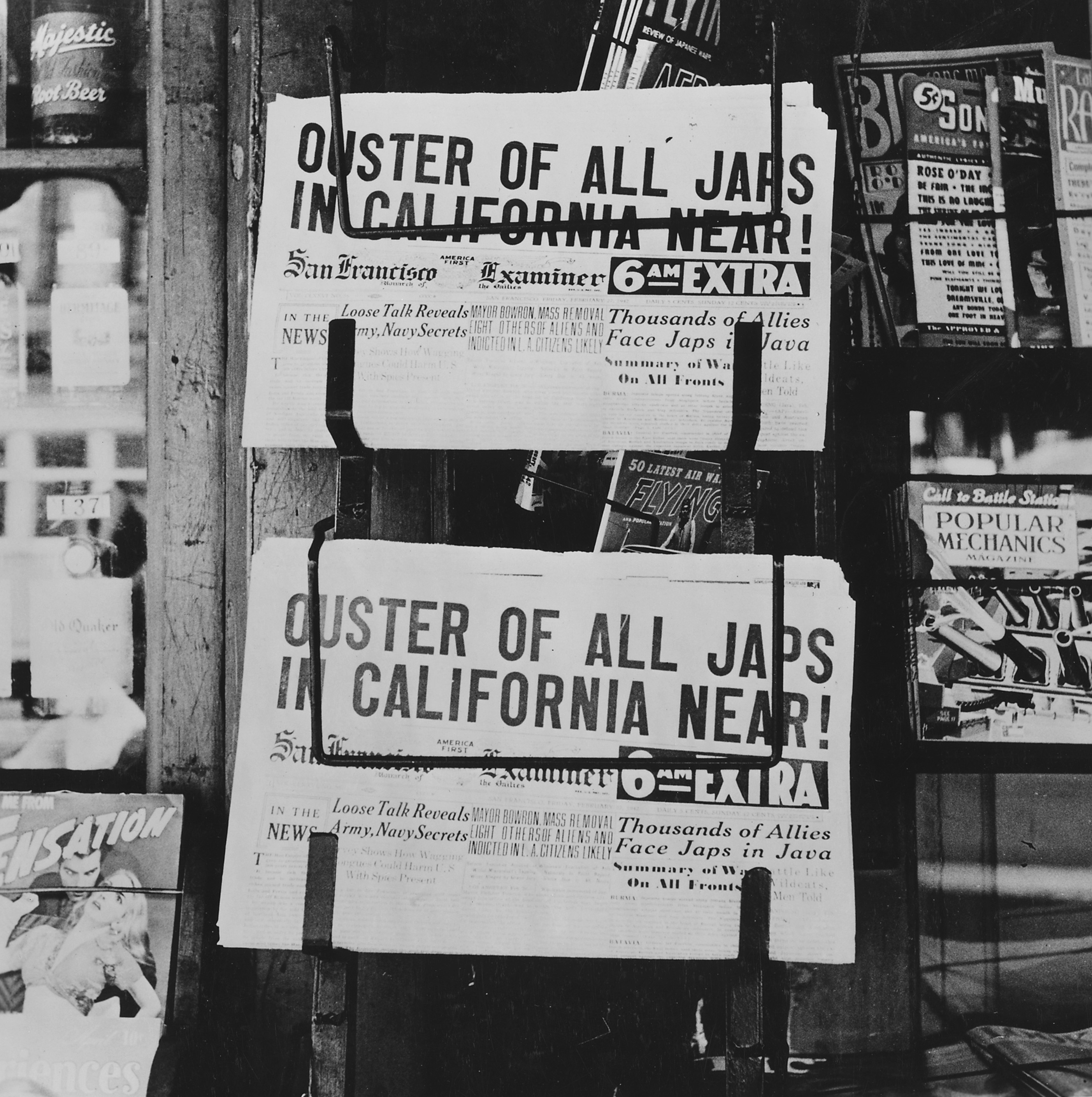

Her life changed after Japan bombed the American naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawai‘i on the morning of December 7, 1941. Congress quickly declared war on Japan and the U.S. formally entered World War II. Fearful that Americans of Japanese descent would side with the Japanese, President President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. This presidential act forced Japanese Americans to relocate to incarceration sites, even if they were American citizens.

