Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

The Rising Comanche Tide Between 1760, the year an anonymous imperial strategist recommended the creation of a separate northern viceroyalty in New Spain, and 1776, the year the crown set in operation the unified General Command of the Provincias Internas, almost a viceroyalty, the indios bárbaros ran wild.

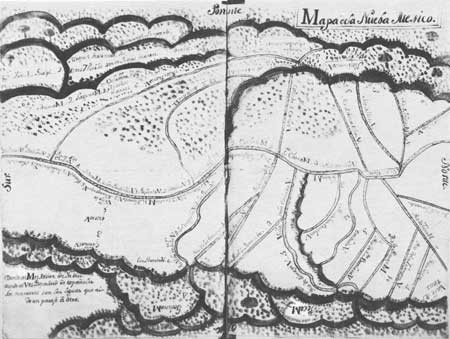

At Pecos, trade with Apaches declined as Comanche hostility heightened. Although Jicarillas and their allies continued to live in and around the mountains north and east from Santa Fe and Pecos, no one mentioned Pecos "fairs." The pueblo's population fell from 344 to 269. The Franciscans neglected it. No longer did the friars bother to enter in the book of burials the Pecos dead. From time to time, however, they showed up in the governor's routine body counts. On January 13, 1772, for example, "9 Comanches killed two Indians of the Pueblo of Pecos who went out to look for their oxen." That was not the whole story, but it was a telling part of it. [42] Gov. Francisco Marín del Valle was an adherent of the eye-for-an-eye school, or better, many heathen eyes for one Spanish eye. During his administration and those of his two short-term successors, violence begot violence. To avenge the spectacle of Taos dancing with two dozen Comanche scalps before their very eyes, the Comanches rallied a huge war party and descended on the Taos Valley in August 1760. Their seige and plunder of the Villalpando house, where dozens of Spanish men, women, and children perished or were carried off alive, so impressed Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco that he related it in the legend of one of his maps nineteen years later. Although Marín's retaliation failed, Gov. Manuel Portillo Urrisola enticed the Comanches to Taos late in 1761 and succeeded in killing "more than four hundred." By "this glorious victory," he had hoped to inspire such dread in all heathens that New Mexico would be left in peace. But he was worried. His successor had arrived. This official spoke of summoning the Comanches to talk. Tomás Vélez Cachupín was back. [43] Again Vélez embraced Comanches, sat and smoked with them, and negotiated an exchange of prisoners. He condemned the arrogant Portillo, "who never wished to hear them speak directly to him." But even though don Tomás demonstrated again during his second term, 1762-1767, how Spaniards could reason with Comanches, the man who followed him, for one reason or another, was not up to it. Don Pedro Fermín de Mendinueta, whose eleven-year administration was the longest in New Mexico's history, and probably the bloodiest, never commanded the Comanches' respect the way Vélez Cachupín had. He was always on the defensive. [44]

Mendinueta Vacilla Not that Mendinueta wanted all-out war. He recognized that New Mexico was too weak, almost prostrate. Still, his superiors cried for blood, for the vindication of Spanish arms. Much of the time he spent trying to get the scattered Hispanos to come together in compact defensible communities, or placitas. Never able to win a great enough victory to dictate lasting peace, the governor vacillated as a matter of policy. Writing of the Comanches in 1771, he admitted as much.

If the viceroy had any better policy to suggest, Governor Mendinueta was ready to listen. [45]

Mostly War at Pecos For Pecos, traditional target of the Comanches, the now-peace-now-war regime of Fermín de Mendinueta meant mostly war. This was not war in the conventional sense, nor was there any reliable pattern to it. One time the attackers came in the dead of winter, hundreds strong, hurling themselves at the pueblo, and the next in spring or summer when only a dozen or so lay in ambush for workers in the fields, wood cutters, or hunters. The irregularity of this war, the not knowing, must have taken as great a psychological toll as it did physical. Like the serial stories filed by a war correspondent, Mendinueta's letters to the viceroy make up a chronicle. March 10, 1769: a Pecos reports fresh Comanche tracks some leagues from the pueblo. They lead in the opposite direction. Nevertheless, Alcalde mayor Tomás de Sena sends scouts and waits up at Pecos all night. When the sun rises next morning, the scouts still have not returned. Believing that the Comanches must have been after Apaches, the people let out their livestock without telling Sena.

