Historical Background

As the 19th century opened, the Indians of the trans-Mississippi West unknowingly stood on the threshold of ethnic disaster. An alien tide rolled westward. Within a century it would engulf all tribes, appropriate all but a tiny fraction of their vast domain, and leave the survivors a way of life often grotesque in its mixture of the old and the new. The tribes east of the Mississippi were already suffering this experience. They were being pushed ever westward by the advancing frontier; or left in isolated pockets surrounded by hostile conquerors; or simply annihilated; or, in rare instances, absorbed by the newcomers. A few western tribes, notably in Spanish New Mexico and California, had experienced something of what was to come. Of the rest, only the occasional visit of a French or Spanish trader kept them from forgetting that white men even existed.

Even so, the western Indian had already received two significant gifts from the white man. The horse, filtering up through successive tribes from the Spanish borderlands, revolutionized an older way of life and gave a new mobility to many nomadic and seminomadic hunting groups. This gift caused important changes not only in their economy but also in their social, ceremonial, and material organization. The Indians who confronted the 19th-century American had inhabited the West for centuries; their culture, because of the horse, had only recently taken the shape known to frontiersmen. The second gift, the gun, had by 1800 demonstrated its utility in war and the hunt to a few northern tribes bordering the French frontier but had yet to find its way into the hands of very many warriors. For horses the Indians were now beholden to no alien race; for guns they were soon to become dependent on the white man.

Not all tribes felt these influences equally. On the Great Plains the impact of horse and gun produced its highest cultural expression among the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Kiowa, Comanche, Pawnee, and lesser-known tribes. In the Rocky Mountains, Nez Perces, Flatheads, Utes, Shoshonis, Bannocks, and others conformed only slightly less exactly to the prototype. By contrast the Pueblos of the Rio Grande drainage remained agriculturalists living in fixed dwellings. The Navajos became superb horsemen but also cultivated crops and tended herds of sheep—a legacy of Spanish times. Their neighbors, the Apaches and Yavapais, traveled their mountain-and-desert homeland by foot as often as by horse and mule; they also planted crops. The Paiutes and Western Shoshonis of the Great Basin displayed similar patterns. In the mountains of the Far West and along the Pacific coast, a woodland and marine environment, traditional hunting, gathering, and fishing customs made only minor accommodations to European technology.

As the trickle of western migration swelled to a flood in the first half of the 19th century, the western Indians, as had their eastern brethren earlier, only dimly sensed the alternative responses open to them. [Indian affairs east of the Mississippi and pertinent sites are discussed in Founders and Frontiersmen, Volume VII in this series; those in Alaska, in Pioneer and Sourdough, planned Volume XIII. (Web Edition Note: This title was never published.] They could unite in a desperate war to turn back the invaders. They could submit, borrowing from the invaders what seemed best and rejecting the rest. Or they could give up the old and adopt the new. The first choice usually proved impossible because of traditional intertribal animosities and the independence of thought and action that characterized Indian society. The last was rarely considered seriously. Sooner or later most of the tribes turned to the second, but few succeeded. For most groups, instead, the old culture simply disintegrated under the foreign onslaught—sometimes with, sometimes without, armed resistance—and left a void imperfectly and unhappily filled by parts of the conqueror's way of life.

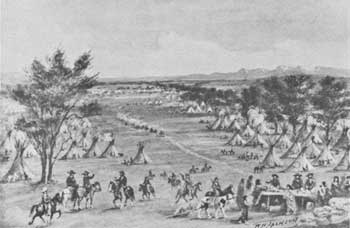

|

| Trappers' rendezvous on the Green River in Wyoming. The fur traders introduced the Indians to the white man's ways. William H. Jackson painting. (Utah Historical Society) |

In the wake of the official Government explorers—Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, Zebulon Pike, Stephen H. Long—came the roving fur trappers. [The fur trade and associated sites are treated in Trappers, Traders, and Explorers, planned Volume IX in this series. Web Edition Note: This title was never published.] Spreading through the wilderness, they afforded the Indian his first sustained view of the whites. Generally he liked what he saw, for many of the trappers in fact "went Indian," adopting many Indian tools, techniques, customs, and values. But the trappers also presented only a blurred glimpse of the manners and customs of the white men. Free and company trappers roamed the West until the early 1840's, but the fur business came to be dominated by the fixed trading post, which relied on the Indian to do the actual fur gathering.

At Fort Union on the upper Missouri, at Bent's Fort on the Arkansas, at Fort Laramie on the North Platte, at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia, and at a host of lesser fur posts sprinkled over the West, Indian and white met on the latter's own ground. There the Indian acquired a fondness for alcohol that made it the chief tool of competition between rival companies, and there he contracted diseases such as smallpox and cholera that decimated tribe after tribe. There, too, the white man's trade goods—guns, kettles, pans, cloth, knives, hatchets, and a whole range of other useful items—fundamentally affected the Indian's material culture and thus bound him to the newcomers. There after, even in time of war with the whites, he looked to them for a large variety of manufactures that had come to be regarded as essential.

|

| As time went on, traders came to rely on fixed trading posts, to which the Indians brought their furs. Interior view of Fort William (Fort Laramie), Wyo., about 1837. Watercolor by Alfred Jacob Miller. (Walters Art Gallery) |

Despite occasional armed clashes, the trapper-traders and the Indians usually dwelt compatibly side by side. Neither was bent on dispossessing or remaking the other. By the early 1840's, however, the Indian observed, coming from the East, other kinds of white men—miners, farmers, stockmen, adventurers of every breed—who did pose a threat to all he treasured.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/intro.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005