Last updated: February 26, 2025

Person

Cuff Whittemore (Cartwright/De Carteret)

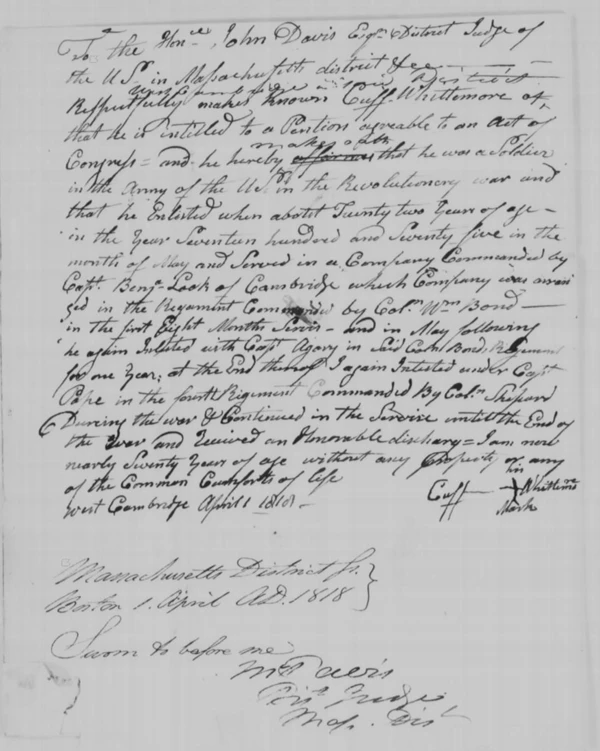

Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, NARA M804, via Fold3.com

A minute man in the Menotomy Minute Company, Cuff Whittemore fought in both the Battle of Lexington and Concord and the Battle of Bunker Hill. He continued his military service in the Continental Army through 1782, participating in the Battle of Saratoga.

Born of African and possibly Native American heritage, there is no indication that Whittemore was enslaved. Rather, he can be termed "unfree:" not "owned" by an enslaver, but nevertheless dependent on the White families he lived with.1 Legally, he was a freeman, but his social status and his non-White heritage were great disadvantages. Joining the local militia – indeed a prestigious Minute Company! – supported Whittemore’s social status as a truly free man.

Cuff Whittemore grew up in the Menotomy neighborhood, which today is composed of West Arlington, East Cambridge, and a snip of Medford. In the 1700s, Menotomy lay on the borders of Cambridge and Charlestown. Whittemore’s mother was Margaret De Carteret, her last name indicating which household she lived in. In all probability, Margaret passed on to him Native American heritage.2 His father's identity is unknown but Cuff's first name is an English version of the Ghanian "Kofi," meaning "born on Friday." This suggests his father was West African. Throughout Cuff Whittemore’s lifetime, historical records identified him as "negro" or "Black."3

In 1770, at the age when young men entered apprenticeships, he left the De Carteret household and entered into the Menotomy home of William Whittemore, a schoolteacher and Harvard graduate. He chose to transfer his loyalty to the very prominent Whittemore family and changed his last name from De Carteret to Whittemore. This transfer was parallel to that of Abigail De Carteret, a young woman from the household he grew up in who had married William Whittemore, and whom he accompanied into the new household.4

As the tension between local residents and British government representatives grew into military confrontation, Whittemore enlisted in the new local militia company, the Menotomy Minute Men. He was sworn into this minute man company on April 6, 1775, an action only possible for a freeman. Massachusetts communities instituted Minute companies starting in September 1774. Members were selected based on their willingness, strength, speed, and skill. They were highly trained and, unlike militia companies, paid for their time.5 Membership was a good choice for a person who wanted income and had the ability to make the muster.

The Menotomy Minute Men records show three other non-White members of this company of 50 men. These four men made up 8% of the Menotomy Minute Men, two of them being from far-away Stoneham. At this time, Massachusetts units were almost always composed of men of a single community. In comparison, the 1754 Massachusetts slavery census recorded 11 non-White enslaved women and men – that number amounted to 5% of the Menotomy population.6 The Menotomy Minute Man unit had a very high percentage of non-White infantry men, indicating that, in 1775, young men of African and Native heritage were gladly included in local military strength.

Whittemore's unit took part in the Menotomy skirmish of the Battle of Lexington and Concord.7 They also participated in the Battle of Bunker Hill, where the unit was posted in the redoubt. Historian Samuel Swett wrote about Whittemore’s actions during the battle:

Cuffee Whittemore fought bravely in the redoubt. He had a ball through his hat on Bunker Hill, fought to the last, and when compelled to retreat, though wounded, the splendid arms of the British officers were prizes too tempting for him to come off empty handed, he seized the sword of one of them slain in the redoubt, and came off with the trophy, which in a few days he unromantically sold.8

Whittemore continued to serve in his unit after Bunker Hill. In 1777, Whittemore was captured at Saratoga and assigned to a British field officer, possibly General John Burgoyne, as a personal servant. When Burgoyne’s troops were in crisis and trapped along the Saratoga River, Whittemore jumped the officer's horse and galloped across the river while British soldiers bombarded him with musket fire.9

The fact that tales of Cuff Whittemore’s Battle of Saratoga exploits were part of Menotomy's 1800s collective narrative indicates that he returned home to tell the tales himself. Bounded by his "unfreedom," he had limited options to choose from in Menotomy. He chose to live independently, without a permanent roof over his head: "He used to work by the day among the farmers, slept in barns and lived almost anyhow."10 To be autonomous and independent were his choices over his other option, dependency in a Menotomy household. He never married or had any (known) children but nevertheless was a recognized member of the community.

