Last updated: February 20, 2025

Person

Henry Blake Fuller

Chicago History Museum

Henry Blake Fuller was a key figure in the Chicago Literary Renaissance, renowned for pioneering social realism in American literature. He is noted for being one of the first American novelists to explore homosexual themes in his 1919 book Bertram Cope's Year. Fuller had a complicated love-hate relationship with Chicago—clashing with its industrialization and commercialism. He frequently found solace at Indiana Dunes, which served as a retreat from urban life and a source for inspiration:

"A house of dreams untold – to look out over the tree tops and face the setting sun."

Early Life

Henry Blake Fuller was born in a house in Chicago on January 9th, 1857 where LaSalle Street Station is today. He was a third-generation Chicagoan; his grandfather was a successful merchant, and his father organized the city’s first trolley car system. H. B. Fuller was the last direct descendent of Dr. Samuel Fuller, a pilgrim who emigrated on the Mayflower and became a powerful deacon and the first physician at Plymouth Colony.Henry Fuller had a lifelong fascination for aquiring knowledge and reading books. Constance Griffin wrote in his 1939 biography on Fuller:

He attended Chicago’s South Division High School, where Alice Mabel Gray would attend some years later. He finished his primary schooling at Allison Classical Academy, a boarding school in Wisconsin where he resented having to room with loud and messy boys who interrupted his reading. His journals from his early years allude to his attraction to the same sex. He wrote an imaginary personal advertisment in his diary during his final year at the academy, which included: “I would pass by twenty beautiful women to look upon a handsome man. A man with a fine form, a beautiful head, and a handsome face is a feast for my eyes.”“From earliest childhood Fuller was a solitary figure. He was quiet and delicate, preferring the company of his books to the boisterous games of boyhood. His school days provide an illuminating picture of his intense and unboylike preoccupation with study, his unending striving for perfection, and the grim tenacity with which he held to his self-imposed tasks.”

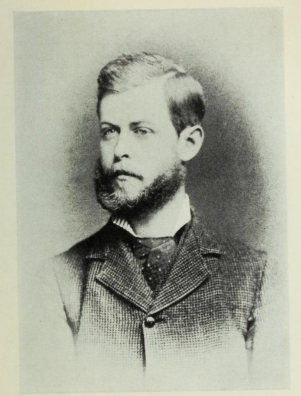

Image caption: Portrait of a young Henry Blake Fuller

Source: Tribute to Henry B. (1929) by Anna Morgan

Henry graduated in 1876 at the age of 19, and did not continue to university. For the next three years, Fuller held various desk jobs in Chicago, all of which he disdained. He spent a year at Ovington Brothers, another year as a messenger at the Bank of Illinois, and one more at the Home National Bank where his father worked. Fuller had a love-hate relationship with Chicago and its crass commercialism, stockyards, and dirt-spewing industries. He wrote that Chicago was "the only great city in the world to which all its citizens have come for the one common, avowed object of making money.”

Bored by the ruthless monotony of Chicago business, Fuller began making detailed plans for a trip to Europe, where he would collect experiences to write travel articles, at that time a very profitable and popular genre in American newspapers. In 1879, he set off for a year-long trip across Europe, spending time in England, France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and Holland. He kept detailed travel journals throughout his trip, and many of his notes during this tour were later repurposed when writing his first two novels.

Author

If he disliked Chicago before traveling abroad, he loathed it afterwards. During the next decade (1880-1890) between his first tour of Europe and his first novel, Fuller did not work many further desk jobs beyond tending to his family’s business matters after the death of his father in 1885. While living in his family home off LaSalle, he spent the majority of his twenties writing and traveling, including a second tour of Europe from April to September 1883, during which he revisited England, France, Italy and Switzerland. He then lived in Boston for a few months, drawn to the city’s arts, culture, and publishing, which he found depressingly absent from Chicago. In Boston and later at home in Chicago, he wrote articles, essays, ballads, burlesques, and even two light operas, which were never produced.

