.gif)

MENU

Design Ethic Origins

(1916-1927)

Design Policy & Process

(1916-1927)

Western Field Office

(1927-1932)

Decade of Expansion

(1933-1942)

State Parks

(1933-1942)

|

Presenting Nature:

The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916-1942 |

|

V. A PROCESS OF PARK PLANNING (continued)

FROM DEVELOPMENT OUTLINES TO MASTER PLANS

In 1929, park development plans were made mandatory. The purpose of this change was as follows:

Such a plan will give the general picture of the park showing the circulation system (roads and trails), the communication system (telephone and telegraph), Wilderness areas and Developed areas. More detailed plans of developed areas will be required to properly portray these special features. These plans being general guides will naturally be constantly in a state of development and should be brought up to date and made a matter of record annually. Their success depends upon the proper collaboration of study and effect on the part of the park Superintendent, the Landscape Architect, the Chief Engineer, and the Sanitary Engineer. The resulting plan will not be the work of any one but will include the work of all. Since Park Development is primarily a Landscape development, these plans will be coordinated by the Landscape Division. [3]

By 1929, therefore, the preparation of plans dominated the work of the Landscape Division. In his annual report, Vint described the division's primary purpose as obtaining a "logical well-studied general development plan for each park, which included the control of the location, type of architecture, planting, and grading, in connection with any construction project." The division was involved in all phases of park development from the location of incinerators to the design of fire lookouts. Landscape architects strongly influenced decisions on where park development was to occur by participating in reconnaissance surveys; identifying and calling for the protection of scenic vistas and significant natural features; and reviewing proposals by superintendents, concessionaires, and other divisions. These proposals included the plans for road and trail projects, tourist facilities, museum developments, administrative centers, and maintenance facilities. The division was responsible for developing all architectural and landscape plans for government facilities and all projects involving the Bureau of Public Roads. It was also responsible for coordinating concessionaires' developments with government facilities. [4]

The plans now contained three parts to be developed in sequence over a three-year period. First was the park development outline that listed the various areas of the park and their components. Next was the general plan, a graphic representation of each particular area. Third was the six-year plan, which was a list of the various projects required to complete any portion of the plan. Projects included the construction of new facilities and the removal of obsolete ones.

Superintendents were responsible for the development outline and were asked to include what they needed to properly develop an area over several years, assuming funds were available. The park development outline was intended to be a written statement of all items necessary for the development of the park. Development was classified according to geographical areas and these areas into units according to use. A standard format ensured that the outline for each park covered the same items and gave an overall view of the park's current condition and future needs. [5]

The new format combined the items previously covered under the five-year plan and the road and trail plans. The plan enabled each superintendent to translate his vision for the park's development into written and graphic form, incorporating the interests of the director as well as the specialists in landscape, educational, and engineering matters.

With the outline, the superintendent could schedule construction and improvements progressively over six years, while maintaining a single vision for the interrelationship of various aspects of development. Maps accompanied the outline and needed to be updated annually owing to the steady progress made in the roads and trails. The outline made it possible to orchestrate the essential infrastructure of park development, that is, to coordinate roads and trails with campgrounds and other facilities and to plan utilities to serve the building program. It also provided an opportunity to advance the landscape standpoint in the location of facilities, the protection of scenic and natural features, and the provision of facilities to enjoy the park scenery. Proposals for underground wiring, scenic turnouts and overlooks, and the removal of dilapidated buildings were included alongside proposals to build bridges and comfort stations.

While the plans called for development in keeping with the directive to make parks accessible to the public, they served the corollary directive for landscape protection as well. The plans indicated "the maximum of building development" for the park, and it was intended that "all other regions of the park were to be left undisturbed, other than new trails and a few necessary patrol cabins." [6]

Under the new format, Mount Rainier's plan outlined development in five categories: a general road system, a general trail system, development areas, entrance units, and miscellaneous development. The road and trail systems were divided into units by names and linear miles. Each development area was divided into eight sections: administrative unit, residential unit, utility group, public auto camp, water supply, sewage disposal, garbage disposal, and concessionaire. Under each section there was an item-by-item description of "existing facilities" and "present and future needs." Entrances were simply named for their location, and component features such as entrance arch, comfort stations, storage sheds, checking station, ranger quarters, stable, water fountains, and water system were classified as "existing" or as "present and future needs." Under "miscellaneous developments" were fire-fighting stations that included water-pumping facilities, caches of tools at patrol cabins, and an assortment of equipment in the developed areas. Also listed in this category were road maintenance camps housing about ten men, shelters for trucks and road-clearing equipment, and a 115-mile telephone system that encircled the park and needed overhauling.

Mount Rainier's park road system was designed to connect with state highways at four entrances and to form, with the state roads, a complete circuit that would encircle the park and allow travelers several points of entry. Six areas of development were planned in relation to the interconnecting network of state and park roads. The park road system was divided into units identified by name and distance, for example, the twenty-one-mile Nisqually Road on the south side of the park extended from the park's southwest entrance to Paradise Valley, and the fourteen-mile Yakima Park Road connected with the Naches Pass Highway near the northeast entrance and extended to Yakima Park.

