Last updated: October 19, 2023

Person

Edwin Way Teale

Edwin Way Teale Papers, University of Connecticut

American naturalists have been cited for combining philosophy and writing in ways that have affected how concerned citizens value and care for their environment. Edwin Way Teale has been called one of the twentieth century’s most influential naturalists because of his ability to combine the artistic, philosophical, and scientific in his writing.

According to the extensive Biographical Dictionary of American and Canadian Naturalists and Environmentalists, “Through his popular books [Teale] convinced Americans they had a personal stake in the preservation of ecological zones [and] convinced them to support national parks and conservation movements.” Teale credited his renowned career to his rich childhood spent in the Indiana Dunes, where he developed a love for nature, an eye for photography, and an accessible writing style. He immortalized his boyhood adventures in Dune Boy and later works, including Wandering through Winter, for which he became the first naturalist to win a Pulitzer Prize. Teale is included in the “heyday of dunes art and literature begun and perpetuated” by a group of artists of the “Chicago Renaissance” movement. Naturalists, conservationists, writers, and reviewers have ranked him among the renowned American naturalists who preceded him, including John Muir, John Burroughs, and Henry David Thoreau.

Born Edwin Alfred Teale on June 2, 1899 in Joliet, Illinois, he later wrote that he rejected the dismal industrial landscape of his parents’ home. Instead Teale favored the holidays and summers he spent with “Gram and Gramp” exploring their Lone Oak farm in the Indiana Dunes. In Dune Boy (1943), Teale wrote that “to a boy alive to the natural harvest of birds and animals and insects, [Lone Oak] offered boundless returns.” In The Lost Woods (1945), Teale recalled a sleigh ride through a nearby forest at the age of six with his grandfather; he points to this event as “the starting point of my absorption into the world of nature.” As he grew up, Teale’s interest in nature grew as well. At the age of seven or eight Teale looked through his first microscope, and at nine he declared himself a naturalist. By the age of ten he finished his twenty-five chapter “Tails [sic] of Lone Oak,” and at twelve he changed his name to “the more distinguished” Edwin Way Teale.

Throughout his career in interviews and in books, Teale recalled stories about the character-forming adventures he had in the Indiana Dunes. He often recited a story about taking imaginary photographs with an out-of-order camera at the age of eight until a few years later when he was able to buy his first box camera. The young Teale had figured out that at his grandfather’s pay rate of a cent and a half for every quart of strawberries he picked, he would have to pick 20,000 strawberries to get a box camera, film, developing kit and printing material from the Sears Roebuck catalogue. Later in his career he reflected on this influential purchase: “it was the black box of Lone Oak – the camera that 20,000 strawberries purchased – that opened the door to all this later pleasure.” However, according to Teale, the “Lone Oak days came to their end almost at the same time that the golden age of boyhood drew to a close.” In January 1915, his grandparents’ farm burned to the ground.

In 1918, Teale enrolled at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana; he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English literature in 1922. After graduation he took a job as head of the Department of Public Speaking at Friends University in Wichita, Kansas. After his first year, he returned to Indiana to have “exercise and adventure,” traveling 100 miles by rowboat with a college friend and another 300 miles by himself. On August 1, 1923, Teale married his college sweetheart Nellie Imogene Donovan, who would become his “partner naturalist.” The newlyweds returned to Friends University for another school year; Edwin continued to teach public speaking, and Nellie worked as the athletic director.

The Teales moved to New York City in 1924; Edwin attended Columbia University, and worked to further his writing career. After a period of rejection, he obtained regular work assisting Frank Crane, a popular religious writer, with his daily editorial column. The Teales’ only child, David, was born in 1925. In 1926, Teale received his M.A. from Columbia in English literature. In July of that year, he also took possession of his grandparents’ property in the Indiana Dunes. The Teales built a brick cottage there and maintained the property until selling it in 1937.

Caption: Edwin helps his son David build a model airplane in 1935. Photograph from Edwin Way Teale Papers, University of Connecticut.