Image caption: Portrait of Henry Blake Fuller

Source: The Bookman, September 1895, New York

In 1886, as he was approaching 30 years of age, Fuller was working out of an office on Lake Street (it’s unclear whether he had taken a temporary desk job or if he was working on his family’s business). To ease a period of “considerable discomfort and depression,” one day he took an envelope out of his office wastebasket and wrote the opening lines of what would become his first novel, The Chevalier of Pensieri-Vani. He completed the manuscript in early 1887, and continued other writing pursuits over the next few years while trying to get it published. His first book was published in 1890, and his second, The Chatelaine of La Trinité, was published two years later in 1892.

Fuller's first two books drew from his travels to Europe. Set in Italy and the Alps respectively, both novels were short satires of late Victorian society that conveyed Fuller’s love affair with Europe, his disgust with American industrialization, and his contempt of hostility toward women.

H. B. Fuller was a sharp critic of the Chicago merchant-class social scene and an early environmentalist as he watched the increasingly polluted city eating up the prairie. He is considered a pioneer in social realism, a mode of writing that shows "things as they are" and paints reality in a stark, unadorned way. In Fuller’s writing, that involved depicting materialism in the city, exploitation of workers, and the role of commerce and industry in Chicago. The Cliff Dwellers, published in 1893, is considered one of Fuller’s best examples of realism. It takes place in a Chicago skyscraper and offers an unflattering portrait of money-centric, misogynistic businessmen and their wives.

Former Director of Studies at Newberry Library in Chicago, Liesl Olson, said: “I think Henry Fuller is the city’s first social realist, and social realism becomes a mode of critique that is distinctive to Chicago writers all the way into the twentieth and twenty-first century. So if you want to trace that literary history of social realism, Fuller is where you start.”

Homosexual Themes

In 1896, Henry B. Fuller published an anthology of plays in The Puppet Booth. Included was At St. Judas', which delves into the complexities of relationships, same-sex attraction and the struggles associated with it. It is thought to be the first play to explore homosexual themes. The play begins moments before a wedding. As the drama unfolds, we learn that the Best Man has secretly been trying to sabotage the wedding out of a deep love for the Bridegroom. The tragedy ends in suicide, underscoring the play's critical examination of societal pressures, moral hypocrisy, and the personal despair that can result from living in a repressive environment.The crumbling, handwritten manuscript of the play resides at the Newberry Library in Chicago. An analysis of the manuscript – the visible erasures, the inserted slips of dialogue, the dramatic alterations to the published text – reveals Fuller's intentional ambivalence in dealing with the theme of same-sex sexuality.

H. B. Fuller continued writing and publishing, but it would be over two decades before he returned to the taboo theme of homosexuality. In 1919, at age 62, Henry courageously released Bertram Cope’s Year; considered one of the first mainstream novels to depict a homosexual relationship. Fuller failed to find a commercial publisher and eventually a friend published the novel at his tiny Chicago-based Alderbrink Press.

In the philosophic novel, Bertram Cope is a handsome young college instructor who is befriended by a wealthy older woman who tries to match him with several eligible young women. However, Betram is emotionally attached only to his friend and housemate, Arthur Lemoyne. The novel’s portrayal of their relationship is subtle, but has clear overtones of sexual attraction.

Although the novel is valued today and described by modern critics as “Fullers best work,” it was mostly ill-received and ignored in his lifetime. His disillusionment over its reception drove him to destroy the manuscript and kept him from writing another novel for 10 years. In fact, though critically well-regarded, his books never sold well.

