.gif)

MENU

Design Ethic Origins

(1916-1927)

Design Policy & Process

(1916-1927)

Western Field Office

(1927-1932)

Decade of Expansion

(1933-1942)

|

Presenting Nature:

The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916-1942 |

|

VII. A NEW DEAL FOR STATE PARKS, 1933 — 1942 (continued)

STATE PARK EMERGENCY CONSERVATION WORK (continued)

HERBERT MAIER'S INFLUENCE

Perhaps the most successful of the regions from the viewpoint of consistent, imaginative, and successful application of national park principles and practices was ECW District III, which later became Region Seven and was eventually folded into the National Park Service's Southwest Region. Located first in Denver and then in Oklahoma City, it was headed by Herbert Maier, who also became the director of the Southwest Region in 1937.

Maier, an architect who had worked out numerous solutions for the design of park structures in his work for the American Association of Museums for almost a decade, brought experience, a wealth of sources, and an amazing ability to clearly express the qualities of naturalistic architecture and landscape design. Maier developed an effective process for translating national park principles and practices to the CCC camps responsible for developing state and local parks. This process involved strong design leadership in the central district office and an effective network of state park inspectors who served as liaisons between Maier and the state park authorities on the one hand and Maier and the camp superintendents on the other.

Although an architect and a specialist on park structures, Maier had a fundamental understanding of the landscape principles and practices for park planning that Vint's office had developed in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He passed these principles and practices—whether relating to the sloping and planting of road banks, the construction of guardrails, or the layout of campgrounds—on to his inspectors through photographs, drawings, and simple explanations. The inspectors then translated these to the field, where they conferred with CCC technicians and landscape foremen about ongoing work. Maier himself visited the parks frequently, taking interest in special problems.

Maier was identified as the park service's expert on the principles for designing park structures. He not only drew from his own experience in designing park museums and educational exhibits, but also assimilated the complete range of the Landscape Division's concerns, from road building to campground development. Maier's commissions from the American Association of Museums had brought him in close contact with the Landscape Division as it was formulating an approach to design and a repertoire of major park buildings and with the scientific and educational experts of the national parks as they were developing a coherent program of park interpretation. Maier used the concept of "design by example," circulating ideas and techniques for rustic construction and naturalization work. He had compiled his own Library of Original Sources, which he shared with those working for him. He developed a photographic inspector's handbook with photos that outlined principles to be followed in park work rather than designs to be copied. [8]

Maier's understanding of the relationship of site, setting, and structure matured in the late 1920s through his work at Yellowstone. Probably more than any other park designer, Maier assimilated and perpetuated the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. Although an architect by training and experience, he understood the lessons of Henry Hubbard and readily applied conventions of landscape architecture such as winding walks, native plantings, flagstone terraces, and open foyers to his work. The Yellowstone museums and nature shrines enabled him to develop a common architectural scheme suitable for the park as a whole that could be applied to the specific purposes and characteristics of each individual site. What resulted were interpretive structures, trailside museums, amphitheaters, naturalist residences, and nature shrines that had a common identity but varied in scale, function, materials, and surroundings.

Taking full advantage of the widespread unemployment within the landscape architecture profession, Maier in 1933 assembled an outstanding team of state park inspectors. He drew experts from schools of landscape architecture and public practice. Among his first team of inspectors were landscape architects of considerable experience and acclaim in the profession, including Frank H. Culley and P. H. Elwood, Jr., both former professors at Iowa State; George Nason, who was a Harvard classmate of Daniel Hull and had been superintendent of the city parks in St. Paul, Minnesota, since 1924; and S. B. de Boer of the Denver parks. [9]

Maier assembled drafting expertise in his district office and as a result was able to circulate blueprints of standard designs for cabins, entrance signs, community buildings, and even campground layouts to inspectors and CCC camp technicians and foremen. These drawings were executed by Cecil Doty and show the direct influence of Maier and also park architects such as Arthur Fehr of Bastrop State Park in Texas, whose designs for ECW were considered exemplary. The drawings illustrated representative structures in floor plans, elevations, and details.

Depicting a community building, Sheet 13-A drawn by Doty included the side and front elevations, a cross section of the interior with fireplace, a floor plan, and a detail of fireside seats that doubled as wood boxes. Sheet II-C for weekend cabins carried designs for an L-shaped cabin with an open porch and an octagonal cabin. Both featured immense chimneys that emerged majestically from the rocky uneven ground and Walls battered in a similar exaggerated fashion. The blueprint also carried a detail of a wrought-iron-and glass lantern called a "light bracket" and an interior light fixture made of cattle horns with two hanging lights with wood and iron fittings and designed to hang from an exposed cross beam. Both in their form and in their details, these buildings bore great similarities to the cabins at Bastrop State Park. [10]

