Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings

|

GUADALUPE MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK Texas |

|

| ||

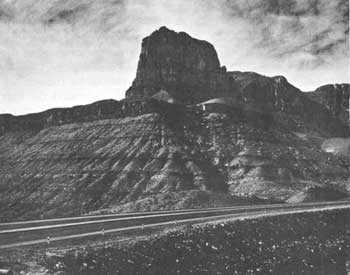

The lofty peaks identifying this new national park, notable primarily for its natural features and geological phenomena, rise dramatically from the desert floor. Although the greater part of the Guadalupe Mountains lie in New Mexico, the highest peaks, those comprising the national park, are in Texas. Indeed, they are the highest in the State. Historically, the mountains were a stronghold of the Mescalero Apaches.

In 1849, by the time of the California gold rush, western Texas was a vast stretch of wilderness that few Americans had seen. West of San Antonio, the barren and rocky desert, broken only by a series of rugged mountains, was inhabited mainly by Lipan and Mescalero Apaches. For two decades other Indians, bands of Mescaleros from New Mexico and Kiowas and Comanches from Indian Territory, had traversed the area on forays into Mexico to obtain food. This pattern prevailed until the 1850's.

After the discovery of gold in California, gold seekers poured over the upper and lower branches of the San Antonio-El Paso Road, surveyed in 1849. But lightning-like Mescalero raids hampered travel over both routes. In 1854, to guard the lower branch, which passed through the Davis Mountains, the Army established Fort Davis, Tex., but left the upper road, which ran along the southern end of the Guadalupe Mountains, unguarded. In 1855, while the Fort Davis garrison gave the Mescaleros no surcease, New Mexico troops campaigned against them in the Sacramento and Capitan Mountains of New Mexico. As a result, most of them settled on a reservation near Fort Stanton, N. Mex. A few bands continued to live in the Guadalupe and Davis Mountains and in the Chisos Mountains of the Big Bend. These groups resumed raiding roads in Texas and villages in Mexico, sometimes with the aid of their kinsmen from the reservation.

The Butterfield Overland Mail in 1858 won a Government contract to deliver mail from St. Louis to San Francisco. The company chose a southern route, a portion of which followed the upper branch of the San Antonio-El Paso Road. In a pass at the foot of the Guadalupes, a stage station was erected and called Pine Springs (Pinery). The next year, however, seeking the protection of Fort Davis, the Butterfield line moved to the lower branch. In 1861, when the Army evacuated Fort Davis and the other forts in western Texas, the company abandoned the southern route altogether in favor of a central one. The roads lay at the mercy of the Indians.

|

| El Capitan, Guadalupe Mountains National Park. (National Park Service) |

The Army reactivated Fort Davis in 1867 and renewed its efforts to curb Mescalero raids. These had increased because in 1865 the Mescaleros had fled a new reservation in eastern New Mexico, near Fort Sumner, where they had been confined in 1862-63. They continued to use the Guadalupes and their other mountain haunts to regroup and resupply for their forays into Mexico. To patrol such a large area more effectively, Fort Davis set up a number of subposts at the more important waterholes. One of these subposts was Pine Springs, the old Butterfield stage station.

In 1869 Col. Edward Hatch took over command of Fort Davis. The next year, determined to curb the Mescaleros once and for all, he launched an offensive, supported by other Texas and New Mexico posts. He led three patrols from Fort Davis northward into the Guadalupes. Only once did his men make contact with the Indians, in January, when a group of them surprised and inflicted severe casualties on an Apache camp. This action convinced the Mescaleros that the Guadalupes were not as safe as they had believed. Late in 1871 the principal bands reported to the Fort Stanton Reservation. But the calm was of short duration.

In the last half of the 1870's the Mescaleros erupted again, leaving the reservation and returning to the remote canyons of the Guadalupes and other ranges in the trans-Pecos region. They resumed raiding in Texas and Mexico. The reasons for the new unrest included the pressure of white settlement around the Fort Stanton Reservation, the unsettling influence of the cattlemen's war in Lincoln County, N. Mex. (1878), and the growth of factionalism among the reservation Mescaleros.

Many of the Mescaleros joined the Warm Springs Apache Victorio, whose band roved back and forth between Mexico, Texas, and New Mexico and terrorized the borderland in 1879-80. To little avail, troops in the Victorio campaign often scoured the Guadalupe and Sacramento Mountains looking for the adversary. During the summer of 1880 the Army repelled Victorio in the Battles of Tinaja de las Palmas and Rattlesnake Springs, Tex. The latter battle was fought within sight of the mighty peaks of the Guadalupe Mountains, for which the Indians were heading and from which a group of Mescaleros had been riding to reinforce Victorio when troops intercepted them. Soon thereafter Mexican troops killed Victorio, whose death marked the end of the Mescalero insurgency and the Indian wars in Texas.

Guadalupe Mountains National Park, authorized in 1966, is a new National Park Service area. Traces of the dry-masonry stone walls of the Pine Springs stage station and military subpost remain on U.S. 62-180 at the base of the landmark known as El Capitan. Behind the ruins are a weed-choked well.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/sitea24.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005