Death

Henry Blake Fuller died on July 28th, 1929 at age 72 due to a heart attack “aggravated by the heat.” He was buried in Chicago at Oak Woods Cemetery, sharing the site with mayors of Chicago, governors of Illinois, and notable indviduals like Ida B. Wells and Enrico Fermi. Henry Chandler Cowles was buried at Oak Woods Cemetery in 1939; however, his remains were eventually moved to Kentucky.Henry B. and Indiana's Sand Dunes

Image caption: Henry Blake Fuller sits beneath a beach umbrella with pianist Winifred Middleton and poet/dancer Mark Turbyfill at the foot of "Top o' Dune" near Tamarack Station at Indiana Dunes (1920).

Source: Marie Kuda Archives, Oak Park, Illinois.

Henry had strong ties to Indiana Dunes; his social circles overlapped with many early park-supporters and he frequently visited for solace and inspiration. He was a "fixture at the Indiana Dunes summer home of University of Chicago friends." Henry often visited a place that he and his comrads called "Top o' Dune," where he spent countless hours enjoying the lake, the sands, and the living things that called it home.

In Bertram Cope's Year, Bertram is an English literature instructor at a ficticious Chicago university. Throughout the book, Bertram and others make multiple mentions of and excursions to the Indiana Dunes. In the book, Fuller writes:

Glimpses of Henry's life and time at the dunes can be gathered from a book of tributes collected and published by his "best friend," preeminent educator in drama, Anna Morgan. She wrote:“Mrs. Phillips had lately taken on a house among the sand dunes beyond the state line. This singular region had recently acquired so wide a reputation for utter neglect and desolation that—despite its distance from town, whether in miles or in hours—no one could quite afford to ignore it. Picnics, pageants, encampments and excursions all united in proclaiming its remoteness, its silence, its vacuity. Along the rim of ragged slopes which put a term to the hundreds of miles of water that spread from the north, people tramped, bathed, canoed, motored and week-ended. Within a few seasons Duneland had acquired as great a reputation for ‘prahlerische Dunkelheit’ [boastful darkness (German)]—for ostentatious obscurity—as ever was enjoyed even by Schiller’s Wallenstein. ‘Lovers of Nature’ and ‘Friends of the Landscape’ [early conservation group formed by Jens Jensen] moved through its distant and inaccessible purlieus in squads and cohorts. Everybody had to spend there at least one Sunday in the summer season. There were enthusiasts whose interest ran from March to November. There were fanatics who insisted on trips thitherward in January. And there were one or two super-fanatics—ranking ahead even the fisherman and the sand-diggers—who clung to that weird and changing region the whole year through.

Medora Phillips’ house was several miles beyond the worst of the hurly-burly. There were no tents in sight, even in August. Nor was the honk of the motor-horn heard even during the most tumultuous Sundays. The spot was harder to reach than most others along the twenty miles of nicked and ragged brim which helped enclose the wide blue area of the Big Water, but was better worth while when you got there. Her little tract lay beyond the more prosaic reaches that were furnished chiefly in the light green of deciduous trees; it was part of a long stretch thickly set for miles with dark and sombre green of pines. Our nature-lover had taken, the year before, a neglected and dilapidated old farmhouse and had made it into what her friends and habitués liked to call a bungalow. The house had been put up—in the rustic spirit which ignores all considerations of landscape and outlook—behind a well-treed dune which allowed but the merest glimpse of the lake; however, a walk of six or eight minutes led down to the beach, and in the late afternoon the sun came with grand effect across the gilded water and through the tall pine-trunks which bordered the zig-zag path. Medora had added a sleeping-porch, a dining-porch, and a lean-to for the car; and she entertained there through the summer lavishly, even if intermittently and casually.

‘No place in the world like it!’ she would declare enthusiastically to the yet inexperienced and therefore still unconverted. ‘The spring arrives weeks ahead of our spring in town, and the fall lingers on for weeks after. Come to our shore, where the fauna and flora of the whole country meet in one. All the wild birds pass in their migrations; and the flowers!’ Then she would expatiate on the trailing arbutus in April, and the vast sheets of pale blue lupines in early June, and the yellow, sunlike blossoms of the prickly-pear in July, and the red glories of painter’s brush and bittersweet and sumach in September. ‘No wonder,’ she would say, ‘that they have to distribute handbills on the excursion-trains asking people to leave the flowers alone!’”

