|

Lake Roosevelt

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 6:

Family Vacation Lake: Recreation Planning and Management (continued)

The Mission 66 Period, 1956-1966

The Park Service and LARO entered a new era in 1956 with the establishment of the Mission 66 program on the national level. This program resulted from the combination of delayed maintenance of Park Service facilities and increasing visitation to the parks throughout the country. Conrad Wirth, Park Service Director from 1951-1963, conceived of Mission 66 as a ten-year reinvestment and development program, timed to end with the agency's fiftieth anniversary in 1966. Congress responded generously with funding substantially increased over the annual Park Service budget. Wirth was a strong supporter of recreation in the national parks. Mission 66 projects included increased staffing, new interpretive facilities, campgrounds, roads, utilities, administrative and service buildings, restoration of historic buildings, employee residences, comfort stations, marina improvements, and visitor centers. The general emphasis was on improving the quality of the visitor's experience; Mission 66 emphasized use over preservation. [55]

|

In 1966 the Park Service would be celebrating

its fiftieth anniversary. What a God-given target to shoot for! Why

not produce a ten-year program, which would begin in 1956, aimed to

bring every park up to standard by 1966 — and call it MISSION 66? .

. . The entire organization went into action, regional office and park

staffs developing individual project plans and supplying cost estimates

for each park. Morale rose steadily as mouth-watering details were

passed along that old grapevine. In Washington, the park packages were

reviewed every weekend, until the total plan, containing the management

and budget requirements for each of 180 parks, had been completed. And

yet, the final tab seemed far beyond the limits of reality for those who

had been on short rations for so long. The total MISSION 66 program was

projected at $800 million. That the actual expenditure would pass $1

billion was not realized until much later.

-- William C. Everhart, The NPS, 1972 [54] |

Park structures of the early 1950s reflected modern architectural and landscape design and the use of modern construction materials such as concrete, glass, and steel. This type of design for Park Service buildings continued throughout the Mission 66 program. The Washington Office Division of Landscape Architecture commented that each area to be developed at LARO should be designed to have a "first class appearance," noting that "until this is done, Coulee Dam N.R.A. will remain neglected, rundown, and lost in the Master Plan files!" [56] In 1968, LARO staff proposed three architectural themes for the area, ones that were appropriate to the desert character of the southwest shoreline, the wooded northeast shoreline, and the historic features at Fort Spokane. [57]

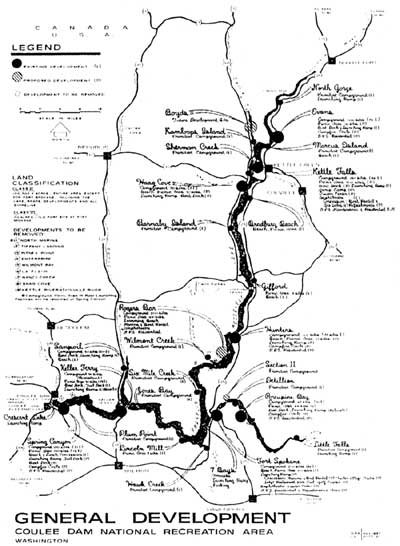

As part of Mission 66 planning, every park prepared a Mission 66 prospectus, with assistance from the Regional Offices. The LARO prospectus, authored by Superintendent Hugh Peyton, emphasized two types of proposed development at LARO. One was the provision of facilities currently needed. The other was a program to set aside and save for future public use the Lake Roosevelt shoreline and recreational resources and to resist summer home sites, individual group development, and other such uses. He proposed many "pioneer" developments with minimum facilities to establish public rights to various sites. The overall program was quite ambitious: 132 new developed areas, varying from the "pioneer" or wayside areas with two table-fireplace units to campgrounds with 120 campsites, with a total of sixteen major areas. By 1963, more than halfway through the Mission 66 decade, LARO's facilities for visitors (not including those provided by concessionaires) consisted of fourteen bathhouses, twelve comfort stations, two picnic shelters, and seventy-six pit toilets. The most popular sites were Coulee Dam, Fort Spokane, Porcupine Bay, Kettle Falls, and Evans. [58]

|

One of the principal reasons for putting

minimum facilities at various spots along the lake in the form of minor

development areas is to "homestead" and keep these areas in public

ownership for future generations and to resist the eternal pressures of

groups and individuals to acquire Government land for private use, which

would exclude practically forever the vacationist who will need this so

desperately in the future. With the completion of MISSION 66 all of

these areas will receive proper attention and they will be preserved for

the use of future generations. The constant increase in the use of

present facilities in the area indicates that there is an urgent need

for the type of recreation which can be afforded by Coulee Dam National

Recreation Area.

-- Hugh Peyton, LARO Superintendent, 1957 [59] |

Peyton promoted LARO in the Mission 66 prospectus as the "Family Vacation Lake." He noted that NRA staff expected a tremendous increase in visitation during the coming decade. Their proposals for Mission 66 involved setting up low-cost minimum facilities to handle present and anticipated future needs. Peyton wrote, "Our area, in effect, is bypassing the normal slow gradual development, and passing from a pioneer stage into complete development." He continued, "We are confident that this quickening course is necessary and we welcome its coming." [60] LARO's Mission 66 prospectus was approved in April 1957. The total cost of proposed physical improvements, including roads, trails, buildings, and utilities, came to an optimistic $2,572,600, about 1/3 of which was earmarked for Fort Spokane. [61]

LARO never was flush with money, however. Even during the Mission 66 period, when Homer Robinson was Superintendent, much of the work was still done on a shoestring with much donated labor and scrounged materials. For example, all the LARO staff, plus Superintendent Robinson's wife, spent several Sundays at Keller Ferry clearing rocks and brush and trees to develop a small recreation area near the ferry landing. The ferryman allowed them to attach a pipe to his garden hose to provide water for the site. Next a pit toilet was built there, and then trees were planted. Sis Robinson felt the improvements were "VERY primitive," and LARO maintenance foreman Don Everts agreed that because little money was available, "we did it ourselves." Everts referred to some of these small campgrounds as "hatched," because he would fly over Lake Roosevelt and map the areas where people were already camping without facilities; the Park Service would then develop them. [62]

| |

| Visitor facilities constructed at Keller Ferry, 1959. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). | |

Mission 66 and its special funding sources represented a turning point for LARO's development. Throughout the Mission 66 period (1956-1966), LARO made great progress in its visitor facilities, although nowhere near the proposed improvements. By 1968, the NRA had thirty campgrounds (nine of which were accessible only by boats), sixteen boat launching ramps, twenty-two fixed docks, and twelve developed swimming beaches (six with lifeguards). Many campgrounds had been expanded, and a few boat launch ramps had been built. Concessions, however, still played only a minor role at LARO. [63]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

laro/adhi/adhi6d.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2003