|

Lake Roosevelt

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 1:

When Rivers Ran Free (continued)

Miners initially concentrated on placer gold, found most readily in sand and gravel deposits in rivers and streams. The prospectors included many Chinese, who frequently worked claims abandoned by their Euroamerican counterparts. A store at Hawk Creek served nearly three hundred Chinese miners working along the river in the late 1870s. Within a few years, the region's Chinese population had grown to approximately one thousand, making more Chinese than white miners along the Upper Columbia. Their numbers dropped, however, as ore deposits decreased and restrictive laws increased. Some returned to China, while others moved to cities for more lucrative work. [21]

| |

| Mining with a sluice box on the Columbia River, 1890s. Photo courtesy of U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Grand Coulee (USBR Archives 908). | |

The mining boom stimulated the growth of agriculture in the region, particularly in the relatively temperate Colville Valley and in the Columbia Valley south of Fort Colvile. Some former HBC employees had taken up farms in this area, starting as early as the 1830s. They supplied food to the fur trade post and later sold agricultural products to the Army and the burgeoning mining population. In addition to the non-Indian farmers, many Colville and some Lakes Indians farmed their traditional lands in the same area. Some continued their semi-nomadic lifestyle at least part of the year. After planting their crops in the spring, they left for their annual cycle of root gathering and fishing. They then returned to their farms in the fall to harvest crops from their untended fields. Indian agent William P. Winans reported that Indians apparently had more success with garden produce than their non-Indian neighbors due to their warmer growing season at the mouth of the Colville River. "I purchased early in July peas, carrots, beets, onions, cabbages, etc.," he wrote, noting that the Indians "are the only ones that have so far successfully cultivated the tomato, the frosts not troubling them as early as those living further up the valley." [22]

Winans was one of a series of Indian agents who dealt with tribes on behalf of the government during this period. Pinkney Lugenbeel had taken on these duties as early as 1861 in connection with his role at Fort Colville. From 1868-1872, the agent was known as the "farmer-in-charge." His duties included encouraging agriculture in the belief that this would help Indians adapt to white culture. Once native people had settled on individual farms, the government planned to open "excess" lands for non-Indian settlement. [23]

By the early 1870s, Indians realized that it was in their interests to secure a reservation since settlers were taking over much of their traditional lands. The government also believed that it was important to move non-treaty Indians to reservations to finally establish which lands were available for white settlement. Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Washington Territory, T. J. McKenny, recommended that the Colville reservation be an area at least forty miles square that included "the old fisheries south and west of the Hudson's Bay trading post." An Executive Order of April 9, 1872, set aside a reservation that included roughly all of northeastern Washington east of the Columbia River and north of the Spokane River, to accommodate Colville and neighboring tribes. [24]

Agent Winans had a different view, however. As a merchant, he perceived development of the Colville area proceeding more smoothly without Indians; this was a view probably shared by many settlers. Winans wrote to his Congressional delegate and recommended that the reservation be moved to the other side of the Columbia River. The Executive Order of July 2, 1872, accomplished his goal with a 2.8 million-acre reservation bounded on the north by Canada, on the west by the Okanogan River, and on the south and east by the Columbia River. Winans saw the proposition as a win-win situation. The earlier reservation was too small for the large Indian population, he claimed, and did not have enough grazing land for their herds. Further, since most of the good agricultural land was already taken by non-Indians, they would have to move before Indians could have the land. [25]

Colville leaders appealed to President Ulysses S. Grant in the strongest terms, saying that this move would deprive them not only of their farms and hay lands, but also their homes, villages, and mission that were all east of the Columbia. They feared being unable to rebuild if forced to move and worried that "the little progress in civilization we made already will be lost." [26] Special Commissioner John P. C. Shanks, assigned to investigate Indian affairs, reported on conditions in the Colville area in 1873. He noted the duplicity of Agent Winans and called the forced move to the new reservation "expensive, troublesome, dishonorable, and wicked." [27] Ultimately, the effort was futile and most Indians had moved to the reservation by the 1880s. The government reached agreement to move the Moses band of Columbia Indians to the reservation in 1883, followed by Joseph's band of Nez Perce two years later. [28]