Later on December 7, the FBI arrested Kochiyama’s father and other first-generation Japanese Americans as “national security threats.” Although he was recovering from a recent ulcer surgery, the authorities refused to provide medical treatment. When Kochiyama's father was released six weeks later, his health had deteriorated rapidly. He died within one day of returning home.

Soon after, the government temporarily detailed Kochiyama's family at the horse stables at the Santa Anita racetracks near Los Angeles, California. For most of the war, they were incarcerated at a confinement site in Jerome, Arkansas.[1] In her diary, Kochiyama maintained a positive outlook, but also described the anger of other incarcerees and her exposure to racism. Despite her confinement, Kochiyama urged other incarcerees to write letters of support to Japanese American soldiers serving in the U.S. military.

Soon after, the government temporarily detailed Kochiyama's family at the horse stables at the Santa Anita racetracks near Los Angeles, California. For most of the war, they were incarcerated at a confinement site in Jerome, Arkansas.[1] In her diary, Kochiyama maintained a positive outlook, but also described the anger of other incarcerees and her exposure to racism. Despite her confinement, Kochiyama urged other incarcerees to write letters of support to Japanese American soldiers serving in the U.S. military.

In 1944, Kochiyama volunteered to work at an all-Japanese, segregated United Service Organizations (USO) Center in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, so that she could get out of the incarceration site in Jerome. The USO Center provided programs and entertainment for active-duty service members at Camp Shelby Army Base. There, she met William “Bill” Kochiyama. Because Bill was Japanese American, he was incarcerated in Topaz, Utah.[2] He enlisted in the U.S. Army 442nd Regimental Combat Team to escape the confinement site and prove his patriotism. Working at the USO in Hattiesburg, Yuri witnessed Jim Crow segregation for the first time. In this new context, she gained a new understanding of race that she did not have in California.

Early Activism

Yuri and Bill Kochiyama married in 1946. During their 47-year marriage, they raised six children and supported several activist causes. The Kochiyamas moved to the Amsterdam Houses near Lincoln Center in New York City. In December 1960, they moved into the Manhattanville Housing Projects in Harlem. Living and working in Harlem exposed them to the Black and Puerto Rican communities’ struggles for freedom, which sparked Kochiyama’s interest in civil rights activism. In 2004, she explained:

“I didn’t wake up and decide to become an activist. But you couldn’t help notice the inequities, the injustices. It was all around you.”

Known as “Grand Central Station” or the “Revolutionary Salon," Kochiyama's apartment in Harlem became a crossroads for activists, artists, and intellectuals. Kochiyama also became well known for her behind-the-scenes work. She made flyers, wrote newsletters, and corresponded with prisoners in the Black freedom struggle and other movements. Knowing how important morale was for a movement, Kochiyama encouraged other activists to send birthday cards and care packages to prisoners, not just demonstrate outside of detention facilities.