In the book of tributes, a "Max von Luttichau" wrote:"Many in writing of him have alluded to his reticence and shyness, which were characteristic of him in a marked degree, but I never saw him with his friends when he was not the dominating figure, as he sat sipping a cup of tea while dispensing the most charming and witty conversation, and if he failed to appear when expected, which seldom happened, there was a disappointment, an immediate and keen sense of loss, so charming was his presence, and a general question arose, 'Where is Henry B. today?'"

Louise Van Hess Young wrote a tribute she entilted, "Henry Fuller and the Dunes":“It was always cheerfulness and kindliness that surrounded Henry B., and the keen interest he showed in everything made him the most delightful companion. He was a frequent visitor at my house at the Dunes. He loved the quiet and restfulness of the place.

I recall one day in late fall: Henry B. fixed a suet-box for the birds and stood by the hour watching his winged friends as they came and went. The expression on his face and the gleam in his eyes as he watched the birds is a memory very dear to me as an expression of his noble character.”

Mary Hastings Bradley included a poem she entlitled "HENRY BLAKE FULLER":“For fifteen years Henry B. Fuller was one of the closest of the Top o' Dune family. Even before, in the years of the garden activities in town, he was a part of everything — giving help in many ways — advising, encouraging and appreciating. I remember one day in spring — cold, rainy — a bit of snow now and then, just enough to make one remember and believe in warmer weather. I waited at the window to call him in to breakfast in the garden and to see my Darwin tulips which had opened in the night and made a sight for the gods. And who would see them first? Henry B. of course. So to the garden I led my friend under an umbrella; and there we sat under the mulberry tree, drinking our coffee and feasting upon Darwin tulips while the rain came down to give them a drink. I heard him excuse himself for this kindness in remarking later — that he took off his hat to such enthusiasm inspired by a backyard. And such was the beginning of my going to him with my joys and sorrows, always finding comfort and help.

The life at Top o' Dune was near his idea of how one should pass the time — a time for work, for rest, and for play — the best art, the best food and the best thoughts one could muster — for could we do less, with that beautiful blue, green, purple sea before us? Always singing and changing from hour to hour. And at night before the open fire — our long talks with the younger group — I recall his enjoyment of their ideas, and his haste to settle the world questions. A quiet voice from the big chair in the shadow of the fireplace would make this statement: "Nothing new under the sun, my boy, I went through this same talk in my youth, but you must go over the same field I suppose — one can't help much, it seems." We always had Lines Long and Short for breakfast, making him read aloud on the little hill where we took the breakfast tray.

Hours of talk followed in giving a sketch of the people who made up this remarkable book. After the reading we all went about our work, Henry B. seeing that this or that were mended — water — wood — down to the correction of a poem, advice on a first novel — questions answered and even listening to someone's first poem! He liked to call Top o' Dune a "going concern" and he liked being the most "going" of them all — which he was up to the very last. At luncheon we talked over the work done in the morning, and then Henry B. gave himself up to being a boy. For three hours no one knew where he went. The boys found him under a tree, his clothes still near the water — and then we found out he had "gone down to the sea again." He loved the sea, but not less the sand and the growing things upon the sands.

His love of the small animals was one of the dearest things about him. Many a time we talked of the actions of human beings, religion and the life to come. Always we ended nowhere, only once he said, "The older I grow I know less and less of what is best, wise and good. And so far as bad goes — I don't remember in my life any really bad person." We often talked of the spirit world. This, too, was a question, though it greatly interested him.

He loved Top o' Dune — "A house of dreams untold — to look out over the tree tops and face the setting sun." And here it was Henry B. found joy and rest and good cheer.

The Dunes can never be the same without him.”

