Last updated: January 12, 2026

Person

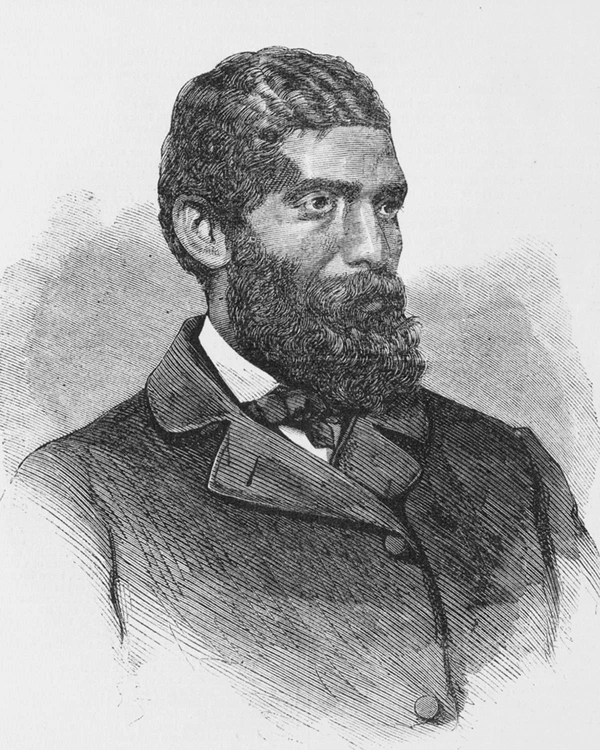

John S. Rock

Library of Congress

Dentist, doctor, lawyer, and activist John S. Rock1 fought against slavery and for the elevation of the Black community.

Born in New Jersey to free parents, John S. Rock received a strong education as a youth and carried that dedication to learning throughout his life. As a teenager, he became a licensed schoolteacher in Salem, New Jersey.2 Setting his eye on medicine, he apprenticed with two doctors but could not gain admission to any medical schools. Instead, he turned to dentistry.3 He then moved to Philadelphia to establish a practice.

In Philadelphia, Rock returned to his medical studies at the American Medical College. He graduated in 1852, becoming one of the first Black men to receive a medical degree.4 He offered night classes for Black students studying medicine.5 However, soon after completing his medical training, Rock's dental practice burned to the ground, which may have, in part, prompted his move to Boston.6

In Boston, Rock and his wife Catharine boarded at the home of Lewis and Harriet Hayden, two of the city's most prominent Black activists. He established a medical practice on nearby Cambridge Street and joined a local Masonic Lodge.7

Like he did in Philadelphia, Rock became involved in antislavery work in Boston as well. While living at the Hayden House, a major stop on the Underground Railroad, Rock provided medical assistance to freedom seekers escaping slavery. He also became a prominent public speaker on issues such as abolition and racial uplift and equality.8

As a speaker, he addressed the Massachusetts legislature on several occasions, including a lecture on the "Unity of the Human Races." He also argued for the elimination of the word "white" from state militia laws to open the doors to Black men serving.9

He traveled across the Northeast on his speaking tours and served as a delegate to the 1855 Colored National Convention and the National Convention of Colored Men. He also spoke in front of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and other abolitionist groups.10

In his speeches, Rock stressed Black pride and community uplift in the face of racial injustice and oppression. For example, in a speech at the annual Crispus Attucks Day celebration, Rock said:

I not only love my race but am pleased with my color...I shall feel it my duty, my pleasure and my pride, to concentrate my feeble efforts in elevating to a fair position a race to which I am especially identified by feelings and by blood.11

After receiving medical treatment in Paris, France in 1858, Rock returned to the United States and studied law. Admitted to the Massachusetts Bar in 1861, he opened his practice at 6 Tremont Street. Soon after becoming a lawyer, the governor and Boston city council appointed Rock to the position of Justice of the Peace for the City of Boston and Suffolk County.12

During the Civil War, Rock worked in Boston, Providence, and Philadelphia as a recruiter for Black military units, including the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. He saw Black military service as an integral duty of citizenship and as key to the advancement of the race. Speaking to the 5th US Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment, Rock said, "Remember that the colored soldier has the destiny of the colored race in his hands."13 He also worked as a claims agent to help widows and veterans win pensions for their services during the war.14

In 1865, Senator Charles Sumner presented Rock's credentials to the U.S. Supreme Court and Rock became the first African American admitted to the Supreme Court Bar. The U.S. House of Representatives soon thereafter received him on the floor, making Rock, again, the first African American to earn that distinction.15

After years of illness, Rock passed away on December 3, 1866, at the age of forty-eight. Reverend Leonard Grimes conducted his funeral services at the Twelfth Baptist Church where Rock had worshipped and spoken many times.16

His remain are buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts.

Footnotes

- Please note, different historians and sources indicate different middle names for Rock including "Sweat," "Swett," and "Stewart."

- Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (Penguin, 2012), 228; William Wells Brown, The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (James Redpath Publisher, 1863), 267. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/64883/64883-h/64883-h.htm; Clarence G. Contee, "John Sweat (sic) Rock, MD, Esq., 1825-1866," Journal of the National Medical Association 68 no. 3 (1976): 237.

- Wells Brown, The Black Man, 268.

- Contee, “John Sweat (sic) Rock,” 237.

- Kathryn Grover and Janine V. Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," Boston African American National Historic Site, (2002), 110.

- Jacqueline Jones, No Right to an Honest Living: The Struggles of Boston’s Black Workers in the Civil War Era (Hachette, 2023), 136.

- Contee, "John Sweat (sic) Rock," 238; Horton and Horton, Black Bostonians, 109; Grover and Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," 111.

- Grover and Da Silva, 111.

- Wells Brown, The Black Man, 268; "Speech of Dr. John S. Rock," The Liberator, March 2, 1860.

- James Horton and Lois Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc., 1999), 63., Contee, "John Sweat (sic) Rock," 239.

- Horton and Horton, Black Bostonians, 130; "Speech of Dr. John S. Rock," The Liberator, March 16, 1860.

- J Wells Brown, The Black Man, 268-9; Horton and Horton, Black Bostonians, 64; Jones, No Right to an Honest Living, 213; Wells Brown, The Black Man, 269.

- Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom, 283.

- Jones, No Right to an Honest Living, 292-95.

- Jones, No Right to an Honest Living, 297-98; Grover and Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," 111.

- Jones, No Right to an Honest Living, 375-6.