|

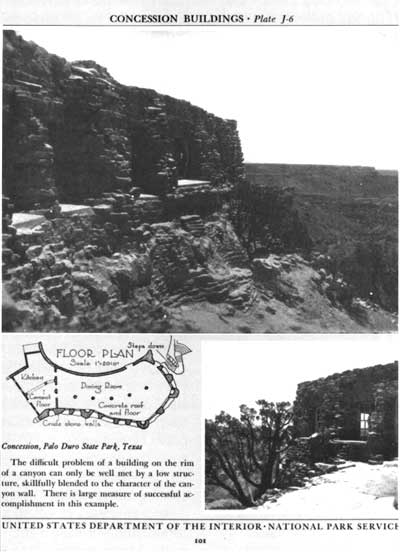

| A rimside location was selected for the lodge at Palo Duro State Park in Texas because of its spectacular view of the canyon. concrete and native stone materials were shaped to fit into and blend with the undulating contours of the canyon wall. Built with a low profile and skillfully modeled in rough stonemasonry, the lodge reflected principles of design followed by Mary colter and Herbert Maier at Grand canyon National Park, while achieving its own unique expression of naturalistic design. (Park Structures and Facilities) |

Because many state parks in the Southwest shared similar dry conditions and an abundant supply of local rock, the same methods of construction and similar designs could be repeated from park to park, with variations allowing for local topography and cultural influences. Standard plans provided several basic designs that could be varied, adapted to local conditions, and elaborated upon. District III's designs called primarily for stone construction that could be adapted to the rocky terrain and natural materials of many western parks. Maier's work on the Yavapai Point Observation Building at Grand Canyon provided him with extensive experience in working with canyonlike terrain and rocky soil. The lodge constructed on the canyon rim at Palo Duro State Park was the direct heir of Maier's Grand Canyon observation station and closely resembled the James House at Carmel by Charles Greene and the Grand Canyon work of Mary Colter.

Maier became the National Park Service's spokesman on the subject of park structures. In 1935, he addressed the conference of state park officials, instructing them in principles of site selection, harmonizing design, and other aspects of construction. Many of Maier's ideas were incorporated in Park Structures and Facilities, edited by Ohio architect Albert H. Good and published by the service several months later as a comprehensive statement of the design principles and practices of the National Park Service at that time.

Today, Maier's speech to the state park officials is an important key to understanding the source of the many ideas that Albert Good put forth and is perhaps the most detailed explanation of park service design. It is an index of practical and aesthetic principles that had evolved out of the formative years of the National Park Service's program of landscape design and Maier's own development as an architect of park structures.

These principles emerged from commitments to providing stewardship for park scenery, preserving parks as inviolate places, and assimilating construction to natural conditions. State park architects, landscape architects, and inspectors in Maier's ECW district were the direct heirs of these principles and played an important role in perpetuating them in state park development. The principles were open-ended, fostered creative expression, and allowed for great variation and diversity based on each park's unique cultural and natural history. They allowed for designs that were unique, yet unified by principle. The idea of an open-ended process based on principle rather than architectural prototype was itself central to the landscape architect's method inherited from Repton and Downing. Park design therefore encouraged experimentation, innovation, and refinement, and, above all, a steadfast search for sensible, simple, and pragmatic solutions that followed function on the one hand and nature on the other.

These principles explain the strength of national park design and the success of the nationwide development of state parks through the leadership of the National Park Service. When it came to state park development, however, the principles were a point of departure for a full flowering of expression that Arno B. Cammerer, then director of the park service, praised in his opening words to Park Structures and Facilities. One of the greatest fears shared by Maier, Wirth, Evison, and other administrators of ECW in state parks was the threat of standardization—that park structures in state parks would be copies of national park structures and that park structures nationwide would look alike. National park designers had used native local building materials and adapted indigenous and frontier forms and construction methods to diversify structures from park to park. The fundamental philosophy and versatility of the principles resulted in vastly different results. Herein lay the strength and unity of New Deal park development, particularly for state parks. By 1935, as Park Structures and Facilities would demonstrate, great vigor and variety abounded in state park work.