"Elusive as the slipping ray of light

Upon an aspen leaf, he lived among us;

Sometimes a word escaping from his mild reticence

Twinkled its gleam and

Lit the vista of his polished mind,

And always after we looked for him

With eager wistfulness —

Not withdrawing, but withholding;

Not miserly but unprodigal of his own quality

He observed the human spectacle

With a gentle derision

That saw not much hope for it

And turned to the silver moonlight of the Dunes

As a better thing.

Always he flashed and withheld

Like a lighthouse revolving:

The Flash, and the absence.

A lighthouse throwing its fleet ironic ray

Upon the rocks and shallows of an existence

Which held no temptation to him but of laughter."

Social Circles and Literary Connections

H. B. Fuller was a social plus, a "witty raconteur." He entertained at the piano and was always welcome in stately homes. His friends described him as a gentleman of taste, cultivation, and great personal charm. Fuller was a resident of Hyde Park, in close proximatey to the 57th Street Artist Colony that attracted notables like Carl Sandburg, Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Harriet Monroe, and Sherwood Anderson. He attended lectures and lucheons at the University of Chicago, and was a frequent visitor to sculptor Lorado Taft's Midway Studios. Taft wrote in his tribute to Fuller:"What a boundless mental curiosity was his! How interested in all around him! Often this eagerness seemed paradoxical. With a mind so subtle and taste so marvelously attuned to the finest, he nevertheless was concerned in every step of Chicago's rowdy progress. He was literally a committee of the whole in his knowledge of our big town. He would travel impossible distances to see some new building or to note a civic improvement.

… But there was another more intimate phase of this remarkable awareness that I wish to refer to. It has been said that: 'The greatest thing that anyone can do for a fellow mortal is to show an interest in him.' This is where Mr. Fuller was supreme. Seldom did he talk of himself or of the details of his own work, but how inspiringly concerned he showed himself in the rest of us and in what we were trying to do. For many years he averaged one visit a week to the Midway Studios. He knocked at each door, knowing that he was welcome, and inspected our work with words of intelligent encouragement or, if pressed, of illuminative criticism, often of the greatest value. We came to look for these counsels and were ever grateful for them.”

Image caption: Inside view of Lorado Taft's Midway Studios. Taft is seated at the head of the table, with Henry Blake Fuller at his right. A plaster model of Taft's "Fountain of the Great Lakes" stands in the background.

Source: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-08076, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

H. B. Fuller was a preeminent member of the Little Room, an early twentieth century social club composed of artists, writers, and musicians. Included in this club was Jane Addams; Harriet Monroe; and Thomas Wood Stevens, author of the famous 1917 Dunes pageant, "Under Four Flags." Fuller was also a founding member of the Eagle’s Nest Art Colony in Oregon, Illinois with Lorado Taft. He volunteered at Jane Addams’ Hull House, sat on advisory board for Harriet Monroe’s Poetry magazine, wrote editorials for Chicago’s Record Herald, and helped establish the book review section of the Chicago Evening Post.

Henry B. was good friends with Elia and Robert Peattie, who lived near Lake Michigan on Chicago's south side. Robert wrote:

One of the Peattie's son, Donald, became one of the most-read nature writers of his era. Old copies of his work Flora of the Indiana Dunes (1930) can still found in regional antique shops and bookstores today. Donald and his wife Louise lived in the Indiana Dunes region and were members of Save the Dunes Council. They have the distinction to have originally encouraged Dorothy Buell to contact Senator Paul Douglas and ask for his support in establishing a National Park Service site at the Dunes. The Peattie's knew Paul Douglas through his wife, Emily née Taft—daughter of H. B.'s good friend, Lorado Taft."H. B. F. was so kind, so gentle a friend to all our household, that we seldom remembered that he was also a distinguished man of letters. He often was invited to our house, but was never more welcome than when he came on the moment's impulse, perhaps on some stormy, blowy day and slipped in to sit with us before the fire and drink a cup of tea. He had been down to watch old Michigan pounding on the shore; or had been looking at a new community playground ; or tramping about the steel mill district to see the foreign faces. If we had some notable joy, he called to congratulate us. When sorrow came he hastened to us. If we wrote a book he volunteered to correct the proof. We saw him at lectures and concerts, half-hiding in the background, and more interested in the reactions."