The maps showed the interconnecting system of park roads and their relationship to state highways or roads through adjoining national forests. A description of the construction program for each two-year period followed. The Nisqually Road, which had been reconstructed and surfaced between 1925 and 1927, was to be paved during the 1928 to 1930 construction program. The one-way road to Ricksecker Point, which was one of the park's most scenic stretches of road and had been closed to traffic in 1922 because of heavy landslides was to be reconstructed and surfaced. The scenic and congested Narada switchback was to be reconstructed and surfaced, and three concrete bridges were to replace wooden ones. While improvements were being made on the park's most traveled route from the southwest entrance to Paradise Valley, work was to begin on the West Side Road and the Yakima Park Road to the east. As part of the third construction program from 1931 to 1933, the twenty-five-mile Stevens Canyon Highway was to be constructed, creating a link between the Nisqually Road to the west and the Naches Pass and Yakima Park roads to the east. This would make it possible for motorists to enter the park from state highways to the east, northwest, southwest, and southeast and travel in a circular manner around the park.

Not only did the park outline call for the construction of buildings and utilities, but it also included items related to landscape protection and harmonization: small parking areas accommodating five to fifteen cars were to be constructed at points of scenic interest along all roads, and guardrails, retaining walls, and roadside slopes were to be constructed to National Park Service standards. Natural features, springs, and trees were to be conserved and protected during construction.

The trail system envisioned for Mount Rainier consisted of one main loop called the Wonderland Trail, which encircled the mountain, and various trails and footpaths connecting the loop with important scenic features and areas. In the mid-1920s, the park's trail system had twenty-five different units covering a total of 241 miles. Many of these had been constructed hurriedly to open up fire patrol routes; to be safe for visitors or for mounted patrols on horseback, they needed to be relocated and improved. Additional trails were needed "to open up important scenic and patrol routes" as roads were constructed and automobile camps developed. The funding for trails included the construction of fourteen patrol cabins on the Wonderland Trail and other trails.

Of the six development areas proposed for the park, only two had begun to take form: Longmire Springs, a mountain resort predating park acquisition on the south side of the park, and Paradise Valley, also on the south side of the park, where a lodge had opened in 1917 and which was envisioned as a center for mountaineering and winter sports. The remaining four areas—Yakima Park, Spray Park, Ohanapecosh Hot Springs, and Sunset Park—were to be developed with government buildings for administrative purposes, free public auto camps, hotels, pay camps, and other concessionary facilities. Of the new areas proposed, Yakima Park received the greatest attention in the years 1929 to 1932. A similar development—to help relieve the crowding at Paradise and open up views of considerable grandeur and access by trails to remote areas of the park—was planned for Spray Park on the western side of the mountain. Dependent on the construction of the West Side Road, it never materialized and was dropped from the plans in the early 1930s. [7]

|

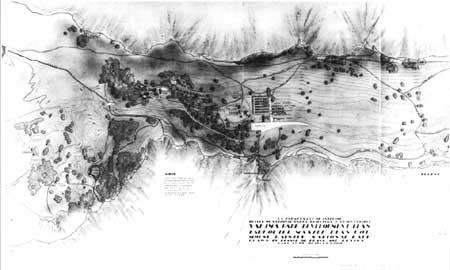

| Master Plan for the Yakima Park Development Area, Mount Rainier National Park, 1933, shows the concentration of buildings around a village plaza and the layout of spur roads and trails that led to outlying scenic overlooks, picnic areas, special natural features, the power station, and a reservoir. (National Archives, Record Group 79) |

Many improvements were proposed for Longmire Springs. A larger administration building, a new comfort station, an assembly hall, a museum building, post office, service buildings, and a one-mile system of underground wiring for telephone and electricity were needed for administrative purposes. Additional housing, a community garage, a variety of work and repair shops, a stable, a general warehouse, and several sheds for equipment were also required. The public auto campground needed to be enlarged, and a variety of buildings, including four comfort stations, a bathhouse and laundry, and a community house were needed. Picnic grounds were also needed. The government facilities relied upon the concessionaire's water system, and designers therefore proposed an independent water system that could accommodate present and future growth. A sewage disposal plant was proposed to replace a primitive system that was both inadequate and unhealthy. An incinerator to dispose of garbage and can-crushing facilities were also needed. Although the concessionaire's facilities were substantial, improvements and additions were proposed.

The construction of the Yakima Park Road was intended to make Yakima Park, a scenic subalpine plateau in the northeast section of the park, accessible to visitors during the summer months. The land was completely undeveloped in 1926 and was one of the first areas to be designed through the advance planning process. The plan called for the following administrative and residential facilities: a two-story administration building measuring twenty-four feet by forty-eight feet to serve as the district ranger headquarters, information office, and living quarters for four rangers; a public comfort station; a branch museum building; and one mile of underground and electric light wiring. Utilities required were an equipment shed, twenty by sixty feet, a bunk and mess house, and a stable for four horses. The auto camp was to serve at least one thousand cars and required six comfort stations, one combination bathhouse and laundry, one community building, a water system with pipes, and about fifty water faucets. In addition to a water system, a sewage disposal plant and garbage disposal plant were needed for government use. The concessionaire was allowed a large hotel accommodating at least five hundred people, staff dormitories, a guide and hiking building, a camp service building with a lunch counter and store, bathhouse, repair and workshops, a stable for thirty horses, and a hydroelectric plant.

Continued >>>

Top

Top

Last Modified: Mon, Oct 31, 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/mcclelland/mcclelland5a.htm

![]()