|

Valley Forge National Historical Park Chapter 3 |

|

|

CHAPTER THREE: A Rocky Beginning for the Valley Forge Park Commission While the Centennial and Memorial Association struggled to acquire and maintain its historic house, it focused enough attention on Valley Forge for other groups and individuals to engage in a kind of debate about exactly what constituted a fitting tribute to the winter encampment of 1777—1778. What should be preserved of this holy ground? And what should be added to the landscape? Having lost her wealthy ambassador husband to death, Mary E. Thropp Cone, who had written a poem for Evacuation Day 1878, returned to her native Pennsylvania. In June 1882, while the Centennial and Memorial Association was desperately trying to raise funds for Washington's Headquarters, she wrote a lengthy letter to the Phoenixville Messenger, its prose no less poetic than her verse:

Editor and publisher John O. K. Robarts took up where Mrs. Cone left off. One week later, he wrote:

In the second half of the nineteenth century, monuments were springing up at many historic sites, a trend that peaked between 1870 and World War I, a time of intense nationalism in the United States. On historic battlefields, monuments marked troop positions and enabled visitors to mentally re-create the honor and glory of great battles. They acknowledged the memorable deeds of heros and warriors and ennobled the sacrifice of life, allowing contemporary people to demonstrate their allegiance to the ideals of the past. [3] As Mrs. Cone had noted, other historic sites associated with the Revolution already had imposing and enduring granite shafts, but Valley Forge had none. Thanks to agitation by Mrs. Cone and Robarts, Valley Forge soon had a new organization. On December 18, 1882, Mary E. Thropp Cone organized a meeting at the public hall in the village of Valley Forge to celebrate the 105th anniversary of the winter encampment and to see that Valley Forge would soon get the monument it deserved. Robarts reported that those she gathered together resolved that "Valley Forge should have a monument to perpetuate the memories of the Continental heroes who suffered here" and added: "It is to be earnestly hoped that a Soldiers' monument upon the heights of Valley Forge will be the result of the meeting brought about by that sterling lady, Mrs. Mary E. Thropp Cone." [4] By the following spring, Mrs. Cone's organization had a charter and a name: The Valley Forge Memorial Association. Naturally, Mrs. Cone was elected president. She proposed to raise $5,000 by private subscription and reported that her group had already collected about $500. [5] They must have been greatly encouraged when, within a year, Congress considered a bill encouraging the erection of monuments on Revolutionary battlegrounds. This proposed bill would enable the U. S. Treasury to match dollar for dollar the funds raised by any historical association that could collect $5,000 to this end. Although the Valley Forge Memorial Association failed to achieve its purpose and soon disbanded, Mrs. Cone's efforts may have had other effects on Valley Forge. Her fundraising coincided with the period during which the Centennial and Memorial Association had the greatest difficulty collecting money and despaired that their mortgage might be foreclosed on. It is possible that the Valley Forge Memorial Association actually drew money away from headquarters. A Valley Forge guidebook published in 1906 hinted at another effect, suggesting that when the Valley Forge Memorial Association failed to raise the money it needed for a monument from the federal government, they turned to the state of Pennsylvania, abandoned the monument idea, and joined in agitation for a large public-land reservation at Valley Forge. [6] By the end of the nineteenth century, other voices besides those of Centennial and Memorial Association members were calling for the actual site of the winter encampment at Valley Forge to be preserved as some sort of park. One of the earliest came from Theodore W. Bean, author of Foot Prints of the Revolution and member of the Centennial and Memorial Association, who proposed that his own organization purchase the campground, the funds again being supplied by POS of A. [7] When the 190-acre Carter Tract was offered for sale, a Daily Local News editorial asked: "What shall be done with historic Valley Forge? The beautiful tract of land which recalls memories of patriotic devotion seldom, if ever, equalled in the history of America, has long been private property, and of recent years has almost gone begging for some one to buy it." The newspaper suggested two alternatives: "That the Society of the Daughters of the Revolution, of which Mrs. Benjamin Harrison is President, shall acquire the property, and the second, that it shall be reserved, either by the state of Pennsylvania or the Federal Government, as a park." [8] The park movement found a successful champion in Francis M. Brooke, a descendant of General Anthony Wayne. In the 1890s, Brooke was a state legislator and committee chairman. He had attended the Centennial celebration in 1878 and was among the thousands who had been inspired by the moving words of Henry Armitt Brown. In 1892, he began lobbying Harrisburg for legislation to establish a state park at Valley Forge, which resulted in a bill signed by Governor Robert E. Pattison in 1893 creating the Valley Forge Park Commission. The state legislature also appropriated $25,000 to enable the park commission to buy roughly 250 acres of the land on which Washington's army had camped and where the earthworks the army built in 1777—1778 were still visible. After Brooke's death in 1898, the minutes of the park commission offered this tribute: "To his patriotic interest in the preservation of the memorials of the Revolutionary struggle this Commission owes its origin." [9] The Valley Forge Park Commission was a ten-man committee whose members were directly appointed by the governor for five-year terms with no compensation. The first park commission consisted of prominent Philadelphia businessmen as well as officers of historical and patriotic associations, such as the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the Society of the Cincinnati. It met for the first time on June 