|

Valley Forge National Historical Park Chapter 3 |

|

|

CHAPTER THREE: A Rocky Beginning for the Valley Forge Park Commission (continued) After the controversy over the acquisition of land, the park commission entered a dormant period, precipitated by an almost total lack of funds and no doubt made worse by the depression beginning in 1893. During the second half of 1894, there were few commission meetings because, according to the president's report, there was little business to discuss. [27] Early in 1895, the president reported that the cash awards being made for land were consuming the park's entire appropriation. The commission was so low on operating funds that their watchman had not been paid since December. [28] Francis Brooke's trip to Harrisburg to solicit money resulted in an appropriation of $10,000, but this went toward existing debt, leaving the park commission with no cash to make improvements to the land it had purchased. [29] The park commission report printed at the end of 1896 stated that the park had only $136.72 on hand. The complaint was raised that "no items of personal expenses of any Commissioner incident to the work have been paid from the state funds, though in some instances these items have not been inconsiderable." And the watchman was still waiting for back wages. [30] In 1897, Brooke prepared a report addressed "To the Senators and Representatives of the State of Pennsylvania" asking for $60,000. He bitterly compared the amount of attention Valley Forge was getting with the money dedicated to the preservation of historic sites associated with the Civil War and wrote:

Despite Brooke's efforts, the park commission saw no new funds in 1897 or the following three years. In 1899, Park Commissioner Holstein DeHaven wrote a form letter addressed to "Dear Senator" describing the commission's sad state at that point. "At present I consider that the Valley Forge Commission does not exist," the writer complained, "there being only two members and no officers to carry on the work." By this time Francis Brooke had passed away and another member had resigned. The names of two other potential members had been withdrawn before the state senate had confirmed their appointments. And because there was absolutely no money, those remaining unhappy members of this inactive commission had no means to do their job. The writer concluded: "I think it is a disgrace and a shame to have the present state of affairs existing." [32] The official report of the Valley Forge Park Commission printed at the end of 1900 noted that the commission had been faced with an empty treasury plus bills amounting to $3,500. By this time, the commissioners had also assessed their future needs in caring for the land they had acquired some six years earlier, and estimated their current requirements at $73,200. [33] The following calendar year, the press finally took up the cry that the state legislature had ignored Valley Forge for far too long. The Daily Local News editorialized:

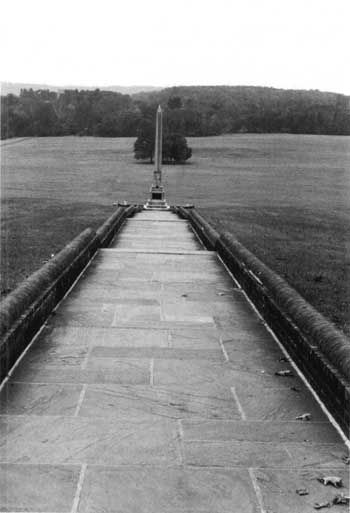

This statement appeared in the same editorial announcing the dedication of an impressive monument at Valley Forge. In 1901, Valley Forge finally got its stone shaft, a marker some 50 feet high and 10 feet square at the base, embellished with a bronze tablet displaying an artist's conception of the Revolutionary encampment. It seemed very much like what the National Memorial Association had envisioned about two decades earlier. For years this monument held the distinction of being the most impressive manmade structure at Valley Forge. It was ironic that in 1901 the new monument was not located within the boundaries of the park, nor did it owe its existence to the impoverished park commission or the stingy Pennsylvania state legislature. Technically the new monument was not really the first monument raised at Valley Forge. That honor belonged to a humble red sandstone marker erected on the left bank of the Schuylkill at the site of a bridge that had been built by Major General John Sullivan. In 1777—1778, this bridge had allowed food supplies to reach the camp from the north. When Washington's army evacuated Valley Forge, they had marched over the same bridge, but the historic structure had been washed away shortly after that. No one knew exactly when or how the sandstone marker got there, but in his 1850 articles on Valley Forge, Henry Woodman mentioned it standing on the opposite shore identifying the location of "Sullivan's Bridge, 1778." [35]