Whittemore stated in his 1818 veteran's pension application that "I am now nearly seventy years of age without any property or any of the Common Comforts of life." Two years later, the required second application for a pension, now stating Whittemore’s age as seventy-five, was accompanied by a testimony from his very first Lieutenant, Solomon Bowman. Bowman served as an eyewitness to the length and the quality of Whittemore’s service in both militia and new national army.11

Whittemore’s pension request was accepted. As a non-officer veteran, he received $8 per month, as did all others of this status.12 He had been able to retain community ties and respect, despite the hardships that defined the last phase of his life. Cuff Whittemore died on January 26, 1826 in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

Footnotes:

- Jared Hardesty has written a probing work that explores the term “unfreedom” (Jared Hardesty, Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston (New York: NYU Press, 2016).

- That Whittemore was not enslaved is indicated by a legal document. His mother was termed a “mulatto” (at that time used for people with Native American heritage), granted property, and assured that her children would not be enslaved in the 1709 will of Elizabeth Dunster Wade Thomas, a woman upon whose household Margaret was dependent. See text of this will in Samuel Dunster. Henry Dunster and His Descendants. (Central Falls, RI: E.L. Freeman & Co., 1876), p. 33.

- Nineteenth-century Arlington historical tradition designates him “a slave.” However, the only legal documentation made during his lifetime are his military records, where he is “reported a negro” and “reported a baker.” His military pension applications of 1818 and 1820 do not give any indication of former enslavement. His own testimony speaks “only” of no longer being able to earn a living.

- Samuel Dunster, Henry Dunster and His Descendants (Central Falls, R.I.: E.L. Freeman & Co., 1876), https://archive.org/details/henrydunsterhisd00duns (accessed 09/19/2021), p. 61.

- See John R. Galvin, The Minute Men: The First Fight: Myths and Realities of the American Revolution (Potomac Books, Incorporated, 1989).

- Benjamin Cutter, William R. Cutter, History of the town of Arlington, Massachusetts, formerly the second precinct in Cambridge, or District of Menotomy, afterward the town of West Cambridge. 1635-1879 with a genealogical register of the inhabitants of the precinct (Boston 1880), p. 57, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:2001.05.0320, accessed 9/19.2021.

- Menotomy was the most intense, prolonged, and bloody phase of the April 19th battle in what is now the center of Arlington. 779 local men joined the battle at Menotomy, representing 37 militia and minute companies from 11 communities (Cutter & Cutter, History of the town of Arlington, Massachusetts, p. 49).

- Samuel Swett, Notes to his sketch of Bunker-hill battle (Boston 1825), pp. 25-26.

- This anecdote seems to originate in Whittmore’s own storytelling. There are two versions published by Arlington historians (J.B. Russell cited in Cutter & Cutter, History of the town of Arlington, Massachusetts, p. 204; Charles S. Parker, Town of Arlington: Past and Present; A Narrative of Larger Events and Important Changes in the Village Precinct and Town from 1637 to 1907 (Arlington: C.S. Parker & Son, 1907), citing Col. Thompson).

- J.B. Russell cited in Cutter & Cutter, History of the town of Arlington, Massachusetts, p. 202.

- Whittemore, Cuff, Pension No. S. 33896, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, via Fold3.com.

- Will Graves, “Pension Acts: An Overview of Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Legislation and the Southern Campaigns Pension Transcription Project” (revised March 28, 2017) http://revwarapps.org/revwar-pension-acts.htm#:~:text=On%20March%2018%2C%201818%2C%20Congress%20enacted%20legislation%20which,for%20non-officers.%20So%20many%20applications%20were%20filed%20under

The following is from the 2004 National Park Service study Patriots of Color researched and prepared by George Quintal:

Cuff Whittemore was born circa 1751.I Before the Revolution, he was called Cuff Cartwright (or De Carteret) and was the servant of William Whittemore.II ‘He used to work by day among the farmers, slept in barns and lived almost anyhow.’III

A local history describes his activity on 19 April 1775:

Cuff was on the hill with the Menotomy militia [under Capt. Benjamin Locke], of which Solomon Bowman was lieutenant, and on the opening of the fight at that point, which was evidently near the house of Jason Russell at Arlington, the negro acted cowardly, and in his alarm turned to run down the hill. But the lieutenant threatened to shoot him with a horse pistol, and pricked him in the leg with the point of his sword. This brought Cuff to his senses and the negro “about facing” fought through the contest, as the colonel [Col. Ebenezer Thompson, the narrator] said, like a wounded elephant, making two “cuss’d Britishers” bite the dust.IV