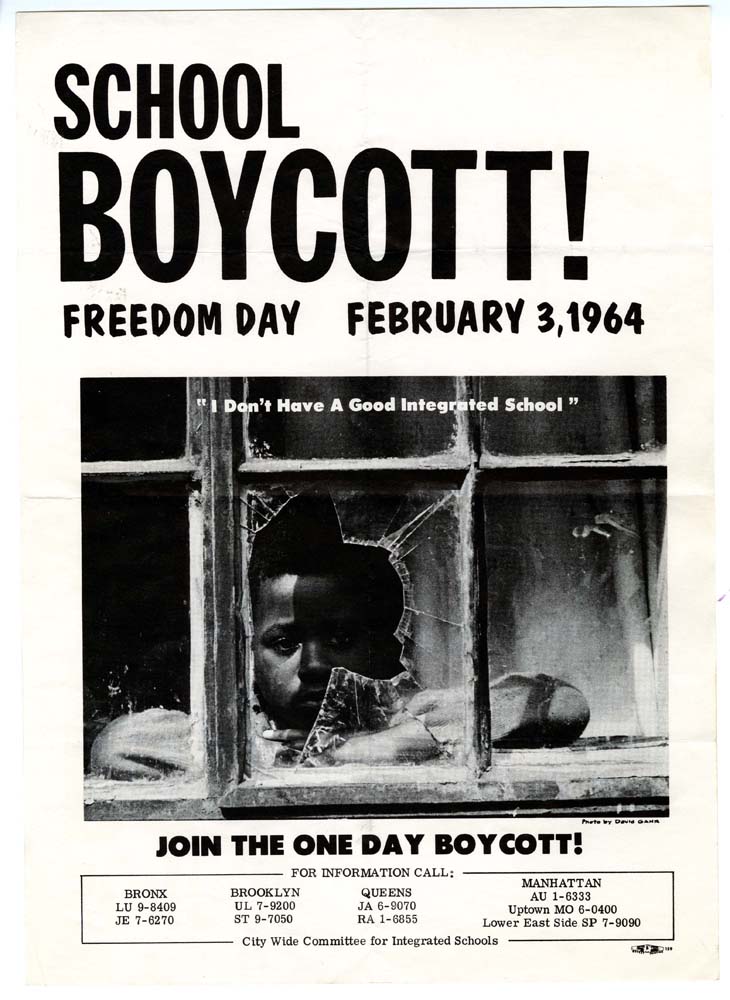

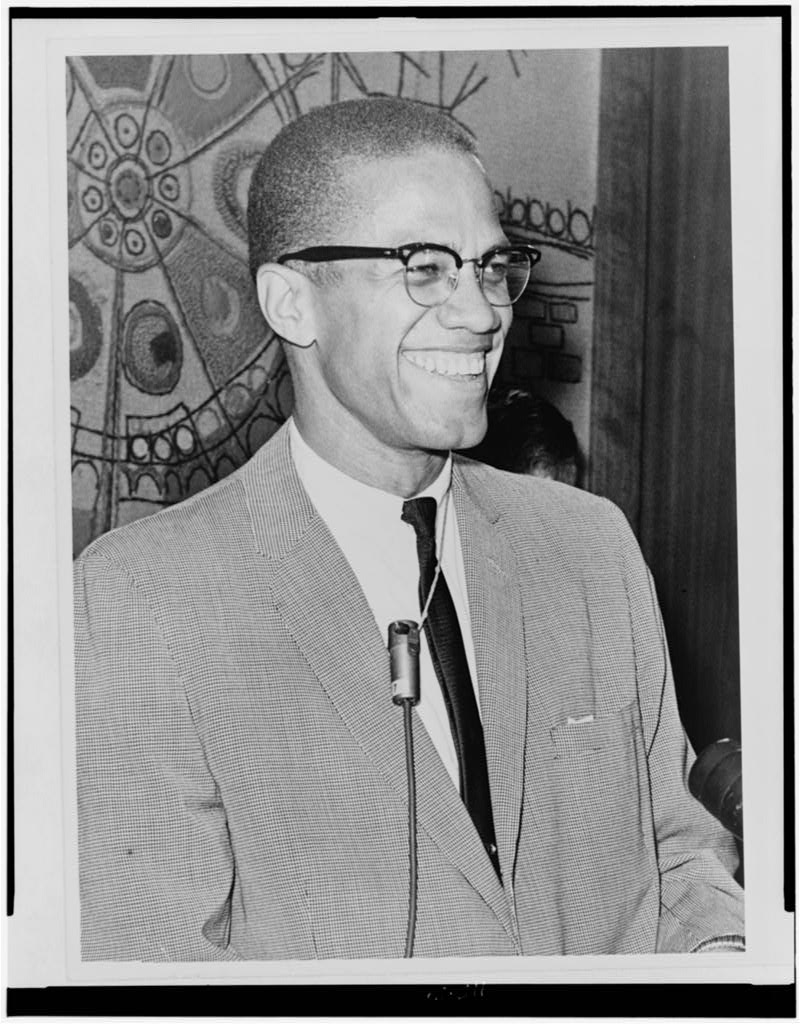

The Impact of Malcolm X

Meeting Malcolm X in October 1963 transformed Kochiyama's approach to activism. She, Bill, and their oldest children had enrolled in the Harlem Freedom School and participated in the 1964 New York City school boycott to protest the segregation of public schools. Their oldest son, Billy, also traveled to the South as a Freedom Rider during the 1960s.[3] But until Kochiyama met Malcolm X, she advocated simply for racial integration. Malcolm X encouraged her to develop an internationalist and anti-imperialist view, linking the freedom struggles of Black people in America with the experiences of people of African and Asian descent all over the world.