While national park design had originated primarily in the West, in mountainous and forested areas in the Rockies, Sierras, and Cascades, the state parks spanned a greater variety of topography, climate, and native character. The true test of the park service's design principles lay in their applications to the varied environmental conditions and recreational uses of state parks. Maier pointed out in his speech the "extreme varieties" of wilderness and semiwilderness parks operated by the various states. They ranged from the woods of Maine and Minnesota to the semiarid mesas of the Southwest, from the heavy conifer forests of the Rockies to the dunes of the Gulf coast. This variety made it necessary to first and foremost determine a character appropriate for the park. Maier summarized the National Park Service's principles for the harmonization of park structures. Structures were to be inconspicuous, and their number limited by combining several functions under one roof, if practical. Large numbers of small structures interrupted scenic vistas and views that should remain free of manmade structures. Shelters, so popular in parks, were justifiable only at particular vantage points at the termination of long walks, and, unless needed for fire protection, should not occur on every peak. [11]

Maier began his speech with a philosophical perspective on stewardship of natural areas. His thinking in the 1930s mirrored his thoughts of the mid-1920s when he had just completed the Yosemite Museum. Aside from roads, he believed, park buildings were the "principal offenders in an activity designed to conserve the native character of an area. The concept of "improvement" was an anomaly in park development. The answer to the dilemma for park designers lay in the simple concept of blending, whether in constructing roads, laying out picnic sites, or building structures for use and comfort. The principles of architectural design and landscape architecture offered simple measures for making structures inconspicuous. By following these, park architects and landscape architects could create structures that harmonized with each particular environment and served the demands of visitor use. [12]

Structures could be made inconspicuous in six basic ways: screening, use of indigenous and native materials, adaptation of indigenous or frontier methods of construction, construction of buildings with low silhouettes and horizontal lines, avoidance of right angles and straight lines, and elimination of the lines of demarcation between nature and manmade structures.

Structures were to be located "behind existing plant material or in a secluded nook in the terrain partly screened by some natural feature." If sufficient natural plant material didn't exist at the site otherwise best suited to the building's function, an adequate screen should be planted by repeating the same plant material that existed nearby. It was best, however, to locate and adapt structures so that "planting them out" was unnecessary. A building with a low silhouette in which horizontal lines predominated was easier to screen. [13]

Using indigenous or native materials was the "happiest means of blending the structure with its surroundings" and was the characteristic that popularly defined "rustic architecture." Maier traced this precedent to the frontiersmen, saying, "Whether he set up his abode on the forest, sod, or adobe covered plains, or in a rock-strewn country, he was forced to adopt the natural material immediately at hand, and when the structure was completed it consequently echoed the identical materials and color from its surroundings." [14]

The adaptation of indigenous and frontier construction included the use of primitive tools that led to a "freehand architecture with an absence of rigidly straight lines, and a softening of right angles." This principle had been an important one in designing the patterns of masonry and the character of guardrails, bridges, and culverts of National Park Service roads. It was likewise a principle that Maier had incorporated in his Yellowstone museums. Maier said, "And so we find that construction which is primitive in character blends most readily with primitive surroundings and is thereby less outstanding and has intriguing craftsmanlike appearance." It was this characteristic that linked park structures with the American Arts and Crafts movement and made that period's prototypes inspirational to park designers. Wirth had just authorized a survey of indigenous frontier architecture of America with plans to publish this compilation, making it "available to designers of structures for wilderness areas with a view toward adapting them to modern needs." The intention of the park service was not to restrict modern park buildings to a primitive form of construction but to "forestall a threatened standardization of park architecture throughout the country." [15]

Maier recommended that designers use colors that blended structures with the immediate surroundings. For instance, he suggested that designers choose colors for the exterior of wooden buildings and the wooden portions of buildings that were commonly found immediately around the site of the new structure. Warm browns and driftwood grays were particularly recommended; green was discouraged, being difficult to match with natural greens. Maier recounted that Yosemite designers had attempted several years before to make buildings inconspicuous from Glacier Point by staining them green to blend into the surrounding foliage. This plan was abandoned when they discovered that the roofs in fact "screamed," because the planes of the roofs reflected the light whereas the surrounding foliage absorbed it. They found that brown blended into the color of the ground beyond and was least conspicuous. [16]

Buildings with low silhouettes and horizontal lines were considered the most inconspicuous. Maier recommended a low roof with a pitch of no more than one-third. He felt that in most locations such a roof was adequate to withstand the weight of annual snowfall. Roofs, in his opinion, too often dominated the design of park structures and were conspicuous from long distances. Straight lines and right angles were to be avoided. This could be achieved through architectural details and finishes—for example, by selecting logs that were knotted and by allowing the knots to protrude. Maier's criticism of the gingerbread style lay in its sawn look, the precision of its lines, and its subsequent effect on the architectural features in which it was used. [17]

|

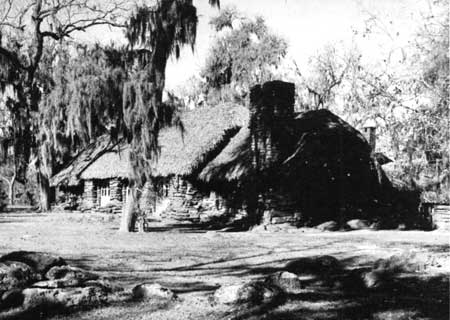

| The concession building at Palmetto State Park was built of reddish brown sandstone, native to the area and reflected Herb Maier's principles of rockwork. Among the special features were the raised terrace with its stonemasonry parapet, the battered stone walls that flared as much as ten feet at the corners of the building, and the massive boulder chimney of stones carefully removed from nature and reassembled at the construction site to appear naturalistic. The camp superintendent wrote, "We are matching rocks in such a manner that they appear to grow out of the ground rather than producing a step effect. To protect the growth of lichen found on the rocks in the flare we are leaving the flare above the ground to be built last . . . I think it worthwhile to protect the beautiful growth which would otherwise be destroyed." (National Archives, Record Group 79) |