Closing Thoughts

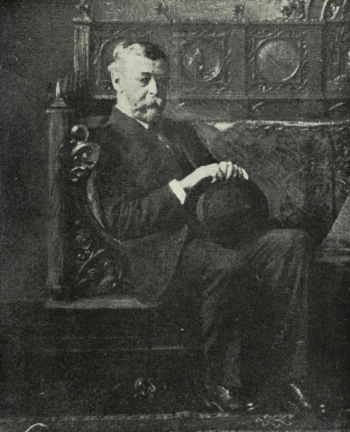

Image caption: Photograph of an older Henry Blake Fuller

Source: Tribute to Henry B. (1929) by Anna Morgan

Henry Blake Fuller's literary legacy is marked by his incisive social critques, pioneering exploration of homosexual themes, and a deep appreciation for natural beauty. Marie J. Kuda, a pioneering writer, archivist and publisher of LGB+ history, wrote of Fuller in Out and Proud in Chicago (2007):

Tributes to Fuller in Anna Morgan's book allude to his secretive nature. Author and friend Hamlin Garland wrote in his tribute:“The significance of noting Fuller’s sexual orientation lies in its effect on his work. The disapprobation of homosexuality led to self-censorship, coding, alternative expression, and sometimes self-destruction. There was a consensus among some who knew Fuller well, and among recent critics, that his seemingly natural reticence was exacerbated by his homosexuality.”

The most telling contribution came from Harriet Monroe of Poetry magazine:“Nothing escaped his notice. Strange little man! When we have all made report of him he will still remain a mystery, a lonely, wandering soul.”

Fuller's enduring contributions to American literature continue to resonate—reflecting a life dedicated to truth, art, and the unyielding pursuit of personal authenticity.“During this progress of a friendship both personal and professional one discovered gradually the unselfish sweetness of a spirit that could not, however endowed with a gift for beautiful utterance, reveal its true quality to the world. There was in its deepest recesses an unconquerable reticence — Henry Fuller found it impossible to tell his whole story. He could not give himself away, and therefore it may be that the greatest book of which his genius was capable was never written, the book which would have brought the world to his feet in complete accord and delight.”

Published Works

- The Chevalier of Pensieri-Vani (1890), a novel set in Italy

- The Chatelaine of La Trinité (1892), a novel set in the Alps

- The Cliff-Dwellers (1893), a novel set in Chicago

- With the Procession (1895), a novel set in Chicago

- The Puppet Booth (1896), twelve plays

- From the Other Side (1898), short stories set in Europe

- The Last Refuge (1900), a novel set in Italy

- Under the Skylights (1901), short stories set in Chicago

- Waldo Trench and Others (1908), short stories set in Italy

- Lines Long and Short (1917), a collection of free verse

- On the Stairs (1918), a novel set in Chicago

- Bertram Cope’s Year (1919), a novel set in Evanston

- Gardens of This World (1929), a novel set in Europe

- Not on the Screen (1930), a novel set in Chicago

Works Cited

- Bertram Cope's Year, Henry Blake Fuller, 1919.

- Tributes to Henry B., Anna Morgan, 1929

- Out and Proud in Chicago, Tracy Baim, 2007.

- The Chicago Author Who Wrote the First American Novel to Feature Gay Themes | WTTW Chicago

- HENRY BLAKE FULLER – Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame

- Henry Blake Fuller – Chicago Literary Archive

- Henry Blake Fuller: Chicago Literary Hall of Fame Winner (chicagoliteraryhof.org)