Last updated: January 6, 2026

Person

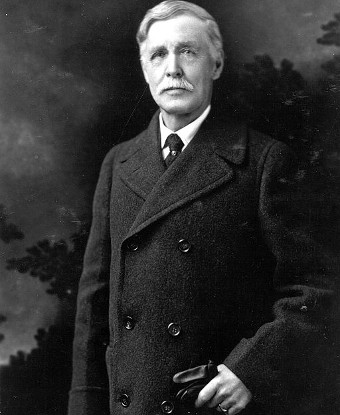

William Henry Jackson

USGS photo

William Henry Jackson is best known as the first person to photograph the wonders of Yellowstone. His images adorned the parlors of millions of American households and aided in the effort to create the world's first national park. Jackson was also an accomplished artist who recorded his experiences as a young man. His drawings and paintings provide valuable insights to life in a time when America was suffering through the Civil War and venturing westward in search of a national identity.

Growing up in Keeseville, New York, the oldest of seven children, William Henry Jackson was born to George Hallock Jackson and Harriet Maria Allen on April 4, 1843. Harriet was a talented watercolorist, and Jackson had the opportunity to learn from her at a young age. He spent much of his childhood mastering the arts of drawing and painting. At the age of 10, Jackson was given the book The American Drawing Book: A Manual for the Amateur by John Gadsby Chapman. From this book, Jackson learned how to use perspective and form, color, and composition. As a teenager, Jackson was introduced to photography in Troy, New York, and Rutland, Vermont. There, he worked as an assistant in a photographer’s studio, helping to stage and retouch photos. During this time, he learned how to use cameras and the darkroom techniques of the time.

Jackson might have continued to learn his trade and settle into a stable and lucrative career, but events beyond his control would soon take him in a new direction. In August of 1862, the 19-year old William Henry Jackson enlisted as a member of the Light Guard from Rutland, Vermont. With the exception of occasional guard duty, there was little for the aspiring artist to do. Jackson passed the long, boring hours sketching his friends and scenes of camp life to send home to show his family he was safe. In June of 1863, Jackson’s regiment participated in the climactic Gettysburg campaign, but never saw action in the battle. Soon after his term of enlistment expired, William Henry Jackson returned to civilian life. Luckily, his mother saved the pencil sketches created during his wartime service, and they survive today as a record of an infantryman’s life in the Union army.

On his return home, the young veteran quickly found employment in another photographic studio. His obvious skills won him a fine salary, which enabled him to buy fancy clothes and live the good life. After a year, during which he had received substantial raises and promotions, he became engaged to a young woman from a prominent family. Every indication pointed to a happy, successful life and career. However, a lover’s spat in 1866 brought Jackson’s world crashing down around him. Too ashamed to face his family after the breakup with his fiancé, the heartbroken young man decided to leave Vermont and seek his fortune in the gold mines of Montana. Jackson and two friends set out for the western frontier, making their way to Nebraska City, Nebraska Territory – a jumping off point for freighting caravans headed west. There the three young easterners signed on as bullwhackers for a freight outfit bound for Montana. Despite knowing nothing about oxen or hauling freight, Jackson soon grew proficient in handling the powerful draft animals.

The hard work and new country did much to mend Jackson’s broken heart. Soon he was back to his old habits of sketching the things he saw and the people he met. Forsaking his dream of striking it rich, Jackson left the freight train near South Pass in Wyoming and headed south for Salt Lake City and eventually California. His experiences in the West struck a chord in Jackson, and he began to realize that documenting the settling of the frontier might become his life’s work.

With assistance from his father, Jackson established his own photographic studio in Omaha, Nebraska in 1869. He began photographing American Indians from the nearby Omaha reservation and the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. These photographs came to the attention of Dr. Ferdinand Hayden, who was organizing an expedition that would explore the geologic wonders along the Yellowstone River in Wyoming Territory. Hayden realized that a photographer would be useful in recording what they found. Jackson was invited to participate in the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871. As a member of the survey, he observed and captured via photographs and paintings the wonders of the region that would become Yellowstone National Park. He served as official photographer for the US Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories until 1878.

Anyone else might have been daunted by the thought of transporting delicate camera equipment and glass plate negatives across the West, but Jackson’s experience as a bullwhacker would serve him well. The images he brought back caused a sensation. For many years, stories about geysers and waterfalls were thought to be tall tales, but Jackson provided proof of their existence. Public interest resulted in the U.S. Congress officially designating Yellowstone National Park in 1872, and Jackson’s name became a household word.

For the next seven years, Jackson worked with Dr. Hayden for the United States Geological Survey. The Survey took him to such unique and unexplored places as Mesa Verde and Yosemite, which Jackson documented with thousands of photographs.

One of his most famous images would be taken in 1873. For years, stories of a mountain with a large cross etched in its side had been circulating, but it wasn’t until Jackson risked climbing Colorado’s Notch Mountain in the heart of the Rocky Mountains for a clear photographic view that its existence was proven. Within a few months of the photograph’s publication, his image of the Mount of the Holy Cross adorned the parlors in thousands of American homes. Jackson’s work for the U.S.G.S. ended in 1878. He continued to work in the West, opening a studio in Denver, Colorado, returning to portrait photography as well as documenting railroad construction to mining towns in the Rockies.

At an age when most men have already retired, William Henry Jackson embarked on a new career. He chose to return to the paintbrush at the age of 81, working as a muralist for the new U.S. Department of the Interior. Jackson’s eye for composition, coupled with the fact that he had experienced the transformation of the West firsthand gave added credibility to his work. Soon his paintings of western scenes were in demand for illustrating books and articles. Jackson completed 100s of paintings, mostly dealing with historic themes such as the Fur Trade, the California Gold Rush and the Oregon Trail. Jackson revisited many of the sites he depicted in his paintings so he could paint them as accurately as possible. For those scenes that predated his own lifetime, he sought out and interviewed surviving participants.

William Henry Jackson died on June 30, 1942 at the age of 99 in New York City from injuries resulting from a fall. Recognized as one of the last surviving Civil War veterans, he was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. His long and active life paralleled the formative years in the life of the United States, and his many contributions as a soldier, bullwhacker, photographer, explorer, publisher, author, artist, and historian have left a lasting legacy that the National Park Service is proud to honor.

Mount Jackson, just north of the Madison River, in the Gallatin Range of Yellowstone National Park is named in honor of Jackson.

The archives of Scotts Bluff National Monument, in Gering, Nebraska, house the world's largest collection of original William Henry Jackson sketches, paintings, and photographs.