The Pecos blamed this attack on their war captain, who had given the wrong location of the tracks. Mendinueta complained that he often received misinformation. No one saw the enemy, but everyone reported false alarms. [46] Early on a winter morning in December 1770, two Pecos venture out of their pueblo. A short distance down the trail some thirty Comanches jump them. It is over in an instant. The raiders also recapture sixteen horses stolen from them by Apaches who had come in close to Pecos. On April 5, 1771, forty Comanches assail the pueblo but are beaten off. The following month the alcalde mayor, probably Vicente Armijo, catches up with five Comanches rustling horses and kills all five with no casualty among the Indians who accompanied him. Again Comanches attack Pecos on September 5. Again they are repulsed. Later in the month, the governor sends the lieutenant of the Santa Fe presidio and two squads of soldiers. One squad escorts the Pecos to their fields to harvest and bring in their wheat. Despite the Comanches, who show themselves and shoot a few arrows from a distance, the soldiers, the Pecos, and their alcalde mayor fall back in good order with wheat and livestock. This time, the Comanches ride off. A month later they are back, an estimated five hundred strong. A smoke signal sent up by scouts alerts the Pecos and the squad of soldiers. The enemy, dismounted, tries to force one of the gates. They fail, losing five men killed and many wounded. Not always are the Pecos scouts so effective. Late that same fall, on November 25, five of them sally out of the pueblo at dawn right into an ambush. All die, along with an oxherd. [47] Eye for an Eye The worst war losses suffered by the Pecos during these years occurred in 1774. That spring, forty of them had left their pueblo to join a body of civilians and a soldier escort, bound perhaps on their annual trip to the salines. Because of the Pecos' "extreme want," Governor Mendinueta had granted them permission to hunt buffalo before joining up. But the Comanches took them off guard. Eleven were killed, one captured, and the rest fled, "losing their meager baggage." At three p.m. on August 15, the Pecos out working their milpas looked up to see a hundred Comanches bearing down on them. They scattered, but not in time. Seven men and two women died. Seven others were carried off. [48] This time the punitive expedition came through. The Comanches, reunited, were celebrating. "So many were the tents that they could not make out where they ended." Charging right into them, the Spaniards cut a bloody swath, then formed a square and held off the enemy all day before retiring in order that evening. An ever greater victory followed a month later. Mendinueta, availing himself of the New Mexicans' momentary high spirits, marshaled a force of six hundred soldiers, militia men, and Indians and sent them out under don Carlos Fernández, an aging but thoroughly proven campaigner. Taking another encampment by surprise, the Spanish force killed or captured "more than four hundred individuals," recovered a thousand horses and mules, and eagerly divided among them the tipis and other spoils of the Comanches. [49] Still, these triumphs did not end the war. In the months ahead, Comanches killed two Pecos cutting firewood, three sowing their fields, and one in a skirmish. In all, if the governor's figures are anywhere near accurate, between 1769 and 1775, some fifty Pecos must have died "a manos de los Comanches." No wonder Father Domínguez found them in 1776 cultivating only the fields within shouting distance of the pueblo. No wonder they had only a dozen sorry nags. No wonder they did not go to the river for a swim. [50]

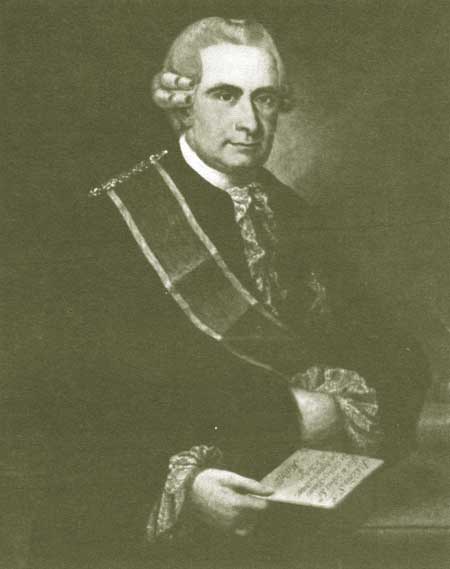

Anza Takes On the Comanches Already a hero, forty-two-year-old Lt. Col. Juan Bautista de Anza rode into Santa Fe late in 1778 with a confidence that bordered on cockiness. Unlike most of his predecessors, he already knew an Apache from a Pueblo. He was a frontiersman, born and reared in the presidios of Sonora. As swaggering as his position demanded, yet brave enough to close in hand-to-hand combat, Anza was a natural leader of fighting men. He had recently sat for a portrait in Mexico City. Feted at the viceroy's palace for opening the overland road from Sonora to Alta California, don Juan was still not too proud to embrace a Navajo or smoke with a Comanche. In that regard, he was every bit the equal of Vargas or Vélez Cachupín. And the time was right. He had just come from a series of meetings in Chihuahua with don Teodoro de Croix, first commandant general of the Provincias Internas. For more than a decade, reform-minded Spanish bureaucrats had been looking at the defense of the northern frontier as a whole. The Marqués de Rubí's inspection of 1766-1768, the resultant Reglamento of 1772 delineating the presidial cordon from the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of California, and the unified general campaigns of the redheaded Irish wild goose, Commandant Inspector Hugo O'Conor, had all followed in rapid succession.

