Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings

|

FORT DAVIS NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE Texas |

|

| ||

The picturesque remains of Fort Davis, more extensive and impressive than those of any other southwestern fort, are a vivid modern reminder of a colorful chapter in western history. They also stand as a tribute to the courage of frontier soldiers, black and white, and their tenacious Indian opponents. A key post in the western Texas defensive system, Fort Davis was one of the most active in the West during the Indian wars, especially the 1879-80 campaign against the Apache Victorio. As Fort Bowie, Ariz., spearheaded the campaign against the Chiricahua Apaches, so did Fort Davis against the Warm Springs and Mescaleros. Forts Bowie and Davis also both protected transcontinental emigrant, freight, and stage routes.

The mounting tide of westward travel in the 1850's, generated by the California gold rush and the newfound interest of settlers in the vast territory the United States acquired from Mexico in the Mexican War (1846-48) and the Gadsden Purchase (1853), swelled traffic over the transcontinental trails. To avoid the winter snows and mountains of the central routes to the goldfields or to seek their fortune in the newly acquired Southwest, thousands of gold seekers and emigrants pushed along the southern route. A vital segment was the San Antonio-El Paso Road, opened in 1849, which also carried a large volume of traffic between the two cities and Santa Fe, N. Mex., and Chihuahua, Mexico.

|

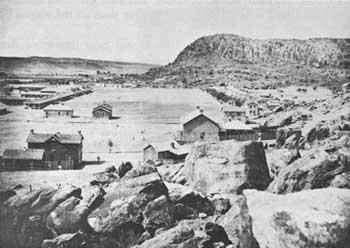

| Fort Davis about 1885. (National Archives) |

The road presented rich opportunities for plunder to Kiowa, Comanche, and Mescalero Apache raiders. Intersecting it were the trails of marauding Indians who had long swept down from the north and devastated the isolated villages and haciendas of northern Mexico. West of the Davis Mountains, foraying Mescaleros of New Mexico crossed the road. East of the mountains, the Great Comanche War Trail bisected its lower branch at Comanche Springs.

Inevitably the Indians paused to assail travelers on the San Antonio-El Paso Road. As depredations mounted, a finger of military outposts pointed west into the trans-Pecos region. Forts Hudson, Lancaster, Stockton, Davis, Quitman, and Bliss extended military protection from the outer ring of defensive posts all the way to El Paso.

Of these, Fort Davis was the largest and most important. Lt. Col. Washington Seawell and 8th Infantry troops from Fort Ringgold, Tex., founded it in 1854 near a site known as Painted Comanche Camp. At the eastern edge of the Davis Mountains north of the Big Bend of the Rio Grande, the new fort was situated in a small box canyon, lined by low basaltic ridges, just south of Limpia Canyon. Strategically located in relation to emigrant and Indian trails and on the San Antonio-El Paso Road, it also afforded an adequate water supply, mandatory in the arid region, from nearby Limpia Creek; a good timber supply, for fuel and construction, in the Davis Mountains; and a salubrious climate. Seawell never built the more permanent post he envisioned to the east at the mouth of the canyon. Instead, in time a motley collection of tent-like structures and thatch-roofed buildings of log, picket, frame, and stone straggled along the length of the canyon.

|

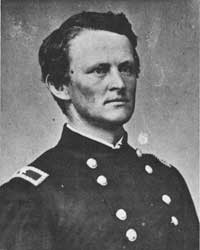

| Lt. Col. Wesley Merritt and his black 9th Cavalry troops reactivated Fort Davis in 1867. He later won distinction during the northern Plains campaigns. (photo Matthew B. Brady, National Archives) |

In the pre-Civil War years the garrison patrolled regularly, guarded mail relay stations, escorted mail and freight trains, and fought occasional skirmishes with the Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches. The troops made little progress, however, in pacifying the Indians in the region. Tempting targets to the warriors were the mail-carrying stagecoaches that operated on a local and interregional basis in the 1854-61 period through Fort Davis over the San Antonio-El Paso Road and offered connections with St. Louis, Santa Fe, and California: the George H. Giddings (1854-57) and James Birch (1857-61) lines, and the Butterfield Overland Mail (1859-61).

One of the few diversions of the fort's troops, whose duties were alternately grueling and boring, was watching the camels of the Army's experimental corps that occasionally lumbered in. Edward F. Beale's herd of 25 en route in 1857 from the Camp Verde camel base to Fort Tejon, Calif., passed by. In 1859 and 1860 Texas military authorities utilized some of the Camp Verde animals in an attempt to blaze a shorter route from San Antonio and the Pecos to Fort Davis and to compare their efficiency with mules. Although the camels proved superior, the camel project ultimately came to naught.

The Union evacuated its forts in western Texas in 1861, when Texas joined the Confederacy. The Confederates took over Fort Davis in 1861-62, but withdrew upon their failure to conquer New Mexico and the approach of General Carleton's California Volunteers. Meantime the men in grey had enjoyed no immunity from the Apaches, who wiped out a detachment of 14 of them deep in the Big Bend country. Wrecked by Apaches, Fort Davis lay deserted for 5 years.