17, 1893, at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and elected Francis Brooke as their president. Though they were important and knowledgeable men in their own fields and organizations, they realized they had but surface knowledge of Valley Forge, so they resolved to visit the campground together with members of another patriotic organization called the Pennsylvania Sons of the Revolution. [10] The statute creating the Valley Forge Park Commission said that the state itself was appropriating land at Valley Forge. The original task of the park commission was to establish the boundaries of this park by determining exactly where Washington had positioned his men and built his defensive earthworks. Its ongoing task was to preserve this land forever as nearly as possible in its "original condition as a military camp." Land where Washington's soldiers had camped automatically belonged to the state of Pennsylvania. [11] Although its former owners would be compensated, they had no choice but to sell. The commission was also empowered to maintain the park as a public place and to make its historically important sites accessible to visitors. The 1893 statute specifically excluded land already owned by the Centennial and Memorial Association. Francis Brooke wrote Frederick Stone, a fellow park commissioner and officer of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, that their first task would be to draw a map of the Revolutionary campground "according to the best obtainable information." [12] To do this, they also needed to know exactly what had happened at Valley Forge, but they quickly discovered that little real documentary research had ever been done. Their task would necessarily begin with the collection of information. Brooke sent a letter to every major library and historical society in the nation, requesting that all known maps and information be referred to the park commission. [13] The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, published by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, advised its readers that the Valley Forge Park Commission was "aware that there are many unpublished original documents relating to the camp, and [was] desirous of obtaining the deposit of orderly-books, diaries, letters, and maps, for preservation and for the further elucidation of its history." [14] When the park commissioners began their work, the earliest known research on maps of Valley Forge was that Jared Sparks did for his biography of George Washington. In 1833, Sparks had drawn a map based on the personal recollections of a Valley Forge resident. The Sparks map had come into the possession of Cornell University. In the 1890s, several exciting map discoveries came to the attention of the Valley Forge Park Commission. Samuel W. Pennypacker—son of Isaac A. Pennypacker, who had made one of the earliest calls for the preservation of Valley Forge in his letter to John Fanning Watson in 1844—was traveling in Europe. In Amsterdam, Pennypacker was able to purchase an original set of drafts and plans drawn by a French engineer during the Revolutionary period, among which, he was delighted to discover, was a contemporary map of Valley Forge. He told of his discovery in an address to POS of A members delivered in 1898 when he presented the precious map to their organization. [15] The map is now in the collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Valley Forge's most famous map was apparently discovered at about this time by Lawrence McCormick. This map had been hidden in a nearby old residence called the John Havard House. The handwriting on it was similar to that of Washington's chief engineer, French Brigadier General Louis Duportail, who had lived in the Valley Forge area from 1795 to 1801. This map, which is known as the "Duportail map," also ended up in the collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Though hailed as a monumental discovery, a copy of the Duportail map was already among Jared Sparks's materials, so apparently its existence was known during the lifetime of this scholar. [16] In 1893, the Valley Forge Park Commission hired an engineer named L. M. Haupt to conduct a topographical survey of 460 acres "more or less" in the roughly triangular tract of land between the Schuylkill River, Valley Creek, and Washington Lane (now Baptist Road Trace). [17] Based on their ongoing documentary research and this topographical study, the commission began to lay out the boundaries of the 200-odd-acre park and to identify the current private owners of this land. The Valley Forge Park Commission then attempted to obtain the land they wanted at the lowest possible cost and least possible inconvenience to its present owners. As recently as 1891, the Daily Local News had speculated: "Land in this vicinity is not regarded as high in price, and the owners of the Valley Forge property are said to be anxious to sell." This newspaper account, written two years before the park commission had been created, estimated the value of land at Valley Forge at about $10 an acre. [18] The park commission optimistically sent letters to current owners asking them to name their price. [19] To the dismay of its members, the park commission discovered that the perceived value of land at Valley Forge had increased sharply in the brief time since their organization had been established. Local landowners got little sympathy from the area press. The Daily Local News quoted the Media Record in castigating owners who "fondly hug the delusion that [the State] will pay fabulous prices for what is little more than scrub land at best. . . . To now attempt to extort fabulous prices for this ground savors strongly of a spirit and purpose that is grossly mercenary, if not actually mean." [20] Rather than haggle with owners, the park commission worked to establish independent county "juries of view" to examine the land in question and determine its value. In February 1894, the Montgomery County jurors met at the Washington Inn at Valley Forge and went as far as they could up the overgrown hillsides by carriage, "and thence on foot, through the mud, brush and rain," carefully examining the actual ground for themselves. [21] The juries also met with witnesses called by landowners and the park commission both.

