|

Lake Roosevelt

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 1:

When Rivers Ran Free (continued)

The Secretary of War turned the abandoned post over to the Secretary of the Interior for an Indian School on August 28, 1899. At that time, the federal government had been funding Indian schools for nearly eighty years. A new off-reservation industrial school at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, opened in 1879 and soon became the model for Indian boarding schools. The philosophy moderated ten years later, with increased emphasis on day schools for younger children, boarding schools for intermediate students, and off-reservation industrial schools to carry students through the eighth grade. [31]

The Indian Service saw the abandoned buildings at Fort Spokane as a good site for a boarding school to supplement the day school at Nespelem. The school opened on April 2, 1900, serving up to two hundred Indian children. The underlying philosophy of all Indian schools was the destruction of Indian culture, which, it was believed, would lead to assimilation into American culture. The children at the Fort Spokane school attended classes only half a day, with the remainder of each day devoted to vocational training. The boys practiced farm skills, such as feeding chickens, milking cows, or working in the garden. The girls, on the other hand, learned domestic work such as cooking, laundry, ironing, and making beds in the dormitory. Children who ran away were returned to the school where they spent time in the former military guardhouse as punishment. Enrollment dropped and expenses increased, causing the school to close in 1908. A hospital that followed the school specialized in treating respiratory diseases in children from reservations throughout the West. Again, rising costs forced its closure after just two years. Another hospital operated there from 1918 until 1929, when the facilities were closed permanently. [32]

| |

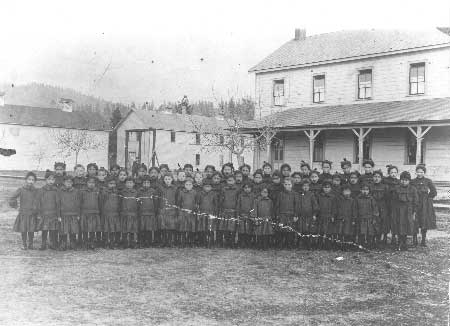

| Group of girls who were students at the Indian School at Fort Spokane, ca. 1903. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 3016). | |

The displacement of Indians continued as more non-native people settled permanently in northeastern Washington. Interest in the mining and agricultural potential of the Colville Reservation led to the cession of the north half in 1891, a move bitterly opposed by Sanpoil and Nespelem tribal members. This agreement allowed 1.5 million acres to return to the public domain for eventual settlement by non-Indians. The north half of the Colville Reservation was opened to mineral entry in 1896, followed two years later by the opening of the south half. This gave non-natives claims on even more Indian land. The final blow came with the allotment of both the Colville and Spokane reservations in the early 1900s. Such division of reservation lands was guided by the General Allotment (Dawes) Act of 1887, under the premise that encouraging farming on individual allotment parcels within the reservations would help break the traditional social order and hasten assimilation. After each family head was given 160 acres and other individuals lesser amounts, the remainder of the reservation was thrown open to settlement by non-Indians. Indians on both reservations took allotments along the rivers wherever there was flat land. This caused a local newspaper to complain in 1914, "The Indians have taken the cream of the reservation. Their allotments cover practically all of the valleys along the streams, including the rich irrigable lands along the west bank of the Columbia." The Spokane Reservation was opened for homesteaders in 1909 and the following year for mineral entry. Settlers began claiming Colville Reservation lands in 1916. [33]

| |

| Indian hospital in former bachelor officers' quarters, Fort Spokane, 1920s. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 2217). | |

Railroads stimulated settlement along their routes in northeastern Washington. The completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad through Spokane and Lincoln counties in the early 1880s brought an influx of new settlers. Later that decade, the Spokane Falls & Northern line initiated service from Spokane Falls to Colville and brought both residents and industries to this region; this line extended to Northport in 1892 and to the border a year later. The railroads not only brought new people but also provided a way for farmers and industries to get their products to market. By 1900, farming was the dominant land use in the Columbia valley, with particular emphasis on orchard crops. While many farmers pumped irrigation water from the Columbia, those associated with the Fruitland Irrigation District used water from the Colville River, which reached their farmlands with an extensive ditch and flume. Grain and livestock came to dominate the more arid lands of Lincoln County. [34]

The perceived potential for these arid lands stimulated investigations into ways to bring water to the Columbia Basin. Two plans were extensively examined, one to develop a gravity plan to bring water from the Pend Oreille River with a dam at Albeni Falls and one to pump water from the Columbia River. The pumping plan prevailed and called for construction of a dam at Grand Coulee and an equalizing reservoir to provide enough water to irrigate 1.2 million acres. This set the stage for a project that changed the face of northeastern Washington and generated ripple effects that reverberate today. [35]

| |

| Town of Peach and some of the orchards that gave the town its name, ca. 1920. Both the town and the trees were flooded by Lake Roosevelt. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 2930). | |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

laro/adhi/adhi1c.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2003