In 1928 Popular Science hired Teale as a staff writer, even though he reportedly left his only letter of recommendation at home in the pocket of a different suit. He worked for the magazine for thirteen years and “liked the work because it was active and varied.” He spent his time at Popular Science perfecting his photography skills with help from a staff photographer and began contributing photos to the magazine. Teale applied these skills to pioneering a technique for photographing insects that would launch his career. Teale used an icebox to immobilize his insect subjects, then placed them in a natural surrounding, set up a camera with magnifying lens, and waited for the subject to reanimate. In this manner, he represented the world of insects in a way people had never seen before – up close and larger than life. He began “bashfully” exhibiting his photos around New York City. These photos were picked up by nature magazines and eventually compiled for his first critically acclaimed book, Grassroot Jungles, a collection of over one hundred insect photos. Published in 1937 by Dodd, Mead & Company, Grassroots Jungles became the first of many of Teale’s works to be released by the publisher. Edward H. Dodd, head of this publishing house, also wrote the most detailed biography of the naturalist, Of Nature Time and Teale.

In January 1941, Teale’s The Golden Throng was published, receiving praise for the photographs of bees. On October 15 of that year, Teale left his job at Popular Science to become a freelance writer and photographer. He called that day his “own personal Independence Day.” Although he was worried about the “irresponsibility” of leaving a steady job with a son in high school and an invalid mother in his care, within weeks his magazine writing and photographs were earning more than his former salary.

Teale’s decision to undertake freelance writing and photography also gave him time to work in his insect garden, which would further influence his career path. For several years, Teale paid ten dollars a year for “insect rights” for a plot of land near his Long Island home. He planted “sunflowers, hollyhocks, spice bush and milkweed,” as well as “troughs offering honey and syrup to bees and butterflies (and) hidden pie pans with putrid meat to attract carrion beetles” to his garden. Teale’s biographer and publisher, Edward H. Dodd, wrote that “this small plot of land, undesirable for real-estate purposes, even in Long Island became his outdoor laboratory, his photography studio, his wilderness to explore.”

In October 1942, Dodd, Mead & Company published the result of these photography experiments, Near Horizons: The Story of an Insect Garden. Prominent publications praised the book, including the New York Times, Scientific Monthly, and The Scientific American, which proclaimed Teale one of few scientists “heavily gifted with literary charm.” In relation to this latest book, Teale described himself as “an explorer who stayed at home, a traveler in little realms, a voyager within the near horizons of a hillside.” In April 1943, the John Burroughs Association awarded Teale the John Burroughs Medal for Near Horizons as “a distinguished book of natural history."

In October 1943, Teale published Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist. In this work, Teale recollected the years he spent among the natural wonders of the Indiana Dunes, surveying his surroundings from the roof of the farm house, the shores of Lake Michigan, and the floor of the surrounding woods. He helped his grandparents with chores, made notes on the creatures he saw, created a natural history museum in the barn, attempted to build an airplane, began to write nature stories, and take his first photographs. He credits his grandparents for giving him freedom to explore and develop his interest in nature. “At Lone Oak there was room to explore and time for adventure. A new world opened up around me. During my formative years, from earliest childhood to the age of fifteen, I spent my most memorable months here, on the borderland of the dunes.” Dune Boy received a long and glowing review in the New York Times. The reviewer alluded to the book and Teale's childhood, as representative of something inherently American. The reviewer stated that “Dune Boy is not only the record of a naturalist's beginnings but one of our many-sided American way of life.”

Caption: Edwin stands beside his son David, 1944 . Photograph from Edwin Way Teale Papers, University of Connecticut.

Indicative of the book’s popularity, the army distributed more than 100,000 copies of Dune Boy during World War II. Teale commented that “he heard from many who had read it while engaged in battle for freedom in all parts of the world” and some scholars have suggested that the book presents “a timeless model of the democratic common life, for many . . . an image of their real American homeland.” The Teales’ son, David, served as part of an assault team under General George Patton during the war. After a period of considering him missing in action, in March 1945 the Teales’ received word that their nineteen-year-old son had been killed. The Teales claimed that only their love of nature got them through this difficult time.

Despite the tragedy, Teale’s career flourished. On November 19, 1945, The Lost Woods: Adventures of a Naturalist was published with critical acclaim. Beginning in January 1946, newspapers across the country began running Teale’s Nature in Action column. The Indianapolis Star began running the column on January 14, 1946. In November 1946, Dodd, Mead & Company released a version of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, “lovingly prepared” by Teale, who wrote an introduction and interpretive comments, and provided 142 of his own photographs. In March 1947, the Teales began the first of several trips that would become the series, The American Seasons.

