Last updated: October 19, 2023

Article

Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist

Joseph Gruzalski

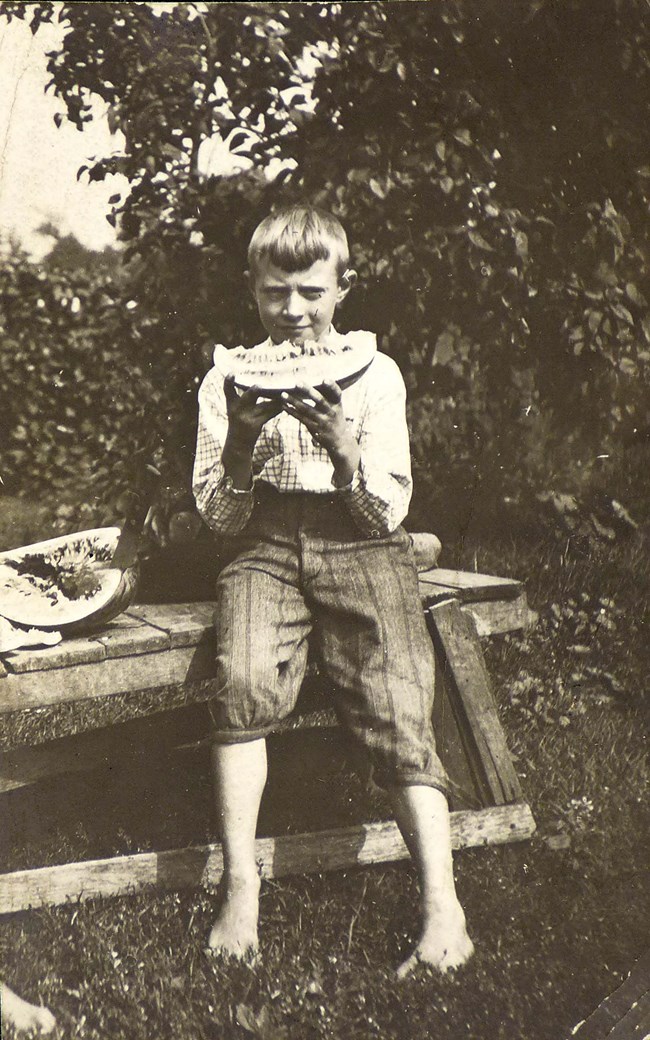

"Dune Boy" is a beloved memoir by Edwin Way Teale that synthesizes tales from his early life and experiences with nature. Though Edwin and his parents lived in Joliet, an Illinois city, he spent his summers with "Gram and Gramps" on their farm in Furnessville, Indiana. His turn-of-the-century adventures are both nostaglic and heartwarming. The book provides insights into his formative years and his passion for the natural world. Over 100,000 copies were issued to servicemen in World War II.

The following excerpt is from a chapter called "The Death of a Tree." It chronicles how the namesake tree of his grandparents' "Lone Oak" farm slowly succumbed. Even in its death, there was new life.

The Death of a Tree

"For a great tree death comes as a gradual transformation. Its vitality ebbs slowly. Even when life has abandoned it entirely it remains a majestic thing. On some hilltop a dead tree may dominate the landscape for miles around. Alone among living things it retains its character and dignity after death. Plants wither; animals disintegrate. But a dead tree may be as arresting, as filled with personality, in death as it is in life. Even in its final moments, when the massive trunk lies prone and it has moldered in a ride covered with mosses and fungi, it arrives at a fitting and a noble end. It enriches and refreshes the earth. And later, as part of other green and growing things, it rises again.

The death of the great white oak which gave our Indiana homestead its name and which played such an important part in our daily lives was so gentle a transition that we never knew just when it ceased to be a living organism.

It had stood there, toward the sunset from the farmhouse, rooted in that same spot for 200 years or more. How many generations of red squirrels had rattled up and down its gray-black bark! How many generations of robins had sung from its upper branches! How many humans, from how many lands, had paused beneath its shade!

The passing of this venerable giant made a profound impression upon my young mind. Just what caused its death was then a mystery. Looking back, I believe the deep drainage ditches, which had been cut through the dune-country marshes a few years before, had lowered the water-table just sufficiently to affect the roots of the old oak. Millions of delicate root-tips were injured. As they began to wither, the whole vast underground system of nourishment broke down and the tree was no longer able to send sap to the upper branches.

Like a river flowing into the desert, the life stream of the tree dwindled and disappeared before it reached the topmost twigs. They died first. The lead at the tip of each twig, the last to unfold, was the first to wither and fall. Then, little by little, the twig itself became dead and dry. This process of dissolution, in the manner of a movie run backward, reversed the development of growth. Just as, cell by cell, the twig had grown outward toward the tip, so now death spread, cell by cell, backward from the tip.

Sadly we watched the blight work from twig to branch, from smaller branch to larger branch, until the whole top of the tree was dead and bare. For years those dry, barkless upper branches remained intact. Their wood became gray and polished by the winds. When thunderstorms rolled over the farm from the northwest the dead branches shone like silver against the black and swollen sky. Robins and veeries sang from these lofty perches, gilded by the sunset long after the purple of advancing dusk filled the spaces below.

Then, one by one, their resiliency gone, the topmost limbs crashed to earth, carried away by the fury of storm-winds. In fragments and patches, bark from the upper trunk littered the ground below. The protecting skin of the tree was broken. In through the gaps poured a host of microscopic enemies, the organisms of decay.