The Spokane Indians were not happy with this new reservation, however, since the area north of the Columbia was outside their traditional territory. In addition, most Spokane tribal members considered themselves Protestants, but most Indians on the newly formed Colville Reservation were Catholics. They refused to move, claiming that they would starve in the barren land north of the river. Agent John Simms advised the government that these people would not move voluntarily and warned of potential war if they were forced off their lands. Members of the Lower Spokanes negotiated with Col. E. C. Watkins, an Indian Inspector, in August 1877, with the result that land known as "Lot's Reservation" was set aside for their use. They pushed for additional land to accommodate the whole tribe and achieved some boundary adjustments reflected in the Executive Order of January 18, 1881. This officially established the Spokane Reservation with 154,898 acres. The Middle and Upper Spokanes did not want to move to the new lands until they had been compensated for the loss of their traditional lands, by then occupied by the rapidly growing city of Spokane Falls. In an agreement signed in March 1887, tribal members ceded their lands and agreed to move in return for approximately $127,000 for building materials, cattle, seeds, and farm equipment. Most of the Upper Spokanes moved to the Coeur d'Alene Reservation in Idaho while the Middle Spokanes moved to the Spokane Reservation. [29]

| |

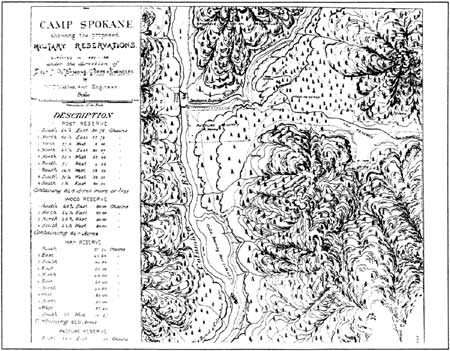

| Map of Camp Spokane and vicinity, 1880-1881. (Frame 774, RG 049, WSA-ERB, Cheney.) | |

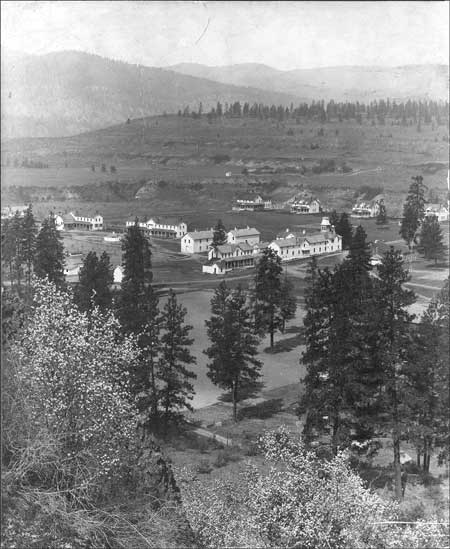

General Oliver O. Howard, commander of the Department of the Columbia, approved the site for a new military post, at the confluence of the Columbia and Spokane rivers, in 1880. The advantages of the new location included proximity to the new Northern Pacific Railroad line at Spokane Falls to facilitate rapid movement of troops if needed. Howard relocated a garrison of the 2nd Infantry from Camp Chelan to Camp Spokane in October 1880, and they were joined over the next five years by troops from Fort Colville. An Executive Order in January 1882 made the camp a military reservation, and the name changed to Fort Spokane a month later. The original tents and log cabins were replaced eventually with forty-five buildings suitable for a permanent six-company post. The fort's layout featured a large parade ground surrounded by frame and brick buildings. This was a time of relative peace in the Inland Northwest, however, and the troops at Fort Spokane saw little action aside from routine drills, parades, and patrol duty. In an effort at efficiency and economy, the Army decided to consolidate Fort Spokane with two other regional posts, with the new post to be built near the city of Spokane. Before this change was completed, troops left Fort Spokane for the last time in April 1898, heading to the Spanish American War. The Army did not reoccupy the post after this date. [30]

| |

| View of Fort Spokane from the south, ca. 1903. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 3014). | |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

laro/adhi/adhi1b.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2003