HARD DRIVE TO THE KLONDIKE:

PROMOTING SEATTLE DURING THE GOLD RUSH

A Historic Resource Study

for the Seattle Unit of the

Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park

CHAPTER THREE

Reaping the Profits of the Klondike Trade

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition

In May of 1898, The New York Times announced that the Klondike excitement was "fizzling out." [88] Although this assertion proved to be premature, it signaled that the frenetic pace of the stampede was slowing down and that the media's interest was waning. The outbreak of the Spanish American War in April provided a new arena for the nation's reporters, and that topic pushed the Klondike out of the headlines. [89] By late 1898, the rush to the Klondike had subsided considerably. The following year new gold discoveries in Nome deflected attention from the Yukon to western Alaska, and Seattle continued to function as an outfitting center. [90] In April and May of 1900, approximately 8,000 gold seekers passed through Seattle on their way to Nome. [91] During the early twentieth century, miners continued to travel through Seattle on their way to subsequent gold rushes to Fairbanks, Kantishna, Iditarod, Ruby, Chisana, and Livengood. [92]

The trade to the Far North never regained the excitement of the Klondike Gold Rush. Seattle, however, retained its dominant connection to this region -- and it continued to supply Alaska with lumber, coal, food, clothing, and other goods. By 1900, Alaska's population had reached 63,592 residents, many of whom remained "heavily dependent" on Seattle for trade. [93] This link between Seattle and the Far North endured throughout the twentieth century.

To celebrate its ties to the Far North and to commemorate the Klondike Gold Rush, Seattle hosted the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1909. This world's fair represented a "coming-of-age party" for the city, signaling the end of its pioneer era. In 1905, Portland similarly hosted the Lewis and Clark Exposition to commemorate the centennial of the 1805 expedition to the Pacific. Its fair attracted three million visitors -- a point Seattle boosters noted with interest. Four years later, Seattle's exposition drew nearly four million people, focusing national attention on the city and the region. [94]

Organizers wanted to hold the event in 1907, to honor the 10-year anniversary of the Klondike Gold Rush. Jamestown, Virginia, however, also planned to celebration its 300-year anniversary with a fair in 1907. In any case, the Panic of 1907, a nationwide depression that slowed the economy in Seattle, would have reduced the scale of festivities and the visitation -- so it was a fortuitous turn of events that delayed the exposition until June of 1909. [95] On that date, President William H. Taft at the national capitol pressed the gold nugget Alaska key, setting the fair's operations in motion. Railroad magnate James J. Hill greeted 80,000 spectators in the commencement celebration, which included a parade in downtown Seattle. [96]

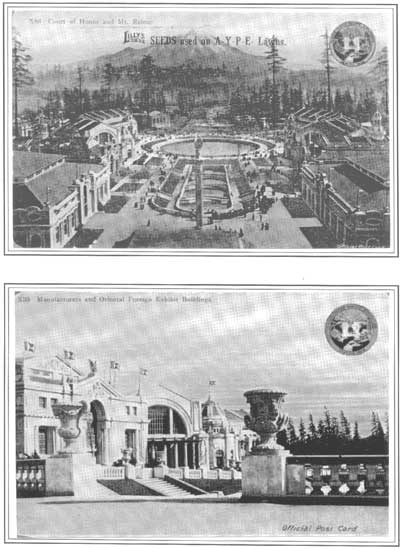

The Olmsted Brothers served as landscape architects of the fair, while John Galen Howard became its principal architect. Held on the grounds of the University of Washington campus, the exposition featured pools, fountains, gardens, and statuary that opened on a vista of Mount Rainier. A variety of ornate buildings designed in the French Renaissance style housed exhibits from all over the world. [97]

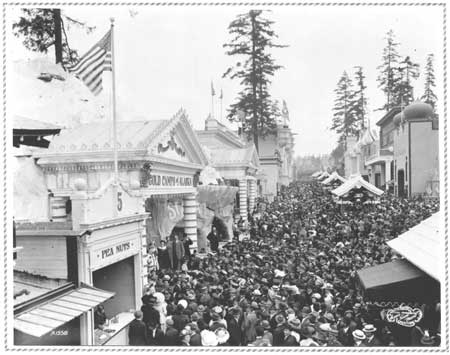

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition included an amusement park

called the "Paystreak;" a term for the richest deposit of gold in placer mining.