The owners and their partisan witnesses made some interesting claims. George McMenamin, son of landowner B. F. McMenamin, testified that just eighteen acres of Valley Forge farmland had produced some 1,800 bushels of corn in a single season. A newspaper sarcastically reported: "Such a remarkable yield had never before been heard of by the jurors or the Park Commissioners' counsel, and they were inclined to believe that George was mistaken. The witness, however, adhered to his statement during a rigid cross-examination." [22] Other owners testified that their holdings had potential as possible quarries or that valuable deposits of potters' clay lay just beneath the surface. The prices claimed by private owners and their witnesses were fully 50 percent higher than those claimed by witnesses for the park commission. The owners continued to be blasted by the press for their lack of patriotism and apparent intent to fleece the taxpayers of Pennsylvania. The Daily Local News quoted the Phoenixville Messenger: "It is strange that when people who appear to be surcharged with patriotism have a chance to put money in their pockets they forget the bonny Red, White and Blue, and become grabbers of the most heroic stamp." [23] A few weeks later, the same paper quoted the Lancaster New Era: "It [the original appropriation for the park] looked like a fat goose to these land owners, and they resolved it would not be their fault if that goose was not well plucked." [24] By October 1894, all the testimony was in and the jurors made their reasonably impartial valuations. Land in Montgomery County would be sold for an average of $135.01 an acre, and land in Chester County would be sold for an average of $169.12 an acre. [25] This was more than the park commission had originally expected to pay, but it was also less than half of what some owners had expected to receive. The Daily Local News concluded: "The people of the State will be glad to learn that it is possible to carry out a patriotic project in spite of the attempts of a few to make money out of it." [26] |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

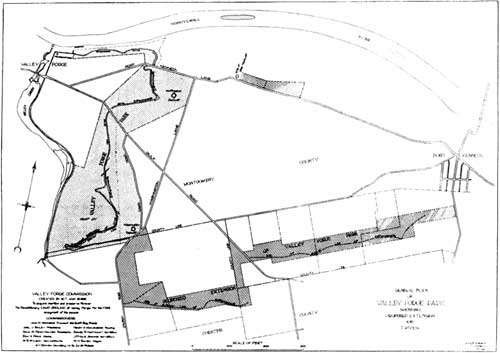

Valley Forge ©1995, The Pennsylvania State University Press treese/treese3.htm — 09-Apr-2002 | ||