|

Lake Roosevelt

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 6:

Family Vacation Lake: Recreation Planning and Management (continued)

Recreation Management at LARO, 1966-1974

Park Service Regional Office and LARO staff prepared a new Master Plan for LARO in 1968. Like previous plans, it analyzed LARO's present and future needs and drew up general plans for development. The Superintendent prioritized the development projects, and the Regional Office assigned each proposal a regional priority. The Washington Office then consolidated the regional programs based on the nationwide needs of the Park Service. If Congress did not approve the funding request, then the programs were altered to fit available funds. The passage of the National Environmental Policy Act in 1970 led to greatly increased opportunities and requirements for public involvement in recreation planning. [64]

| |

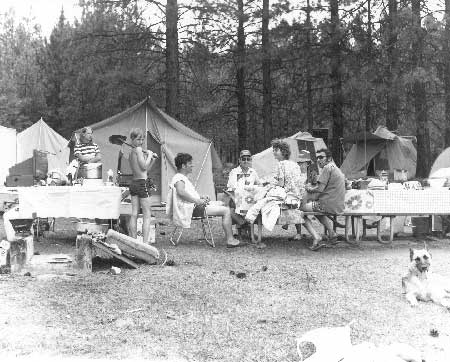

| Camping at Fort Spokane campground, July 1972. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). | |

The Regional Office and even LARO staff still had difficulty singing the praises of the NRA during this period, however, although they did continue to emphasize the significance of the international waterway connecting Coulee Dam, Washington, with Revelstoke, British Columbia. The 1968 draft Master Plan, for example, contained this apologetic statement:

Surrounded as it is by a region outstanding for its lakes, rivers, mountains, forests, and wildlife, Roosevelt Lake suffers by comparison. . . . The lake's generally deep, cold, and murky water, enclosed by usually steep — often eroding — shores, relegates it to second choice after the numerous natural lakes of northeastern Washington and northern Idaho. This body of water is, nevertheless, notable for its length which makes it suitable for long-distance boat touring. [65]

After Mission 66, LARO staff worked with other agencies to accomplish some relatively minor development goals. For example, the Job Corps from Moses Lake installed a concrete launch ramp at Spring Canyon in the late 1960s as part of an expansion program at that site. Group campsites were established at Spring Canyon, Fort Spokane, and Kettle Falls (Locust Grove) in the late 1960s. Apprentices participating in a 1972 Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) training program built a portable entrance station for the Spring Canyon campground using Park Service plans in 1972, and Reclamation built a three-slip floating boathouse to serve both its needs and those of the Park Service. [66]

Ever since the early 1940s and the report of the committee on Problem No. 26, the Park Service had hoped to place all of the former military reservation of Fort Spokane under LARO administration. LARO staff found that the long process of transferring title to the land from the BIA to the Park Service created difficulties in planning for the recreational use of the area. The Solicitor's Office determined that Congressional approval was required for the transfer, and this was accomplished in 1960. The Park Service immediately announced plans to build a visitor center, bathhouse, maintenance shops, warehouses, equipment storage buildings, comfort station, and employee residence on the property, and to improve the road system and utilities. [67]

The construction of the third powerhouse by Reclamation in the late 1960s to increase the power-generating capacity of Grand Coulee Dam directly affected LARO operations. The Park Service had developed a campground and picnic area at North Marina in 1955 that was very popular with locals. It was located not far east of the Reclamation facilities near the dam that included a swimming beach and the Grand Coulee Dam Yacht Club facilities. Construction work for the new power plant required that the North Marina site be used as a fabrication site for heavy equipment. So, the Park Service decided to expand Spring Canyon in order to compensate for the loss of the North Marina developed site. Park Service operations at North Marina terminated in September 1967; North Marina (260 acres) was added to the Reclamation Zone in 1968; the Spring Canyon campground was enlarged in 1969; and plans were made to put in a boat ramp and boat dock. [68]