The Paystreak featured an attraction called "Gold Camps of Alaska."

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, University of Washington)

The exposition included an amusement park with carnival rides and other entertainment. It was called the "Paystreak" -- a term for the richest deposit of gold in a placer claim and an allusion to the importance of gold mining to Seattle. The Paystreak featured an attraction called "Gold Camps of Alaska" as well as an Eskimo village. Additional references to the Far North at the exposition included a large gold nugget, on display from the Yukon. Especially visible was the Alaska monument, a column measuring 80 feet high. Covered in pieces of gold from Alaska and the Yukon, it stood in front of the U.S. Government Building, reminding visitors of the ties between Seattle and the Far North. [98]

While reflecting on the past, the exposition also looked to the future -- and organizers hoped to boost interest in Seattle and the Northwest. "This summer's show is essentially a bid to settlers," noted one reporter, "and an advertisement for Eastern capital to come West and help develop the natural resources which offer wealth on every hand." The exposition featured numerous promotional booths from cities such as Tacoma and Yakima. Washington and other western states financed construction of buildings that featured their products and resources. The exposition also celebrated the Pacific Rim, promoting increased trade with Asia. Japan, China, Hawaii, and the Philippines provided exhibits, and a Japanese battleship docked in Seattle's port in honor of the fair. [99]

Seattle merchants and residents hoped that the economy would boom as a result of the Alaska-Yukon Exposition. Irene and Zacharias Woodson, for example, expected the demand for housing to expand in the summer of 1909. This African-American couple operated a cigar store and rooming houses in downtown Seattle, using the profits to purchase new properties. The Woodson Apartments, constructed in 1908 at 1820 24th Avenue, represented these hopes. [100]

The exposition ended in October of 1909, marking the end of an era. Although most of the infrastructure was removed, several buildings remained, including Cunningham and Architecture halls. Today, they stand on the University of Washington campus as testaments to a significant point in Seattle's history.

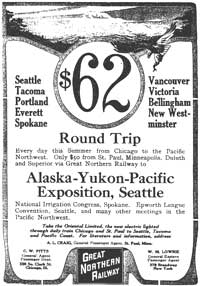

The Great Northern Railway advertised the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific

Exposition.

(Courtesy Special Collections Division, University of Washington)

Another legacy of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was that it strengthened the link between Seattle and the Far North in the public mind. Seattle had developed a significant connection to Alaska before the Klondike Gold Rush, and promoters such as Erastus Brainerd had used the stampede as an occasion to publicize that tie in the late 1890s. The exposition similarly advertised it in 1909. As historian Clarence B. Bagley summarized, the fair successfully met the city's objectives: it demonstrated "the enormous value of Alaska to the United States and the greatness of its entry port, Seattle. The city's guests left the fair with the knowledge that Alaska was a golden possession and Seattle a growing metropolis." [101]

It is difficult to measure the precise impact of the fair and the worldwide exposure it provided to Seattle. As noted, by 1910, the city's population had jumped to 237,194 residents. According to MacDonald, however, the dramatic growth in the city's economy occurred before 1910. After that point, the city "settled down to the moderate growth of the region," abandoning the "independent, enthusiastic" mood of the previous era. [102] Seattle's foreign trade had grown rapidly during the first decade of the twentieth century, but for all the hopes of exposition promoters, there was no immediate increase in trade with Asia after the fair. [103] Not until the late twentieth century would Seattle again experience the vibrance and energy exhibited during the gold-rush era.

Post Cards from the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

(Courtesy Office of Urban Conservation, Seattle)

End of Chapter Three