Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Castaño's Desperate Gamble After 1583, when Philip II instructed his viceroy in New Spain to find a man to pacify and settle New Mexico, competition intensified. Hernán Gallegos went to Spain and was politely brushed off. Antonio de Espejo, on his way to the royal court, died at Havana. Then while courtiers and northern frontier magnates contended for the prize, gouging at one another, don Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, a desperate would-be Cortés, gambled everything on getting there first, illegally. The law was explicit. The king had decreed in 1573 a whole set of ordinances designed to regulate expeditions of discovery and settlement. In part they represented the fruition at court of Las Casas' long advocacy of gentle persuasion. Use of the word conquest was banned in favor of pacification. Spaniards were to emphasize the wonderful advantages of Christianity, justice, and security that the natives might gain for themselves by peaceful submission. The horrible penalties of devastation and enslavement for those who refused—spelled out so graphically in the earlier requerimiento—found no place in the new legislation. Settlement was to be made without injury or prejudice to the Indians. [19] The ordinances of 1573 also reflected the financial straits of the Spanish monarchy. To encourage pacification without expense to the crown, the king fell back on granting exorbitant privileges to rich men. The feudal office of adelantado, a sort of lord of the march, as well as great entailed estates, hereditary fortresses, and the right to grant lands and Indian tribute—all this the ordinances held out to the prospective pacifier. Accordingly, as Philip reiterated in 1583, the Spanish colonization of New Mexico must be undertaken "without a thing being expended from my treasury." [20] The hope of such grand concessions—after the fact— must have filled the head of Gaspar Castaño de Sosa. An eager and resourceful frontier veteran, Portuguese by birth, Castaño had joined Luis de Carvajal in "pacifying" Nuevo León, that practically boundless region north of the Río Pánuco, east of Nueva Vizcaya, and extending "clear to La Florida." But it had gone sour. Carvajal's prolonged trial before the Inquisition on charges of being a crypto-Jew tainted his endeavors and his associates. Try as they might, neither he nor his roving minions discovered paying mines. Instead they resorted to wholesale slaving, bringing the added wrath of the viceroy down on Carvajal.

As lieutenant governor of Nuevo León, Castaño de Sosa tried to carry on for his jailed chief. But he had a plan of his own, based, he claimed, on permission implicit in the king's concessions to Carvajal. He would colonize New Mexico himself. To secure the viceroy's concurrence, Castaño dispatched agents to Mexico City. Viceroy Marqués de Villamanrique would have none of it. To the contrary, he cautioned his successor in 1590 to be wary of Castaño and his followers—"outlaws, criminals, and murderers—who practice neither justice nor piety and are raising a rebellion in defiance of God and king. These men invade the interior, seize peaceable Indians, and sell them in Mazapil, Saltillo, Sombrerete, and indeed everywhere in that region." [21] In the heat of June 1590, Capt. Juan Morlete rode into the dusty, unprosperous settlement of Almadén, later Monclova. He handed Castaño orders from the new viceroy, don Luis de Velasco II. They specifically forbade the lieutenant governor to take slaves or to set out for New Mexico without authorization. But Castaño, like Cortés seventy years before, chose to gamble on a dramatic fait accompli and the mercy of a grateful king. He ignored the viceroy. Taking matters wholly unto himself, Gaspar Castaño de Sosa resolved to move the entire settlement of Almadén to New Mexico—men, women, children, servants, dogs, oxen, goats, the lot. They were headed, he assured the nearly two hundred persons, for a land of mines and clothed, town-dwelling people. The king would reward them as he had rewarded the first colonists of New Spain. But they must make haste less some unscrupulous rival steal the march on them. The viceroy's blessings would overtake them en route. A Colony on the Move On Friday, July 27, 1590, the ungainly caravan moved out. A train of cumbrous, creaking two-wheeled ox carts, "una cuadrilla de carretas de Juan Pérez," imposed a crawling pace. These were to be the first wheeled vehicles seen in New Mexico. Strangely enough, the accounts of the expedition mention no friars, or even a secular priest. Perhaps the viceroy was right. Perhaps this lawless band of slavers had no use for missionaries. Castaño may have promised his colonists the benefit of clergy once they were settled in their new homes. Still, it is difficult to imagine a Spanish colony on the move without a priest.