Another recreation-related development issue that LARO staff dealt with in the late 1960s was the establishment of a housing development known as Seven Bays between Hawk Creek and Miles that had two miles of common boundary with the NRA. LARO staff preferred having a plan in hand for the entire project before it issued permits to the developer, Win Self. LARO gave approval for the corporation to begin work on a beach and a small launch ramp with parking in 1968, with periodic inspections. When it was found that the launch ramp was not feasible in the chosen location, Self expanded his concept to include a concession-operated marina. [69]

| |

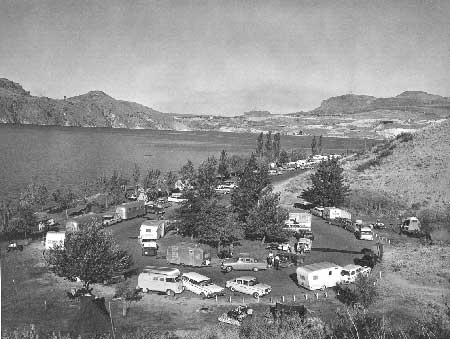

| North Marina Campground, 1962. Visitation to LARO increased this year because of travelers to the 1962 World's Fair. This campground was very popular until it closed in 1967 because Reclamation needed the site as a staging area for construction work. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). | |

Outdoor recreation planning continued on the national level in the 1960s, and some decisions affected the Park Service role in outdoor recreation. In 1958, Congress established the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission. Its final report on the nation's outdoor recreational needs to the year 2000, published in 1962, resulted in a new Department of Interior bureau separate from the Park Service that was charged with overseeing a sweeping program to address the nation's recreation needs. The new Bureau of Outdoor Recreation's mandate essentially took away from the Park Service its responsibility for recreation planning, neglected in recent years, that had been given to it by the Parks, Parkway and Recreation Act of 1936. The 1962 report found that water was a focal point of outdoor recreation for Americans and that swimming, boating, and fishing were among the top ten activities. The Recreation Advisory Council, established in 1962, declared that the primary purpose of national recreation areas was outdoor recreation and that they should be areas "offering a quality of recreation experience which transcends that normally associated with areas provided by state and local governments." [70]

Reclamation contracted with Spokane architect Kenneth Brooks in 1967 to prepare a master environmental plan for the Grand Coulee Dam vicinity. The wide-ranging report included recommendations for sites managed by LARO, such as improvements at Spring Canyon and ferry cruises on Lake Roosevelt. Brooks also proposed fairly extensive recreational development on Banks Lake (including a water-taxi system to take families to campsites); two scenic highways offering vistas of Lake Roosevelt; a Columbia River Valley Parkway between Portland and the Canadian headwaters; and a week-long tour that included Fort Spokane, Grand Coulee Dam, water skiing on Hawk Creek Cove, boating on Lake Roosevelt, a camp-out on Banks Lake, and a helicopter trip to the Hanford facility. LARO Superintendent David Richie found Brooks' ideas exciting and commented in detail on the plan. He mentioned that a new "Grand Coulee Dam national park" could be created that would encompass "the world's greatest dam and its surrounding environment" and could be administered by Reclamation or a new agency. According to historian Paul Pitzer, however, Brooks' elaborate plan "briefly raised eyebrows and then quickly disappeared from view"; the proposed developments were far too extensive to be practical. Most of the changes made as a result of the plan were minor, such as landscaping and beautification projects. [71]

All of the foregoing issues of the 1960s and early 1970s paled before the very complex and contentious issue of tribal rights on the waters of Lake Roosevelt and on the freeboard lands within the two reservations. Tribal jurisdiction over campgrounds within the Indian Zones and hunting, fishing, and boating on Lake Roosevelt came to the forefront during this period as an important issue that needed resolution. [72]

In June 1974, the Solicitor's Office issued an opinion on the boundaries and status of title to lands within the two Indian Zones created by the 1945 Solicitor's Opinion. This opinion had far-reaching implications for LARO, as it held that the two tribes had reserved rights preserved by Congress in the Act of 1940 and that these rights were exclusive of any rights of non-Indians there. Thus, each tribe now had the legal authority to regulate hunting, fishing, and boating by non-Indians in its own Indian Zone. The 1974 Solicitor's Opinion also effectively nullified parts of the 1946 Tri-Party Agreement. [73]

The following month, the Colville Confederated Tribes (CCT) and the Spokane Tribe of Indians (STI) agreed to enforce their fishing ordinances in the existing Indian Zones but to leave regulation of boating, water skiing, and swimming to the Park Service. The enforcement of the fishing regulations proved difficult, however, because the Indian Zones had never been marked by buoys or signs, so the public had difficulty determining their boundaries. The Indian Zones consisted of approximately 45% of the land and water of LARO. In 1982, the CCT made arrangements with the state for reciprocal licensing so that the general public did not have to buy tribal fishing licenses to fish in the waters under their jurisdiction. [74]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

laro/adhi/adhi6e.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2003