Federal soldiers, under Lt. Col. Wesley Merritt, did not return until the summer of 1867, but when they did their color had changed. Between then and 1885, elements of all the Army's post-Civil War black regiments, composed largely of ex-slaves and commanded by white officers, were stationed at the fort at one time or another along with various white regiments. The black units were the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry, all of which served with notable distinction not only at Fort Davis but throughout the West during the Indian wars.

Rather than trying to rebuild the old fort, which had been vulnerable to Apache attacks from closeby ridges, Merritt fulfilled Seawell's dream by beginning the erection of a new fort at the mouth of the canyon. Of more substantial stone and adobe, it was not completed until the 1880's. Meantime Fort Davis had resumed its role of protecting western Texas. Highlighting the achievements of the fort's black troops, as well as those from other Texas forts, was participation in the Victorio campaign (1879-80). As many as 1,000 troops, a large number of them black, at various times tramped 135,000 miles in the arduous but frustrating pursuit of Victorio's tiny group of some 100 Warm Springs and Mescalero Apaches.

|

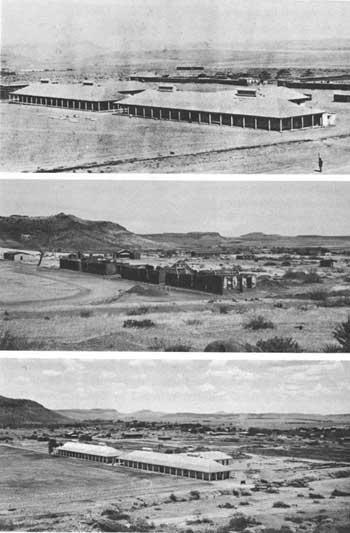

| Barracks at Fort Davis. Top, in 1875; center, 2 years before the National Park Service began restoration; and bottom, following restoration in 1965-66. (National Archives (top), National Park Service (middle and bottom)) |

In the spring of 1879 Victorio, who for 2 years had resisted the efforts of Indian agents to move his band to the San Carlos Reservation, Ariz., recruited some of the discontented Mescaleros at the Fort Stanton Reservation, N. Mex., who had been raiding in Texas themselves. The new allies, outrunning pursuing troops, fled into Mexico. For 2 years, employing clever guerrilla tactics, they wreaked havoc on both sides of the Rio Grande and struck repeatedly in New Mexico, western Texas, and Chihuahua (Mexico). When cornered, they skirmished with soldiers, Texas Rangers, and citizens' posses, but always managed to escape. In September 1879 and January 1880 Victorio returned to New Mexico. On the latter occasion, New Mexico and Texas troops attempted to disarm the Mescaleros at Fort Stanton Reservation before Victorio could recruit them. But 50 of them escaped and joined Victorio, who returned to Mexico.

Knowing that Victorio would appear again but preferring to stop him in Texas rather than sending troops to New Mexico, Col. Benjamin H. Grierson in the summer of 1880 established the headquarters of his black 10th Cavalry at Fort Davis; dispersed troops all along the arid country from there to El Paso; sharpened patrol actions; set up subposts along the Rio Grande at Viejo Pass, Eagle Springs, and Fort Quitman; and carefully watched the waterholes Victorio would need to rely on to cross the inhospitable country.

|

| Col. Benjamin H. Grierson, commander of the black 10th Cavalry. Fort Davis was a key base in his vigorous 1879-80 campaign against the Warm Springs Apache Victorio. (Kansas Historical Society) |

Finally, in the vicinity of present Van Horn, Tex., Grierson and his men defeated Victorio in two battles in July and August and forced him back into Mexico. Two months later Mexican soldiers killed him. A remnant of his band, under the aged Warm Springs leader Nana, escaped to the Sierra Madre, where they later joined forces with another wily Apache leader, Geronimo. But Victorio's death ended the era of Indian warfare in Texas.

In the 1880's large numbers of cattlemen settled in the area of the fort. The routine was punctuated only by occasional tours of escort duty for railroad builders, bandit-chasing expeditions, and border-patrol actions. The routes of the Texas Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroads, which pushed through western Texas in the 1880's, bypassed the fort. The last troops left in 1891.

In 1963 Fort Davis came into the National Park System. A program was immediately launched to save the remaining buildings, begin restoring some of them, and interpret the story of the fort to the public. Of the more than 50 adobe and stone buildings that constituted the second Fort Davis at the time of its abandonment, visitors today may inspect 16 officers' residences, two sets of barracks, warehouses, a magazine, the hospital, and other structures. Stone foundations mark the sites of other buildings. Archeologists have recently uncovered the foundations of many structures of the first fort (1854-61), in the canyon west of the second. The site of the Butterfield stage station, a half mile northeast of the first fort, has also been identified. The National Park Service presents a unique sound program of special interest to the visitor. He may hear a bugle, echoing from the nearby hills, peal out the various orders of the day. Another interesting sound presentation is a formal retreat ceremony.

NHL Designation: 12/19/60

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/sitea23.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005