Perhaps inspired by this first marker, in 1840, canal boat workers from the Schuylkill Navigation Company and the Union Canal Works decided to further glorify the former location of Sullivan's Bridge by placing a second marker on the Valley Forge side of the river. At that time, travelers and boatmen could still see the heaps of stone that had been the pilings for Sullivan's Bridge. [36] It may have been during one of the year's idle periods that the boatmen formed a union and began taking subscriptions, eventually raising enough money for a stone that would stand six feet high. Their marker lasted until 1850, when it was washed away. Around that time it was replaced by a local resident, a Dr. William Wetherill. By the end of the century, however, this monument too had been damaged by floods caused by ice breaking up on the river in the springtime, and in no way did it compare with the new stone shaft farther south. [37] Valley Forge's latest monument had been inspired by a small headstone lying in the fields of a Valley Forge farmer named I. Heston Todd, who had long been avoiding it with his plow out of respect for the dead. The headstone was nothing elaborate, but it was the only marked grave at Valley Forge and bore the initials "JW" and the date "1778." As visitors began tramping through the fields and woods at Valley Forge, it became obvious that relic hunters were chipping away at the headstone, The Sons of the American Revolution asked and obtained permission from Todd to protect the relic with a wire cage. It was known that troops from Rhode Island had made camp not far from the headstone, and a letter in the collections of the Rhode Island Historical Society indicated that "JW" was John Waterman, a civilian quartermaster and assistant commissary in General Varnum's brigade. In the late-nineteenth-century atmosphere of ancestor worship, those who could trace their families back to the Revolutionary or colonial era frequently held large, national reunions. Professor Daniel Howard of West Chester used the 1894 Waterman family reunion as an occasion to let Waterman's descendants know about the existence of the headstone. [38] In 1895, Howard received word from the Rhode Island Sons of the American Revolution that the Rhode Island legislature had appropriated $2,000 to erect a monument on Waterman's grave and had established a commission for this purpose. [39] That fall, Francis Brooke got a message from Pennsylvania's Governor Daniel Hastings notifying him that the governor of Rhode Island was coming to Valley Forge to inspect the grave and make further plans for the monument. Brooke was instructed to show the proper amount of respect. [40] Rhode Island's Governor Lippert made it clear that he wanted to cooperate with the Valley Forge Park Commission, but the Waterman grave was not located on ground that had been purchased by the park. I. Heston Todd, who owned the gravesite, had once been a park commissioner, but Governor Hastings had since removed him. Todd was very much at odds with the park commission and was not inclined to cooperate with Governor Hastings. He wanted to see Rhode Island erect a monument to Waterman, but he also wanted to ensure that neither the state of Pennsylvania nor the park commission got any credit for it. He offered to deed a plot of land directly to Rhode Island in return for assurance that its title would never revert to Pennsylvania. He also wanted a piece of the Rhode Island appropriation, although he later denied that he had demanded any kind of payment. If the state of Pennsylvania interfered with his plans, Todd threatened, he would dig up John Waterman and leave the park commission with a worthless plot of land. [41] The park commission countered this threat by trying to lure Rhode Island's appropriation to another site. Declaring that it was unable to deal with the unreasonable demands of Todd, Rhode Island's monument commission had decided to spend an additional $8,000 to erect a bigger and better monument in memory of all Rhode Island soldiers who had served at Valley Forge. The park commission suggested that they put their monument near the site of an old earthwork then called the Star Redoubt (now Redoubt #1), which had commanded the site of Sullivan's Bridge. It was assumed that the site had been defended by Rhode Island men, because their brigade had been encamped immediately east of it while the headquarters of Rhode Island's General James Mitchell Varnum had been located nearby. By 1897, Governor Lippert endorsed this recommendation and the Rhode Island legislature made it law. [42] The site of the old Star Redoubt was on land privately owned by William M. Stephens, whose family had lived in the Valley Forge area for many generations before the Revolution. When the park commission tried to condemn the little more than one acre that Rhode Island's monument would require, Stephens strongly objected to losing a tiny plot from the very center of his farm. He also pointed out that the park commission had no money to finish paying for the land it had already condemned. At the end of 1897, Francis Brooke got a letter from Stephens's lawyer informing him that Stephens planned to contest this condemnation and that no amicable agreement was possible. [43] In 1897, an impartial jury of view put a dollar value on the contested plot, but Stephens tried to get the appointments revoked and the verdict set aside. Finally, Stephens sued the state of Pennsylvania, an action that was sure to incur considerable delay before Rhode Island could start building anything on his land. [44] Indeed, the Stephens case was not called for trial until 1902, [45] at which time a jury awarded Stephens $2,100. The Valley Forge Park Commission report for that year requested the funds it needed to make this payment. [46] By 1904, a Rhode Island monument near the site of the Star Redoubt was still under consideration, but by then the park commission was against it. [47] Notes on negotiations with Rhode Island continued to appear in park commission minutes in 1908 and 1910. [48] Then the 1912 park commission report mentioned that Rhode Island had dropped the entire plan to erect a monument at Valley Forge. By that time, several other states had attractive monuments in place, and the report declared: "Rhode Island may be the last to act as she was the last to act in the adoption of the National Constitution but for such a state of affairs the commission feels that she is alone responsible." [49] In much of the meantime, John Waterman's simple headstone remained neglected, having attracted no other attention than the