Lines of demarcation were to be erased. If possible, structures were to be designed and located so that it was not necessary to plant them out. Vegetation could be introduced along the foundations to obliterate the too-common line of demarcation between building and ground. Rough footings and foundations made of large local boulders at the base of structures to give the impression of natural rock outcroppings was another method for erasing the lines of demarcation. [18]

Buildings were to be in scale with their surroundings. Maier recommended "buildings of a heavy rustic scale (only) for mountainous areas where forests abound." The structural elements, such as logs, timbers, and rocks, were to be considerably over-sized to be in scale with the nearby trees, boulders, and other natural features. Lighter construction was appropriate for less mountainous regions as long as designers steered cleared of "twig" architecture which flourished under the name of "rustic."

Maier's greatest contribution to park design was his mastery of rockwork assimilating both the landscape gardener's emphasis on naturalism and the architect's vision of the construction potential of this material. He recommended the use of naturalistic and natural rockwork to eliminate lines of demarcation. He said,

One of the principal phases of park development which may be an indicator of appreciation of good installations is rockwork in general. The rock selected should first of all be proper in scale, that is the average size of the rocks employed should be sufficiently large to justify the use of masonry. In rockwork it is better, due to the scale of the nearby natural features, to oversize rather than undersize. Whether in retaining walls or in buildings, and bridges, it is usually better to employ rough rockwork or rubble, if properly done, than cut stone, and the weather faces of the rock should, of course, be exposed. Rock should be selected for its color, and for the lichens and mosses that abound on its surface as well as its hardness. [19]

Maier's instructions echoed Henry Hubbard's advice that to be in a "geologically correct" position, rocks were to be placed on their natural beds with strata or bedding planes horizontal. Rocks were never to be placed on end or laid in courses like bricks, and the horizontal joints were to form an irregular pattern. Maier encouraged variety in the size of stones and advised,

In a wall, larger rocks should be used near the base, but this does not mean that smaller ones should be used exclusively in the upper portions, rather a good variety of sizes should be common to the whole surface. I like to see a rock wall splay out near the base and especially at the corners so as to give a feeling of natural outcropping and to prevent a fixed line of demarcation at the ground. The terminating of the top of a wall by creating it with a row of rocks set on end gives a "peanut brittle" effect and is always in bad taste. [20]

Maier stressed the importance of all elevations in park buildings because the public would view and approach these buildings from various directions. Maier was particularly aware of this in his work at Yellowstone and Grand Canyon. At Fishing Bridge in Yellowstone, he ingeniously made the museum building the centerpiece of a larger complex, with a naturalist's cottage to one side, the lake before it, an amphitheater in the woodland behind, and footpaths to parking areas, comfort stations, a nearby concessionaire's development, and trails. The building had several entrances and housed several exhibit rooms.

|

| In keeping with the romantic rustic tradition that A. J. Downing had popularized in the nineteenth century and the American Arts and crafts movement had applauded in the early twentieth century, the roof of the concession building at Palmetto State Park in Texas was thatched with fronds of native palmetto (Sabal minor) to contrast with the hanging Spanish moss that hung from the surrounding elm, pecan, and cottonwoods trees. The roof required 32,000 leaves, many of which were gathered outside the park. Since nine leaves alone weighed ton pounds, the roofing turned out to be quite an undertaking. (National Archives, Record Group 79) |

Maier used landscape techniques and features to blend museum buildings and structures with the natural setting they were intended to interpret. He attempted to integrate interior exhibits with exterior areas such as gardens, amphitheaters, viewing terraces, and trails. Uniting viewpoints within and around the building with surrounding scenic vistas demanded a solution that fused both architectural and interpretative considerations. Maier looked to the terrace, rock-edged walks laid out in irregular curves, and screens and displays of native vegetation to unite the indoor and outdoor activities and the principal and auxiliary functions of the museum. At the Fishing Bridge and Old Faithful museums, Maier and the park naturalists worked at incorporating landscape concerns on a small scale in architectural solutions. As a result, the terrace became part of the park designer's repertoire of devices, and the amphitheater was elevated to an architectural form in its own right.

Continued >>>

Top

Top

Last Modified: Mon, Oct 31, 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/mcclelland/mcclelland7a1.htm

![]()