Then, in 1776, don José de Gálvez, formerly the king's archreformer in New Spain, had become minister of the Indies. Within months, his vision of a northern jurisdiction independent of the viceroy and devoted to pacifying, developing, and defending New Spain's most exposed frontier was a reality. The six northern governors, from Texas to California, henceforth would answer to the commandant general. He would communicate directly with the king through Gálvez. Although the main object of the General Command was defense, the royal instructions as usual suggested a more noble purpose: "the conversion of the numerous heathen Indian tribes of northern North America." [51]

One of the decisions confirmed at the Chihuahua meetings would have a direct if belated effect on the Pecos. The Spaniards had resolved to seek peace and alliance with the Comanches against warring Apaches. There were precedents, particularly on the Texas frontier. Anza gave the project highest priority, setting aside temporarily the opening of a road to Sonora, the disrupting of the Gila Apache-Navajo alliance, and other pressing matters. Plainly, the Comanches, epitomized now by a fierce and implacable war leader named Cuerno Verde (Green Horn), were the kingdom's cruelest scourge. Before he parleyed, the new governor had first to show them who he was. That he did in 1779.

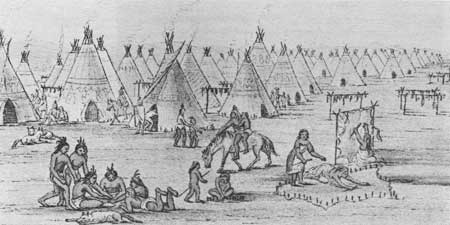

A Signal Victory over Comanches The muster at San Juan was set for mid-August, a time the Comanches might have expected to find them in their fields instead. In all, nearly six hundred men took part, none evidently from the overexposed pueblo of Pecos. Outfitting the dirt-poor militiamen and shaking the column down, Anza led them not by the traditional route east from Taos but north into Colorado and then east. Joined by two hundred Comanche-hating Utes and Apaches, to whom the governor explained his spoils policy of equal shares, the expedition pushed on to and across the Arkansas River. Somewhere north of present-day Pueblo they came upon a large body of Comanches setting up the pole frames of their tipis along Fountain Creek. The scene resembled a Catlin painting. The mountains towered to the west. Anxiously observing the Spaniards "drawn up in a form they had never before seen," the Comanches dropped everything, jumped on their horses and took off. After six or eight miles of pursuit across the grassy plain, the Spaniards and their Indian allies began to catch up. The Comanches wheeled around. Eighteen of the bravest died in the scattered melee. The women and children who ran to their fallen men were captured as were more than five hundred horses. Back at the half-made camp, the spoils were so plentiful that a hundred horses could not carry them all. Learning that this camp was to have been the rendezvous and site of a victory celebration upon the return from New Mexico of Cuerno Verde himself, Anza doubled back, in his words, "to see if fortune would grant me an encounter with him." It did. Somewhere in view of 12,334-foot Greenhorn Mountain, the bold Cuerno Verde, who knew of his people's recent defeat, had the temerity to attack six hundred men with only fifty. Judging from his own diary and the outcome, Anza's tactics were brilliant. Cutting Cuerno Verde and his staff off in an arroyo, he moved in for the kill. "There without other recourse they sprang to the ground and, entrenched behind their horses, made in this manner a defense as brave as it was glorious.... Cuerno Verde perished, with his first-born son, the heir to his command, four of his most famous captains, a medicine man who preached that he was immortal, and ten more." [52] The distinctive headdress of Cuerno Verde with its prominent green horn, and that of his second-in-command Jumping Eagle, were sent by a jubilant Anza to Commandant General Croix as trophies with a pledge to work for even "greater things now and in the future." Although his greatest achievement, the Comanche peace, would take another six years to consummate, this victory over Cuerno Verde had broadcast Anza's fame to every member of the Comanche nation. There would be no shame in coming to terms with this man. At Pecos, meanwhile, other died at their hands. [53] | ||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||