She, Bill, and their oldest children had enrolled in the Harlem Freedom School and participated in the 1964 New York City school boycott to protest the segregation of public schools. Their oldest son, Billy, also traveled to the South as a Freedom Rider during the 1960s.[3] But until Kochiyama met Malcolm X, she advocated simply for racial integration. Malcolm X encouraged her to develop an internationalist and anti-imperialist view, linking the freedom struggles of Black people in America with the experiences of people of African and Asian descent all over the world.

After attending Malcolm X’s Liberation School and becoming involved with his non-religious Organization of Afro-American Unity, she embraced his viewpoint of "human rights" rather than civil rights. In a 1965 interview, Malcolm X explained the difference:

"We believe that our problem is one, not of violation of civil rights, but a violation of human rights. Not only are we denied the right to be a citizen in the United States, we're denied the right to be a human being."

Furthermore, “human rights” reflected the need for the recognition and respect of Black people around the world, not just in the United States.

On June 6, 1964, Kochiyama hosted a reception for the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Study Mission at her apartment. Despite her status as a newcomer to the Black freedom struggle, she invited Malcolm X to meet with sufferers of the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Due to his prominence as a Black nationalist leader, recent departure from the Nation of Islam, and constant attacks in the press, Kochiyama doubted he would come. When Malcolm X arrived, he spoke about his studies in prison, Chinese and Japanese history, and his opposition to the Vietnam War. He explained that the freedom struggles of people of color and third-world people were linked. Partially inspired by the connection between Malcolm's faith and activism, Kochiyama converted to Islam from 1971 to 1975.[4]

On June 6, 1964, Kochiyama hosted a reception for the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Study Mission at her apartment. Despite her status as a newcomer to the Black freedom struggle, she invited Malcolm X to meet with sufferers of the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Due to his prominence as a Black nationalist leader, recent departure from the Nation of Islam, and constant attacks in the press, Kochiyama doubted he would come. When Malcolm X arrived, he spoke about his studies in prison, Chinese and Japanese history, and his opposition to the Vietnam War. He explained that the freedom struggles of people of color and third-world people were linked. Partially inspired by the connection between Malcolm's faith and activism, Kochiyama converted to Islam from 1971 to 1975.[4]

Kochiyama and her 16-year-old son Billy were also present when Malcolm X was assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom on February 21, 1965.[5] Even after the assassination, the Kochiyama and Shabazz families remained close. Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz’s eldest daughter Attallah was a frequent guest at the Kochiyama house.

Liberation and Self-Determination

Malcolm X’s encouragement to know oneself and one’s history helped to change the way Kochiyama viewed power and racism. Fueled by opposition to the Vietnam War, she became a pioneer of the Asian American movement. In 1969, she and Bill joined the new organization Asian Americans for Action (AAA), which drew inspiration from the Black Power and anti-war movements. Kochiyama became a featured speaker at the AAA’s Hiroshima-Nagasaki Day events. She later championed the development of ethnic studies programs and reparations for former Japanese American incarcerees.

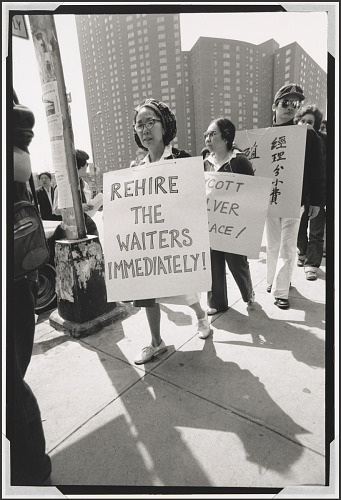

During the 1960s and 1970s, Kochiyama advocated for Puerto Rican self-determination. In 1969, she joined the Young Lords’ Party, a civil rights organization committed to Puerto Rican independence. In October 1977, Kochiyama participated in the takeover of the Statue of Liberty by Puerto Rican Nationalists. Thirty demonstrators ocupied the monument, climbed to the top, and hung a Puerto Rican flag from Lady Liberty's crown.