Six weeks later, near today's Ciudad Acuña, they reached the Rio Grande, which they knew as the Río Bravo. Here a slaving party sent out earlier by Castaño rejoined the colony with a catch of some sixty male and female Indians. The lieutenant governor took his share, distributed the others among the soldiers, and made arrangements to ship the chattel south for sale. [22] By late October, after weeks of extreme hardship traversing the dry, broken terrain north of the Rio Grande, the scouts finally found their way down to the brackish water of the Pecos—Castaño's Río Salado—the river that would lead them north to the pueblos. [23] Just above present-day Carlsbad, Castaño convinced himself that he must be approaching the first settlements of clothed Indians. On December 2, he sent out his second-in-command, Maese de campo Cristóbal de Heredia, and at least eleven men-at-arms. They were to capture one or two Indian informants, but were not to enter any native town. Twice in the next two weeks, members of the advance party returned to report and to ask for provisions. Then on December 23, the lieutenant governor spied from a hill a lone figure plodding toward camp behind an exhausted horse without a saddle. Not long after, the rest of Heredia's woebegone troop dragged in. Three were wounded. They had found a pueblo. To a man they described it as large and fortress like. The inhabitants wore clothes of cotton and animal skins. The pueblo sat on a rocky ridge just west of the river the Spaniards were following. Curiously the author of Castaño's "Memoria"—probably secretary Andrés Pérez de Verlanga, if not the lieutenant governor himself—did not give this prominent pueblo a name. It was without a doubt Cicuye. The next year, 1591, after they had been among the Keres people, some of Castaño's soldiers began referring to the big eastern pueblo by an approximation of its Keresan name, the name by which it has been known to outsiders ever since—el pueblo de los Pecos. [24] Castaño's Advance Guard Humiliated Accounts of what happened to Heredia and his worthies at Pecos varied according to who was telling the story. The author of the apologetic Memoria, who endeavored to make Castaño out the hero and faithful vassal of the king, told how the advance party, cold, wet, and hungry, had chanced upon and followed a trail leading up from the river to the pueblo. Numbed by the freezing weather and snow, they sought shelter inside, ignoring the lieutenant governor's order to the contrary.

A clear case of Indian treachery worked on hungry but well-mannered Spaniards—thus the Memoria made it out. Cristóbal Martín, a member of Heredia's party who testified in proceedings against Castaño eight months later, saw the episode somewhat differently. He agreed that the Pecos had received them peacefully, "making the sign of the cross with their fingers," feeding them, and putting them up for the night. Next morning, however, when Heredia asked the Indians for maize "they brought so little that it was nothing. As a result, he ordered some of his men to enter the Indians' houses and remove some maize." At that, the Pecos "rebelled" and drove the Spaniards out of the pueblo. [26] Whatever the circumstances, the Pecos affair put Gaspar Castaño to the test, just as the Tlaxcalans had tested the iron Cortés. If he failed to win the submission of the first pueblo he faced, how could he hope to pacify a kingdom? Without provisions his people would starve. The Memoria records his response. Taking Heredia, twenty able men, seventeen attendants, and a supply of freshly slaughtered ox meat, don Gaspar rode forth to humble the Pecos. In the predawn cold and darkness, the lieutenant governor moved about camp reassuring his men. They must eat hearty and take courage. Because he intended to do the Indians no harm, he was confident that they would receive them well. No man was to make a move on his own. Everyone must obey orders. They were now only a short league from the pueblo. In hopes of finding an Indian who might carry word of the Spaniards peaceful intent, Castaño had Heredia send three men on ahead. Then on the last day of 1590 he and the others, "in formation with banner high," advanced on Pecos.

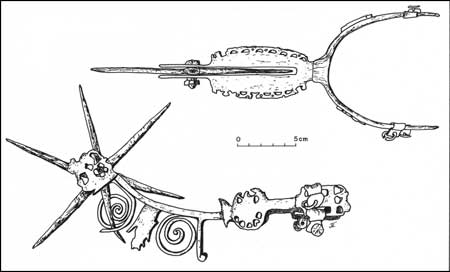

The Pecos obviously meant to fight. Fearing reprisal from the invaders after the Heredia episode, they had thrown up earth parapets atop the pueblo's flat roofs. The other more permanent fortifications, "the low ramparts, earthworks, and barricades which the pueblo has at the places most vital for its defense," puzzled the Spaniards. Later the Indians explained that they were at war with other peoples. Pecos Spurn Castaño's Peace Offer The lieutenant governor tried sign language. When no one ventured out of the fortified pueblo, he approached with Heredia and three others. The Indians shouted their derision. The women continued carrying rocks to the rooftops. The five Spanish horsemen circled the massive, tiered pueblo holding up knives and other gifts. As the clamor increased, the Indians let loose a barrage of arrows and rocks. For five hours, records the Memoria, Castaño sought in vain to placate the Pecos. Back in camp he put everyone on alert and had the horses rounded up. A group rode down and circled the pueblo trying to find out who the "captain" was. They claimed they saw him. Diego de Viruega dismounted and started to climb up a collapsed corner of the pueblo to give gifts to some seemingly less belligerent natives. But they would not let him. When the Pecos captain came over, the Spaniards gave him a knife and other goods, probably tossing them up to him. Still the Indians refused to parley. Castaño was losing patience. Taking his secretary in good Spanish legal fashion, the lieutenant governor started for the pueblo again. This time when the Pecos spurned his peace overtures, he had a writ drawn and witnessed. Then in council he asked his men what course he should take "since these Indians have utterly refused to listen to reason. With one accord they responded, 'Why does Your Grace wait on these dogs?'" The pueblo should be carried by force of arms. But was it not too late in the day, suggested Castaño, "If it is God's will to grant us victory," they reasoned, "there is time to spare." It was about two in the afternoon. On Castaño's orders, Heredia stationed two men on high ground north of the pueblo to report any Indians leaving. Once again the lieutenant governor appealed to the Pecos to lay down their arms. Just then a native woman came out on one of the overhanging corridors and threw ashes at him to the boisterous delight of the crowd. That did it. Castaño shouted orders. All the armed men mounted. Rodríguez Nieto fired a cannon shot over the pueblo and the others discharged a fearful volley from their arquebuses. | ||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||