Historical Background

The Oregon country, its ownership disputed between Great Britain and the United States, attracted some; Mexican California others. Then in the Mexican War (1846-48) the United States seized California and the Southwest from Mexico and extended its dominion to the Pacific. Texas, independent of Mexico since 1836, joined the Union in 1845. Settlement of the Oregon controversy in 1846 added the Pacific Northwest.

Territorial expansion stimulated emigration. The dramatic discovery of gold in California in 1848 opened the floodgates. Bound for the new possessions, few emigrants stopped to make their homes in the Indian country, but they pierced it from north to south with a tier of overland highways—the Oregon-California Trail, the Santa Fe Trail, the Gila Trail, the Smoky Hill Trail, and a multitude of alternate and feeder trails.

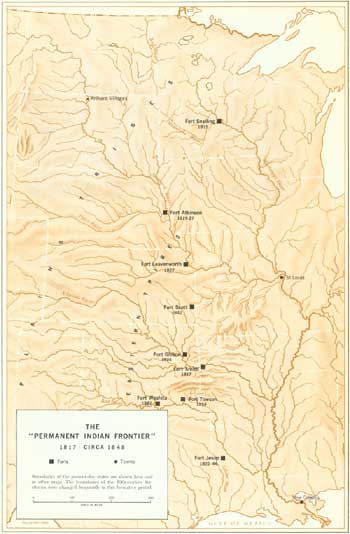

The overland trails destroyed a dream cherished by statesmen since the 1820's. They hoped to solve the Indian problem by erecting a "Permanent Indian Frontier," beyond which all tribes could enjoy security from invasion. To define the frontier, the Army laid out a chain of posts, running from Fort Snelling, Minn. (1819), on the north, to Fort Jesup, La. (1822), on the south. Roughly paralleling the eastern boundary of the second tier of States west of the Mississippi, it eventually extended through Forts Atkinson (1819), Leavenworth (1827), Scott (1842), Gibson (1824), Smith (1817), Towson (1824), and Washita (1842). Most of the eastern Indians were moved to new lands west of the frontier. Congress enacted a comprehensive body of legislation, the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act of 1834, to regulate relations with both immigrant and resident tribes. In 1838 Indian Territory—roughly modern Oklahoma—was established as a permanent home for the dispossessed easterners.

But in the 1840's the western trails breached the "permanent frontier" and bore streams of travelers across it. They demanded protection. By 1850 the "permanent frontier" had vanished and the Federal Government had moved west to confront the Indian. Along the trails and among the settlements at trail's end, the Army built forts. The Indians met new types of men—soldiers, agents, peace commissioners—who turned out to be not nearly so agreeable as the trappers and traders.

|

| The "Permanent Indian Frontier" (1817-circa 1848) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The agents and peace commissioners represented the Government Agency charged with Indian relations: the Indian Bureau, transferred in 1849 from the War Department to the newly created Department of the Interior. They negotiated treaties, disbursed annuity goods according to treaty obligations, mediated between Indians and whites, and tried to influence the tribes to accommodate themselves to Government policies. Some of the officials, such as Tom Fitzpatrick and "Kit" Carson, were men of ability and dedication. Many, however, appointed as a reward for political services, were not only innocent of knowledge and understanding of Indians but frequently incompetent and dishonest as well.

Only dimly did the Indians perceive the implications of the first, seemingly harmless, requests of the Government's emissaries. The latter asked the guarantee of safe passage to emigrants and withdrawal from the trails. In return, once a year the Great Father in Washington would send generous presents. Most tribes, still regarded under U.S. law as "domestic dependent nations," signed treaties committing the exchange of promises to paper, and they came at specified times to centrally located agencies to receive presents from an agent appointed for the purpose. The Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851), with the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, and other tribes of the northern Plains, and the Treaty of Fort Atkinson (1853), with the Kiowas and Comanches of the southern Plains, set the pattern for others that followed. The Upper Platte and Upper Arkansas Agencies represented the tentative and rather informal beginnings of management institutions that in four decades would bend the western tribes to the Government's will.

The treaty system contained serious flaws that doomed it as an instrument for regulating relations between the two races. The signatory chiefs seldom represented all the groups whose interests were affected and could not enforce compliance by those they did represent. The white emissaries did represent the United States, but no less than the chiefs could they compel emigrants and settlers to respect the pacts. Moreover, because of cultural and language barriers, the two sides usually had sharply different under standings of what had been agreed upon. Sometimes, one or both sides lacked any serious intention to abide by a compact anyway.

|

| Buffalo were vital to the way of life of the Plains indians. After white hunters slaughtered the animals, troops forced the Indians onto reservations. "Indians Hunting the Bison," Charles Vogel lithograph from Karl Bodmer sketch. (Library of Congress) |

And even the best of faith yielded to tensions. The Indian saw his buffalo and other game slaughtered, his timber cut, his patterns of seasonal migration disturbed, and in places ranges that had been held and cherished for generations appropriated—all by interlopers who also offered tempting targets to a people who set high value on distinction in warfare. The whites, on the other hand, saw the Indian as the possessor of an empire rich in natural resources that he had no means or ability of exploiting and that "natural law" commanded the "higher" civilization to exploit. Many whites saw him, too, as a savage who slaughtered their fellow citizens for mere plunder and the gratification of blood-lust.

Inevitably, friction occurred—along the Oregon, Santa Fe, and Southern Transcontinental Trails; on the expanding Texas frontier and the static New Mexico frontier; and in California and Oregon, where miners and settlers dispossessed the aboriginal occupants of lands coveted for mining or agriculture. For many of the tribes, the decade of the 1850's brought intermittent warfare with the soldiers, whose forts spread in increasing numbers.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/intro1.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005