Throughout this period, Kochiyama remained committed to the Black freedom struggle. She worked with Black Power and Black nationalist organizations including the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika. This organization advocated for self-determination, reparations for slavery and segregation, and the creation of an independent Black republic in the southeastern United States. She also advocated for the release of Black prisoners, including Mumia Abu-Jamal. Abu-Jamal was a former Black Panther and journalist who was accused of killing a police officer.

After Bill’s death in 1993, Yuri Kochiyama moved to Oakland, California to live with her daughter. The focus of her work shifted to the war on terror. Kochiyama strongly condemned the rise in Islamophobia after the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001. At a peace vigil and rally in San Francisco’s Japantown, she drew from her experience with incarceration after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in her speech. She cautioned people not to give into fear and hate and to stand in solidarity with Arabs, Muslims, and South Asian people who were being victimized. She declared:

“In war, they say that the first casualty is truth. America forgot that we are American citizens. We Japanese Americans should feel a kinship with the Arab and Muslim people who are the newest targets of racism, hysteria, and jingoism—something that we have experienced too.”

After over fifty years of activism to end war, racism, and hatred, Yuri Kochiyama died on June 1, 2014 at the age of 93.

Notes

[1] Congress created the Japanese American Confinement Sites (JACS) grant program in 2006. The program awards grants for the preservation and interpretation of confinement sites where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II. Although the incarceration site at Jerome, Arkansas is no longer physically extant, the University of Arkansas received a JACS grant for digital storytelling and preservation projects related to the sites in Jerome and Rohwer, Arkansas.

[2] The Central War Relocation Center (Topaz) was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 2, 1974 and designated a National Historic Landmark on March 29, 2007.

[3] Freedom Riders National Monument is located in Anniston, Alabama.

[4] For more information, see Diane Carol Fujino, Heartbeat of Struggle : The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama (Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press, 2005), 210-211.

[5] The Audubon Ballroom is now known as the Malcolm X & Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center.

Bibliography

CBC. “Malcolm X on Front Page Challenge, 1965: CBC Archives | CBC.” YouTube Video, 7:48. April 7, 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C7IJ7npTYrU&t=3s.

Democracy Now! “Civil Rights Activist Yuri Kochiyama on Her Internment in a WWII Japanese American Detention Camp & Malcolm X’s Assassination.” February 20, 2008. https://www.democracynow.org/2008/2/20/civil_rights_activist_yuri_kochiyama_remembers.

Fujino, Diane C. “Kochiyama, Yuri.” Asian American Society: An Encyclopedia. Edited by Mary Yu Danico. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2014.

Fujino, Diane C. Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press, 2005.

Harlem World Magazine. “The Passionate Harlem Activist Yuri Kochiyama, New York, 1921 – 2014 (Video). Published July 7, 2020. https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com/harlem-activist-yuri-kochiyama-ny-1921-2014/.

Kochiyama, Yuri. “The Impact of Malcolm X on Asian-American Politics and Activism.” Latinos, and Asians in Urban America: Status and Prospects for Politics and Activism. Edited by James Jennings. London: Praeger, 1994.

Kochiyama, Yuri. “Yuri Kochiyama in Response to 9/11.” Apex Express, 94.1 FM KPFA. June 7, 2014. https://apexexpress.wordpress.com/2014/06/07/yuri-kochiyama-in-response-to-911/.

R Tajima. “Yuri & Bill Kochiyama: on the road in Mississippi.” YouTube Video, 9:01. June 2, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ApSa2_SW9rw.

Swift, Jaimee A. “Celebrating 100 Years of Yuri Kochiyama: Akemi Kochiyama on Her Grandmother’s Life, Leadership, and Legacy.” Asian American Writers’ Workshop. May 19, 2021. https://aaww.org/celebrating-100-years-of-yuri-kochiyama/.

Woo, Elaine. Los Angeles Times. “Yuri Kochiyama, ‘60s civil rights activist and friend of Malcolm X’s dies at 93.” Washington Post. June 5, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/yuri-kochimaya-60s-civil-rights-activist-and-friend-of-malcom-x-dies-at-93/2014/06/05/1dbe93dc-eccd-11e3-b98c-72cef4a00499_story.html.

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson and updated by Maya Goldenberg, interns with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.