Edwin Way Teale Papers, University of Connecticut

Ghostly white fungus penetrated into the sap-wood. It worked its way downward along the unused tubes, those vertical channels through which had flowed the life-blood of the oak. The continued flow of this sap might have kept out the fungus. But sap rises only to branches clothed with leaves. As each limb became blighted and leafless, the sap-level dropped to the next living branch below. And close on the heels of this descending fluid followed the fungus. From branch to branch its silent, deadly descent continued.

Soft and flabby, so unsubstantial it can be crushed without apparent pressure between a thumb and forefinger, this pale fungus is yet able to penetrate through the hardest of woods. This amazing and paradoxical feat is accomplished by means of digestive enzymes which the fungus secretes and which dissolve the wood as strong acids might do. These fungus-enzymes, science has learned, are virtually the same produced by the single-celled protozoa which live in the bodies of the termites and enable those insects to digest the cellulose in wood.

Advancing in the form of thin white threads, which branch again and again, the fungus works it way from side to side as well as downward through the trunk of a dying tree. Beyond the reach of our eyes the fungus kept spreading within the body of the old oak, branching into a kind of vast, interlocking root-system of its own, pale and ghostly.

Behind the fungus, along the dead upper trunk, yellow-hammers drummed on the dry wood. I saw them, with their chisel-bills, hewing out nesting holes which, in turn, admitted new organisms of decay. In effect, the dissolution of a great tree is like the slow turning of an immense wheel of life. Each stage of its decline brings a whole new, interdependent population of dwellers and their parasites.

Even when the lower branches of the oak were still green, insect wreckers were already at work above them. First to arrive were the bark beetles. In the earliest stages their fare was the tender inner layers of the bark, the living bond between the trunk and its covering. As death spread downward in the oak, as freezing and storms loosened the bark, the beetles descended, foot by foot. Some of them left behind elaborate patterns, branching mazes of tunnels that took the appearance of fantastic “thousand-leggers” engraved on wood.

Edwin Way Teale Papers, University of Connecticut

During the winter when I was twelve years old a gale of abnormal force swept the Great Lakes region. Gusts reached almost hurricane proportions. Weakened by the work of the fungus, bacteria, woodpeckers, and beetles, the whole top of the tree snapped off some seventy feet from the ground. After that the progress of its dissolution was rapid.

Finally the last of the lower leaves disappeared. The green bade of life returned no more. On summer days the sound of wind sweeping through the old oak had a winter shrillness. No more was there the rustling of a multitude of leaves above our hammock; no more was there the “plump!” of falling acorns. Leaves and acorns, life and progress, were at an end.

In the days that followed, as the bark loosened to the base, the wheel of life, which had its hub in the now-dead oak, grew larger.

I saw carpenter ants hurrying this way and that over the lower tree-trunk. Ichneumon flies, trailing deadly, drill-like ovipositors, hovered above the bark in search of buried larvae on which to lay their eggs. Carpenter bees, their black abdomens glistening like patent leather, bit their way into the dry wood of the dead branches. Click beetles and sow-bugs and small spiders found security beneath fragments of the loosened bark. And around the base of the tree swift-legged carabid beetles hunted their insect prey under the cover of darkness.

Yellowish brown, the wood-flour of the powder-post beetles began to sift about the foot of the oak. It, in turn, attracted the larvae of the Darkling beetles. Thus, link by link, the chain of life expanded. To the expert eye the condition of the wood, the bark, the ground about the base of the oak—all told of the action of the inter-related forms of life attracted by the death and decay of a tree.

Below all this activity, beyond the power of human sight to detect, other changes were taking place. The underground root system, comprising almost as much wood as was visible in the tree rising above-ground, was also altering.

Fungus, entering the damaged root-tips or working downward from the infected trunk, followed the sap channels and hastened decay. The great main roots, spreading out as far as the widest branches of the tree itself, altered rapidly. Their fibers grew brittle; their old pliancy disappeared; their bark split and loosened. The breakdown of the upper tree found its counterpart, within the darkness of the earth, in the dissolution of the lower roots.

Edwin Way Teale Papers, University of Connecticut

I remember well the day the great oak came down. I was fourteen at the time. Gramp had measured distances and planned his cutting operations in advance. He chopped away for fully half an hour before he had a V-shaped bite cut exactly in position to bring the trunk crashing in the place desired. Hours filled with the whine of the cross-cut saw followed.

Then came the great moment. A few last, quick strokes. A slow, deliberate swaying. The crack of parting fibers. Then a long “sw-o-sh!” that rose in pitch as the towering trunk arced downward at increasing speed. There followed a vast tumult of crashing, crackling sound; the dance of splintered branches; a haze of dead, swirling grass. Then a slow settling of small objects and silence. All was over. Lone oak was gone.

Gram, I remember, brushed away what she remarked was dust in her eyes with a corner of her apron and went inside. She had known and loved that one great tree since she had come to the farm as a bride of sixteen. She had seen it under all conditions and through eyes colored by many moods. Her children had grown up under its shadow and I, a grandchild, had known its shade. Its passing was like the passing of an old, old friend. For all of us there seemed an empty space in our sky in the days that followed.

Gramp and I set to work, attacking the fallen giant. Great piles of cordwood, mounds of broken branches for kindling, grew around the prostrate trunk as the weeks went by. Eventually only the huge, circular table of the low stump remained—reddish brown and slowly dissolving into dust.

For two winters wood from the old oak fed the kitchen range and the dining-room stove. It had a clean, well-seasoned smell. And it burned with a clear and leaping flame, continuing—unlike the quickly consumed poplar and elm—for an admirable length of time. Like the old tree itself, the fibers of these sticks had character and endurance to the very end."