placement of its wire cage. A 1901 magazine article described its forlorn appearance, mentioning that the cage had not been set over it "for the purpose of keeping John Waterman in, as some irreverent visitor has remarked, but for keeping vandals out. It is rather difficult to understand how relic hunters who came before the cage ever managed to leave as much as they did of this lonely monument." [50] As lonely as Waterman's headstone may have been, the Waterman grave itself was located on a slope where it seemed that the faint outlines of many other unmarked graves could still be made out, equally forlorn and deserving of some sort of recognition. [51] In 1897, members of an organization called the National Society, Daughters of the Revolution of 1776 began negotiating with I. Heston Todd, taking up where the state of Rhode Island had left in efforts to glorify the spot with a monument. To them, Todd conveyed the land he had wanted to give to Rhode Island, and the organization established a fund and began receiving donations. [52] Before his death in office, President McKinley had supported the daughters in their patriotic efforts. The daughters unveiled their shaft in October 1901, and had President McKinley lived he would probably have attended. As it was, Pennsylvania's governor was there to witness the dedication. [53] From the very day it was dedicated, this monument has confused many a visitor. Even today, it is popularly but incorrectly called the "Waterman Monument," and few are certain exactly what it is dedicated to. It was never intended as a monument solely to John Waterman. It was erected on the site of one of Valley Forge's supposed burial grounds and was dedicated to all those who died at Valley Forge. Its inscription reads: "To the memory of the soldiers of Washington's army who sleep in Valley Forge." Yet even the park commission indicated confusion in their 1902 report when they described it as a memorial to "the endurance of the Revolutionary Patriots who during this severe winter, underwent the hardships incident to the severe cold, and withstood the ravages of disease which almost wiped the army out of existence." [54] On the contrary, the area's first impressive monument was dedicated to those at Valley Forge who did not endure, withstand, or survive. The obelisk was not intended to replace Waterman's headstone, which continued to stand nearby until 1939, when park commissioners were alarmed to discover it missing. Upon learning that the daughters had removed it and planned to donate it to a museum, park commissioners convinced the organization's officers to transfer its ownership to themselves so that it could be placed in the park museum. It is now the property of the National Park Service at Valley Forge, and its former location has become uncertain. [55] The fanfare over the striking new monument overshadowed the private placement that same year of another grave marker at Valley Forge. Local resident R. Francis Wood had unearthed some bones on his farm and had written park superintendent A. H. Bowen for permission to inter them on park property. He wrote: "They are the remains of a soldier of the Revolutionary Army, who was shot on the farm by the then owner, presumably for stealing and with the authorization of a continental officer. [56] Permission was granted, and Wood buried the soldier near the redoubt then called Fort Huntington (now Redoubt #4), putting up a simple stone, which actually became the first monument in the new park. Today, park rangers refer to it as the "chicken thief monument." At the turn of the century, the park at Valley Forge was essentially without impressive markers and interesting structures like Washington's Headquarters. What did it have? The park commission had purchased a strip of land along the river that connected to a pentagon-shape area bordered today by Route 23, North Gulph Road, and Baptist Road Trace. This adjoined a triangular area situated between Valley Creek and the line separating Chester and Montgomery counties. On park land were the two major lines of earthwork entrenchments that once formed the inner lines of defense against potential attack at Valley Forge. There were also two redoubts that the park had named Fort Washington (now Redoubt #3) and Fort Huntington (now Redoubt #4). The park essentially consisted of mounds and depressions in the earth indicating where something had once been. The park was a wild place, so overgrown that even park personnel had not fully explored it. In 1897, park guard Ellis Hampton wrote Francis Brooke: "As I was walking over the hills I discovered, what seemed to be, a line of entrenchments. They lie in the tract of Mahon Ambler on the Southeast side of the hill, 300 feet east of the long line of entrenchments." [57] The need for better care of Valley Forge was heightened by turn-of-the-century improvements in transportation that were bringing more and more visitors to the area. In the 1890s, Valley Forge got a second railroad station on the south side of the tracks that was soon surpassed by a new stone building constructed in the early 1900s. Valley Forge narrowly missed getting trolley service when the Phoenixville and Bridgeport Electric Railway Company tried to lay tracks through the park. This project apparently languished because the park commission said it did not have the power to grant right-of-way. The matter was referred to the state attorney general and was promptly strangled by red tape. [58] At the turn of the century, visitors arrived at Valley Forge to pay tribute to traditional American ideals in a changing society. In a popular novel published in 1906, Lady Baltimore, author Owen Wister has two characters discuss exactly what was wrong with contemporary Americans. "They've lost their sense of patriotism," one character asserts. People were only interested in making money, and these upstarts had a notorious lack of respect for their betters, the people of formerly powerful and prominent families. Yes, there were "those who have to sell their old family pictures [and] those who have to buy their old family pictures." Not only that, but the South had its "Negroes" to contend with, while the North had its "low immigrant groups." [59] What would become of America? America needed places like Valley Forge. The park commission needed an infusion of money if it was to shape the land it had acquired there and enhance appreciation of the Valley Forge experience. |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

Valley Forge ©1995, The Pennsylvania State University Press treese/treese3a.htm — 02-Apr-2002 | ||