On June 14, 1948, Teale delivered the commencement address at his alma mater Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. A few months later, in September 1948, Dodd, Mead & Company published Days Without Time, which received mixed reviews. In August 1949, Teale released The Insect World of J. Henri Fabre, a selection of writings by the French entomologist, for which Teale provided a “charming and sympathetic” introduction and interpretive comments. The American Museum of Natural History hosted Insect World from November 1949 to January 3, 1950; this exhibit featured Teale’s enlarged insect photographs.

Caption: Edwin and Nellie Teale, 1948. Photograph from Edwin Way Teale Papers, University of Connecticut.

In November 1951, Dodd, Mead & Company released North with the Spring, the account of the Teales’ 17,000-mile, four month long pursuit of spring across America. According to one New York Times reviewer, the book was “packed with solid learning” about the plants, animals, and weather they encountered, but it was also a “warm and moving” story of husband and wife naturalists. Contemporary environmentalists such as Rachel Carson embraced North with the Spring. Years later, the New York Times printed a list of books which “might be admired twenty-five years hence,” which included North with the Spring and “Teale's other nature books, all of them combinations of sound scientific observation, graceful writing and contagious enthusiasm.”

On December 16, 1951, the New York Times ran the first of many nature articles and book reviews that Teale contributed to this highly respected paper. In his first article, Teale wrote about the city's wildlife and the efforts needed to protect the areas in which that wildlife abounded. He lamented the increasing urbanization and encroaching suburbs. Teale also wrote about the importance of contact with nature “to restore mental tone and health,” a common concern among conservationists during this time period.

Over the next few years, Teale produced compilations of selected nature writing, including Green Treasury: A Journey through the World’s Great Nature Writing (1952) and The Wilderness World of John Muir (1954), which made the New York Times “outstanding books of the year” list. Reviewers called Teale “one of our most sensitive and observant naturalists” and among the “best of Americans writing about nature,” comparing him to Thoreau and Burroughs. In November 1953, he published Circle of Seasons: The Journal of a Naturalist’s Year. Teale attended conservation fundraisers and entomological meetings. As his popularity grew, his earlier books were reprinted and adapted into children’s versions.

In August 1956, Teale published Autumn Across America, the second book in the American Seasons series. This time, the Teales followed fall through twenty-six states from Cape Cod to California over three months. Autumn Across America received even greater acclaim than North with the Spring. It was presented to the White House Library and described as a “revelation of the seasonal wonders that lie around us and the reflections they caused in the searching mind and genial soul of the author.”

In 1957, Dune Boy was reissued, and Teale received an honorary doctorate of letters from Earlham College. In 1958, Teale became president of the Thoreau Society and continued to have articles printed in the New York Times. In 1959, the Teales left their Long Island home because of increased population and suburbanization and moved to a 130-acre estate in Hampton, Connecticut, which they named Trail Wood.

In 1960, Teale revisited the Indiana Dunes during a road trip that would become the third installment of The American Seasons. In October 1960, Teale published Journey into Summer. The New York Times noted that “in these pages the Great Lakes come alive.” Indiana newspapers highlighted the chapter, “River of Fireflies,” about the author’s experiences on the Kankakee River located in northwestern Indiana. Journey into Summer was praised not just as an informative record of a 19,000-mile journey and seasonal study, but as “a unique portrait of a nation,” putting Teale “in a class with John Bartram and James Audubon.” Indiana University presented Teale with the Indiana Author’s Day Award in 1961 for Journey into Summer.

Over the next several years, Teale continued to write books and articles and make contributions to the works of other naturalists. His major publications included; The Lost Dog (1961), The Strange Lives of Familiar Insects (1962), The Thoughts of Thoreau (1962), and Audubon’s Wildlife (1964).

In fall 1965, Teale published Wandering through Winter, the most celebrated of all his works. The Teales began their road trip in the southwestern United States near San Diego and greeted the last day of winter in the northern part of Maine. Teale covered a wide range of topics from beetles to whales to sunsets. The New York Times ran a laudatory review of Wandering through Winter, praising Teale's work as without fault and his writing as combining the best of Thoreau, Hudson, and Muir. The reviewer credited Teale with saving nature writing. Indianapolis newspapers called Teale a “Hoosier author-naturalist” and discussed the chapter on his adventure in an Indiana ice storm.