He then enlisted in the eight month’s service from Cambridge on 4 June 1775 in Capt. Benjamin Locke’s company, in Col. Thomas Gardner’s regiment. This company served in the Battle of Bunker Hill, where his Colonel was mortally wounded and Lt. Col. William Bond took over command. It is stated that Cuff:

… fought bravely in the redoubt. He had a ball through his hat on Bunker Hill, fought to the last, and when compelled to retreat, though wounded, the splendid arms of the British officers were prizes too tempting for him to come off empty handed, he seized the sword of one of them slain in the redoubt, and came off with the trophy, which in a few days he unromantically sold. He served faithfully through the war, with many hair-breadth ‘scapes from sword and pestilence.’V

An October 1775 descriptive roll at Prospect Hill describes him as a ‘negro’ and as follows:VI

age: 24

stature: 5 ft. 10 ½ in.

His former master, William Whittemore, interceded for him in a request for wages in October 1775. On 1 December 1775, he was listed on an ‘order for bounty coat dated Prospect Hill.’VII

In 1776, he served for one year in Capt. Daniel Egery’s company, in Col. William Bond’s regiment.VIII This unit served at Ticonderoga at the time the American Fleet under Gen. Benedict Arnold was defeated.

By 15 May 1777, he was living in Dartmouth (MA) and had enlisted in the Continental Army for three years under Capt. Isaac Pope, in Col. William Shepard's regiment.IX This unit fought at Saratoga where Cuff Whittemore was taken prisoner and ‘ordered to take care of [Gen. Burgoyne’s] charger for a few moments [when] he mounted him and returned to the American Camp.’X A local history gives further details:

… just before the capture of [Burgoyne] at Saratoga, he was ordered to take the General’s favorite horse one morning to the brook to water. The American and British armies lay on each side of it, half a mile or so apart. After the horse had drank sufficiently, Cuff concluded to join the Americans, and dashing through the brook, while the British bullets flew thick at him, reached our lines.XI

On 1 April 1818 he applied for a U.S. pension, which was granted.XII In June 1820 he had to reapply in order to prove his need. He described himself as a ‘pauper’ in Charlestown, ‘without any estate,’ and ‘very infirm and has no family and is unable to support himself.’XIII

Cuff Whittemore died in Charlestown (MA) on 26 January 1826.XIV He is one of a very few men of color who was honored with an obituary notice.XV

Footnotes:

I. Birth date backwardly-computed, based on age in military descriptive roll; in his 1818 pension application (see United States Revolutionary War Pensions footnote), he gives his own age as ‘about 22’ in 1775 [bca, 1748], per Frame 225. In his 1820 pension application, he gives his age as 75 [bca. 1750] per Frame 229. In his obituary, his age is given as 80 in 1826 [bca. 1756] (see obituary footnote). With all of this conflicting data, a birth year of 1751 seemed like a good compromise date.

II. Parker, Charles S. Town of Arlington [MA] Past and Present … (1901), 197 states: ‘Master William Whittemore, a graduate of Harvard College and a local school teacher … had married a member of the Carteret family.’

III. Cutter, Benjamin and William R. History of the Town of Arlington, Massachusetts formerly the Second Precinct in Cambridge or District of Menotomy, afterward the Town of West Cambridge 1635-1879 … (1880), 202.

IV. Parker, Charles S. Town of Arlington [MA] Past and Present … (1901), 197; as an old man, Bowman provided an affidavit for Cuff in his application for a pension (see United States Revolutionary War Pensions footnote).

V. Swett, Colonel Samuel. History of Bunker Hill Battle (1825), ‘Notes,’ 24.

VI. Secretary of Commonwealth. Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War (1896-1908), 17:153, listed as ‘Whitemore.’ Also 2-CD Family Tree MakerTM set “Military Records: Revolutionary War.” Includes data from descriptive roll.

VII. Ibid 17:264, under ‘Whittemore.’

VIII. United States Revolutionary War Pensions, NARA, Record Group 15, Series M804. 2670 rolls, Pension #S33896, Roll 2569, Frame 236, affidavit of Solomon Bowman.

IX. Secretary of Commonwealth. Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War (1896-1908), 17:254. Also 2-CD Family Tree MakerTM set “Military Records: Revolutionary War.”

X. United States Revolutionary War Pensions, NARA, Record Group 15, Series M804. 2670 rolls, Frame 230.

XI. Cutter, Benjamin and William R. History of the Town of Arlington, Massachusetts formerly the Second Precinct in Cambridge or District of Menotomy, afterward the Town of West Cambridge 1635-1879 … (1880), 202.

XII. United States Revolutionary War Pensions, NARA, Record Group 15, Series M804. 2670 rolls, Frame 225.

XIII. Ibid, Frame 229.

XIV. Ibid, Frame 232.

XV Columbian Centinel (28 January 1826), listed as age 80.