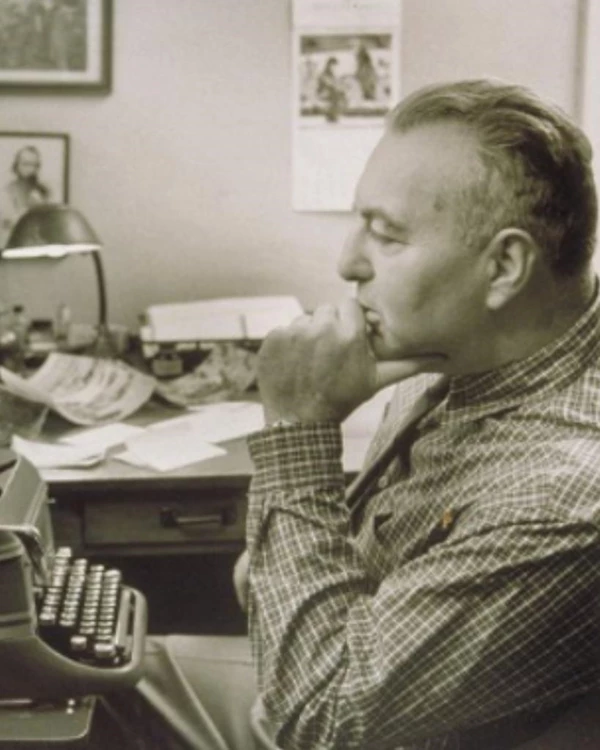

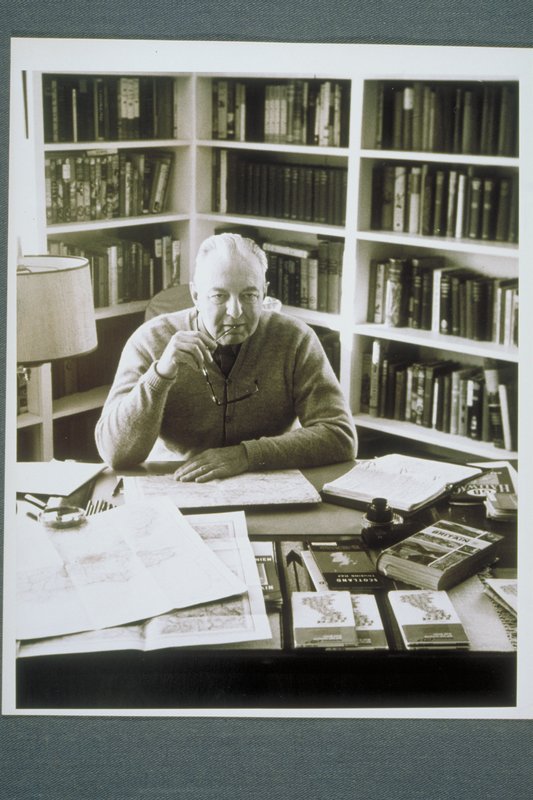

Caption: Edwin sits at his desk in 1970. Photograph from Edwin Way Teale Papers, University of Connecticut.

In May 1966, Teale became the first naturalist to win a Pulitzer Prize (for general nonfiction) for Wandering through Winter. Although he continued to contribute introductions and chapters to colleagues’ books, and have his own books reprinted and adapted as children’s stories, his publishing slowed somewhat over the next decade. On October 10, 1970, Indiana University presented Teale with an honorary degree. During that same month, the author published Springtime in Britain, an account of the Teales’ rigorous trip through a cold and damp English spring. Teale collected and published his best photographs in Photographs of American Nature, released on November 24, 1972. In 1974, Teale published the story of his move to Trail Wood as A Naturalist Buys an Old Farm. In 1978, Teale produced his last work, A Walk through the Year. The book summarized a year with his wife Nellie at Trail Wood, highlighting the memorable experiences they shared.

On October 18, 1980, Teale died at the age of 81. On May 17, 1981, the Connecticut Audubon Society dedicated Trail Wood as the Edwin Way Teale Memorial Sanctuary, and it became steward of the property. Nellie remained at the farm until her death in 1993. In 1998, the University of Connecticut initiated the Edwin Way Teale Lecture Series. Visitors come to hike the grounds to see Teale’s landscape of “woods, open fields, swamps, two good-sized brooks and a waterfall.” Teale’s works continue to be reprinted, including a reissue of Dune Boy in 2002.